the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Global inventory of doubly substituted isotopologues of methane (Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2)

Sara M. Defratyka

Julianne M. Fernandez

Getachew A. Adnew

Guannan Dong

Peter M. J. Douglas

Daniel L. Eldridge

Giuseppe Etiope

Thomas Giunta

Mojhgan A. Haghnegahdar

Alexander N. Hristov

Nicole Hultquist

Iñaki Vadillo

Josue Jautzy

Ji-Hyun Kim

Jabrane Labidi

Ellen Lalk

Wil Leavitt

Jiawen Li

Li-Hung Lin

Jiarui Liu

Lucía Ojeda

Shuhei Ono

Jeemin H. Rhim

Thomas Röckmann

Barbara Sherwood Lollar

Malavika Sivan

Jiayang Sun

Gregory T. Ventura

David T. Wang

Edward D. Young

Naizhong Zhang

Tim Arnold

Measurements of methane (CH4) molecules containing two rare isotopes (13CH3D and 12CH2D2), also termed doubly substituted or “clumped” isotopologues, have the potential to provide two additional isotopic dimensions to help investigate the mechanisms underlying global atmospheric trends in CH4. In this work, we summarise the current state of research on doubly substituted CH4 isotopologues, with an emphasis on compiling results of all relevant work. The database comprises 1475 records compiled from the literature published until April 2025 (https://doi.org/10.5285/51ae627da5fb41b8a767ee6c653f83e6, Defratyka et al., 2025). For field samples, 40 % of records were sourced from natural gas reservoirs, while microbial terrestrial (e.g., agriculture, lake, wetland) samples account only for 12.5 %. Lakes samples contribute 75 % to collected microbial terrestrial samples. There is limited or no representation of samples coming from significant microbial CH4 sources to the atmosphere, like wetlands, agricultural practices and landfills. To date, laboratory experiments were mostly focused on microbial (28 % of samples from laboratory experiments) and pyrogenic (15 %) methanogenesis or anaerobic (16 %), and aerobic (8 %) CH4 oxidation, with only single study of photochemical oxidation via OH and Cl, which constitutes 5 % of the laboratory experiments entries. The distinct ranges of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 values measured in these studies suggests their potential to improve our understanding of atmospheric CH4. This work provides an overview of the major gaps in measurements and identifies where further studies should be focussed to enable the highest impact on understanding global CH4.

- Article

(3067 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(321 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Methane's bulk isotopic signatures (in particular δ13C-CH4), have been commonly used to constrain CH4 emissions sources and budget changes (Basu et al., 2022; Lan et al., 2021; Menoud et al., 2022b; Sherwood et al., 2017; Turner et al., 2019). While the observed recent negative trend in δ13C-CH4 with increasing CH4 mole fraction in the atmosphere implies a shift towards increasing microbial sources, the magnitude of this shift is difficult to quantify owing to the uncertainty in the isotopic source terms (Nisbet et al., 2019). Thus, additional independent tracers of CH4 fluxes to the atmosphere would be useful to improve the understanding of global CH4 changes.

The isotopologues 13CH3D and 12CH2D2, referred to as doubly-substituted or “clumped” isotopologues, are thermodynamically more stable than the more abundant singly substituted CH4 (i.e., 13CH4 and 12CH3D). High precision measurements of the ratios of these rarer isotopologues present new tracer capabilities to quantify CH4 sources and sinks (e.g., Douglas et al., 2017; Eiler, 2007; Haghnegahdar et al., 2017; Sivan et al., 2024; Stolper et al., 2014b; Young et al., 2017). The reported values, Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2, represent the measured isotopologue ratios (13CH3D 12CH4 and 12CH2D2 12CH4, respectively) relative to their calculated values that assumes a random distribution of isotopes amongst the CH4 isotopologues. This parameterization proves beneficial, as at thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium, the deviation in these isotopologue ratios from a purely random distribution is solely a function of temperature and it is independent from the bulk isotopic contents. Therefore, measurements of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 can constrain CH4 formation temperatures, if the CH4 has formed in thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium. An important aspect of this parameterization is that at sufficiently high temperatures under thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium (where exchange of isotopes between isotopologues is fully reversible) the doubly substituted isotopic signature tends towards zero. At low temperatures, however, the abundance of clumped isotopes is much higher than expected from random distribution (e.g., Eldridge et al., 2019; Stolper et al., 2014a; Young et al., 2016).

When CH4 is not in thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium, values of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 can reflect other physicochemical processes, such as their formation and consumption reactions (kinetic isotope effects, combinatorial effects, etc.), mixing of different sources, and physical transport processes such as molecular diffusion (e.g., Douglas et al., 2017; Gonzalez et al., 2019; Ono et al., 2014; Röckmann et al., 2016; Stolper et al., 2014b; Wang et al., 2024b; Yeung, 2016; Young, 2019; Young et al., 2017). Therefore, measurements of doubly substituted isotopologues can provide additional analytical dimensions to distinguish between atmospheric sources (e.g., microbial, thermogenic, and abiotic CH4) and sinks (Chung and Arnold, 2021; Douglas et al., 2017; Haghnegahdar et al., 2017; Stolper et al., 2014a; Whitehill et al., 2017; Young, 2019). For example, it is currently understood that the Δ13CH3D of atmospheric CH4 is more sensitive to sources than sinks because it does not appear to be strongly affected by currently known sink reactions, while Δ12CH2D2 is currently understood to be sensitive to both atmospheric CH4 sources and sinks (Chung and Arnold, 2021; Haghnegahdar et al., 2017, 2023, 2024; Sivan et al., 2024; Whitehill et al., 2017). Thus, the atmospheric monitoring of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 has the potential to yield novel and unique insights into the temporal and spatial variations in atmospheric CH4 source and sink reactions.

The first attempt to measure the rare CH4 isotopologues from the ambient air was presented by Mroz et al. (1989), with further methods development refined by Ma et al. (2008) and Tsuji et al. (2012). The first precise measurements of doubly substituted CH4, specifically Δ18 (combined Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2) or Δ13CH3D were published in 2014 (Ono et al., 2014; Stolper et al., 2014a, b). Young et al. (2017) reported on the first 12CH2D2 data from laboratory and natural CH4 sources. Since then, these measurements have become more relevant, particularly within the isotope geochemistry community. Measuring Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 from ambient air samples, however, is more challenging as it requires the collection and quantitative extraction of CH4 from about 1000 L of air (1 m3). The first Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 measurements from the atmosphere, based on ambient air collections in Maryland (USA) and Utrecht (Netherlands), differed from model predictions of the atmosphere based on certain assumptions of source and sink reaction signatures (Chung and Arnold, 2021; Haghnegahdar et al., 2017, 2023; Sivan et al., 2024). The discrepancy could therefore come from either incorrectly assigned kinetic isotope effects associated with sink reactions or the assumptions regarding source signatures, or both (Haghnegahdar et al., 2023; Sivan et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023b). This underscores the importance of obtaining improved constraints on source signatures and the isotope effects associated with sink reactions for improving the utility of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 in the study of atmospheric CH4.

For this study, we have compiled an open-source database (Defratyka et al., 2025, https://doi.org/10.5285/51ae627da5fb41b8a767ee6c653f83e6) of existing measurements of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2, including studies where only Δ13CH3D was measured, from peer-reviewed scientific journal publications. The database contains almost 1500 values of doubly substituted isotope ratio measurements, from about 75 peer-reviewed scientific publications. The database is designed for utilization by the geochemistry and atmospheric science communities. This paper describes the collected Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 values that are included in the database. Our purpose is to present the current knowledge of doubly substituted isotopologues of CH4 and identify existing gaps that presently limit our ability to apply Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 to understanding of atmospheric CH4.

2.1 Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 notations and calibration

A comprehensive review of the theory and nomenclature of doubly substituted isotopologue geochemistry is detailed in Eiler (2007, 2013), Wang et al. (2004) and Young et al. (2016, 2017). Briefly, doubly substituted isotopologue ratios of CH4 are reported and parameterized as Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 values, defined to quantify a measured difference in the isotopologue ratios relative to a random distribution:

Where: and are the measured isotopologue ratios of and , respectively, and and are the calculated isotopologue ratios of and , respectively, based on the assumption of a random distribution of isotopes amongst all stable isotopologues.

As an effect, the isotopologue ratio approaches that based on a random distribution under high-temperature equilibrium conditions, which by definition results in Δ13CH3D or Δ12CH2D2 values of zero (e.g., Douglas et al., 2016; Eiler, 2007, 2013; Stolper et al., 2014a; Young, 2019). It should be noted that non-zero values of Δ13CH3D or Δ12CH2D2 can result from the simple mixing of two separate CH4 pools with distinct bulk isotopic compositions, without any chemical or physical processes inducing isotopic fractionation (e.g., Young et al., 2016).

In this paper, the terms “enriched” and “depleted” refer to comparative values of Δ13CH3D or Δ12CH2D2 – higher numbers as enriched and lower numbers as depleted – for example when comparing samples of CH4, products and reactants of a chemical reaction, or the evolution of CH4 in a physical process.

2.2 Existing instrumentation

The measurement of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 is resource intensive, requiring specialised facilities that are currently not widely available (e.g., Eiler, 2007; Liu et al., 2024b; Ono et al., 2014; Sivan et al., 2024; Stolper et al., 2014a; Young et al., 2017). Magnetic sector High Resolution Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (HR-IRMS) is the most common method to measure Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 (Dong et al., 2020; Eldridge et al., 2019; Haghnegahdar et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2024b; Sivan et al., 2024; Stolper et al., 2014a; Sun et al., 2023; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023a; Young et al., 2016, 2025; Zhang et al., 2021). The first magnetic sector HR-IRMS instrument developed for this purpose was the non-commercial prototype model of the Thermo Scientific 253 Ultra HR-IRMS (developed and installed solely at the California Institute of Technology) that was able to measure a value of the combined 13CH3D and 12CH2D2 abundances via a parameter defined as Δ18 (Eiler, 2013; Stolper et al., 2014a, b; Stolper et al., 2015). A large-radius gas-source multiple-collector isotope ratio mass spectrometer capable of operating up to a mass resolving power (MRP) of 80 000 (Panorama, Nu Instrument) was the first developed HR-IRMS to measure separately Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 (Young et al., 2016, 2017). This was followed by the commercially-available production model of the Thermo Scientific Ultra HR-IRMS that can also measure Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 and routinely achieves a MRP of 30–35 000 (e.g., Eldridge et al., 2019; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Wang et al. 2023a; Sivan et al., 2024). The obtained MRP allows to achieve precise measurements for sample of > 2 mL STP (standard temperature and pressure) of CH4 (∼ 80 µmol) for Panorama (e.g., Labidi et al., 2020) and 3 ± 1 mL STP for Ultra (Sivan et al., 2024). Measurements of smaller volume of CH4 sample result in larger uncertainties caused by degraded counting statistic. The detailed description of the performance of these instruments and measurement protocols for different laboratories can be found in the cited references above.

Distinct from mass spectrometry, measurements of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 are also possible owing to developments in infrared absorption spectroscopy using quantum cascade lasers (TILDAS, Aerodyne Research) operated in near room temperature with narrow line widths and high power (Chen et al., 2022; Gonzalez et al., 2019; Ono et al., 2014; Prokhorov and Mohn, 2022; Zhang et al., 2025). The first TILDAS instrument to achieve high precision Δ13CH3D measurements was demonstrated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2014 (Ono et al., 2014). Δ13CH3D measurement by the TILDAS instrument are achieved using the absorption line in a spectral region around 8.6 µm, as there are fewer interferences from hot bands (Ono et al., 2014). Gonzalez et al. (2019) presented a possibility to implement TILDAS to measure Δ12CH2D2 with precision of 0.5 ‰. Routinely, TILDAS measurements requires 10 mL of CH4 for Δ13CH3D measurements and 20 mL for Δ12CH2D2 (e.g., Gonzalez et al., 2019; Ono et al., 2014). Recently, Zhang et al. (2025) were able to reduce the required volume of CH4 to 3-7 mL STP for Δ13CH3D and to 10 mL STP for Δ12CH2D2, via further instrument optimization.

HR-IRMS signal stability of the detected ions at very low ion currents is key to enable precise isotope ratio measurement through signal acquisition over several hours or even days (e.g., Sivan et al., 2024; Stolper et al., 2014a; Young et al., 2016). Across instrumentation, internal precision and external reproducibility are comparable between laboratories and instruments, achieving down to 0.35 ‰ for Δ13CH3D and 1.35 ‰ for Δ12CH2D2, depending on the measurement technique. The TILDAS and Panorama systems were cross-calibrated on the same set of carbon and hydrogen isotopically characterised laboratory working standards for CH4 to ensure accuracy between different analytical systems (Ono et al., 2014; Young et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2025).

At thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium, Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 values can be linked to a CH4 formation temperature via monotonic functions, presented in Table S1 in the Supplement (Beaudry et al., 2021; Douglas et al., 2017; Eldridge et al., 2019; Gruen et al., 2018; Liu and Liu, 2016; Ono et al., 2014; Stolper et al., 2014a; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Webb and Miller, 2014; Young et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). Different theoretical calculations have been used to obtain these relationships but discrepancies among them are smaller than the current analytical uncertainties. Currently, equilibrated gas experiments along with these theoretical calculations are the basis for calibrating Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 measurements via either magnetic sector HR-IRMS or laser spectroscopy (Eldridge et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2024b; Ono et al., 2014; Sivan et al., 2024; Stolper et al., 2014a; Wang et al., 2015).

2.2.1 Samples extraction and purification

Quantitative extraction and complete purification of CH4 from natural samples is currently necessary to attain the required precision and accuracy to detect differences in clumped isotopic composition (Eiler, 2007; Prokhorov and Mohn, 2022; Safi et al., 2024; Sivan et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2023; Young et al., 2017). Two main methods have been applied so far across laboratories. One employs cryogenic trapping at near absolute zero temperature using a Helium cryostat (Stolper et al., 2014a) and the other have used chromatographic separations techniques (Young et al., 2017).

Measuring doubly substituted isotopologues in ambient air is a major analytical challenge. Since krypton has a similar concentration in the atmosphere and boiling point as CH4 (Kr: 1.14 ppm in the atmosphere, −153.4 °C boiling point; CH4: 1.93 ppm, −161.5 °C), it makes separation by fractional distillation alone impossible. Recently, combined gas chromatography and cryogenic methods were successfully implemented to purify CH4 from 102-103 L of ambient air to measure both Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2. These approaches generally involve the pumping of large volumes of air through sequential cryogenic traps that selectively isolate CH4 from other contaminants using established absorbents (Haghnegahdar et al., 2023; Sivan et al., 2024).

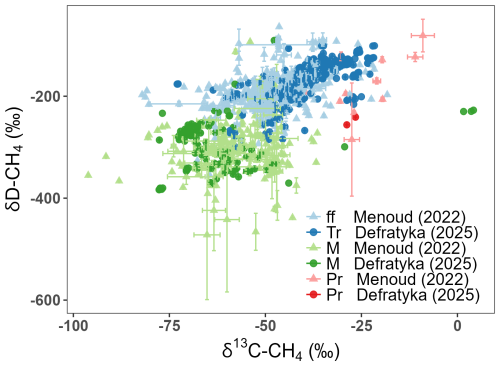

3.1 Data gathering

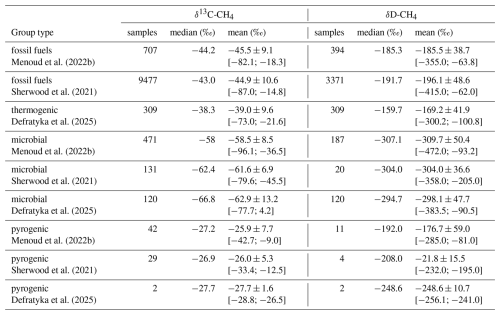

The compilation of this doubly substituted CH4 isotopologues database is inspired by similar efforts of existing databases for bulk isotopes of CH4 (Lan et al., 2021; Menoud et al., 2022a, b; Sherwood et al., 2017, 2021). To verify if the compiled data compares well with previous studies, Fig. 1 and Table 1 present bulk isotopes from this database in the reference to previously reported δ13C-CH4 and δD-CH4 (Menoud et al., 2022a; Sherwood et al., 2021). Across compared group types, our additional bulk isotope ratio data fall within the established ranges. Fossil fuel and thermogenic source signatures overlap, however, they are not strictly equivalent. Thermogenic CH4 in our dataset is slightly enriched (δ13C-CH4: −39.0 ± 9.6 ‰; δD-CH4: −169.2 ± 41.9 ‰), compared to fossil fuel. For the comparison, only terrestrial microbial (e.g., agriculture, lakes, wetlands) from this database is compared with previously compiled data and shows strong agreement with the range of previous microbial samples, with depleted δ13C-CH4 and δD-CH4 values (δ13C-CH4: −62.9 ± 13.2 ‰; δD-CH4: −298.1 ± 47.7 ‰). Pyrogenic methane, though represented by only two samples in the new database, shows δ13C-CH4 and δD-CH4 values consistent with previous studies. This alignment supports the representativeness of our inferred doubly substituted CH4 isotopologues ratio source signatures for use alongside the bulk isotope ratios in global modelling of the CH4 budget. Our database also provides further additional measurements of the bulk isotopes to aid in further work to refine the source signatures δ13C-CH4 and δD-CH4.

Figure 1Database entries plotted as δ13C-CH4 versus δD-CH4 alongside the Menoud et al. (2022a) database. Error bars are taken from original studies. ff: fossil fuels, Tr: thermogenic, M: microbial, Pr: pyrogenic.

Table 1Comparison across the three databases of δ13C-CH4 and δD-CH4 by group type. The mean value is reported with ±1 standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values in brackets.

The references included in the database of doubly substituted CH4 isotopologues comprise mostly peer-reviewed articles, with a smaller percentage from conference papers. The aggregated studies were carried out between 2014 and 2025 across 10 laboratories worldwide. As the aim of this study is to include all existing studies of doubly substituted isotopologue ratios, we also incorporated results from laboratory experiments, and of CH4 dissolved in water (i.e. in oceans, wetlands, and inland waters), which were not included in bulk isotopes databases.

3.1.1 The structure of the database

For efficient utilization of the database, we start with parameters (column names) from the databases of Sherwood et al. (2017, 2021) and Menoud et al. (2022a). Then, we added the parameters to better represent the characteristics of doubly substituted isotope ratio measurements. Selected parameters are described in the metadata of the database (https://doi.org/10.5285/51ae627da5fb41b8a767ee6c653f83e6, Defratyka et al., 2025). Collection and analysis dates, along with instrument and measurement laboratory are included to facilitate comparison between studies. For each entry of Δ18, Δ13CH3D or Δ12CH2D2, the number of samples, measured value, uncertainty, and type of uncertainty are provided. The parameter “other tracers” was added to include information about other tracers collected alongside doubly substituted isotopologues and bulk isotope ratio measurements of CH4. This parameter can be used to filter and group data for the further processing by database users. We also added the “lab field” parameter to make it easier to filter the database based on whether the sample was collected in the field or obtained from a laboratory experiment.

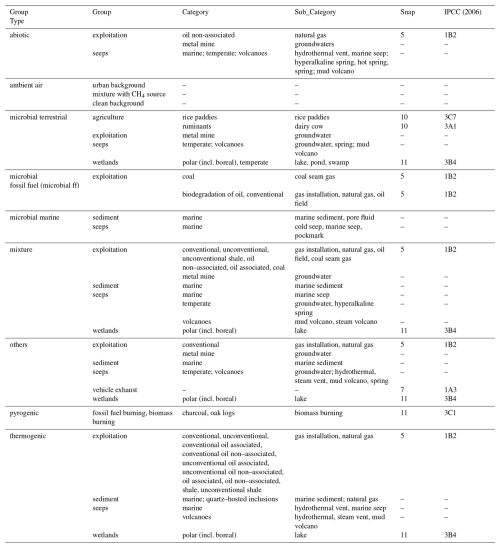

For samples collected from the field, we provided exact location (latitude and longitude), coming from the original article or approximate location, estimated based on geographical information in the article. The parameter “coordinates from primary source” was added to indicate if sampling location was given in the original article. We used the parameters documented by Menoud et al. (2022a) to describe the CH4 source for field samples: group type, group, category and subcategory but with modifications to better reflect properties of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 studies conducted so far (Table 2). For example, in group type, we divided microbial sources into three categories: microbial terrestrial, microbial fossil fuels (microbial ff) and microbial marine. Additionally, we incorporated a parameter “sources specification” to add any information coming from the primary studies' publications that did not match the already included source parameters (e.g., thermodynamic disequilibrium or equilibrium, natural gas maturity, sources mixture). Parameters: “sample type”, “reservoir type”, “depth type” (i.e., unit of reservoir depth from original paper) and “depth” were included for the description of field sampling conditions.

Whenever possible, we connected these groups and categories to the broadly used Selected Nomenclature for Air Pollution (SNAP) and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Changes (IPCC, guidelines 2006) emissions categories for field samples (Table 2). The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) inventories are compatible with IPCC nomenclatures, which facilitates implementation of the database and comparison with existing emissions inventories (details in Sect. 4.3.1). In the database, samples from laboratory experiments, ambient air, and volcano (both mud volcano and steam volcano) measurements are not linked to SNAP and IPCC categories. Also, the SNAPP and IPCC categories were not allocated to groundwater nor deep marine samples (i.e., marine seeps, sediments, and pore fluid), as they represent insignificant sources of CH4 to the atmosphere.

Table 2Group type, group, category, and subcategory of CH4 sources for field samples with SNAP and IPCC categories, based on source categories from Menoud et al. (2022a, b).

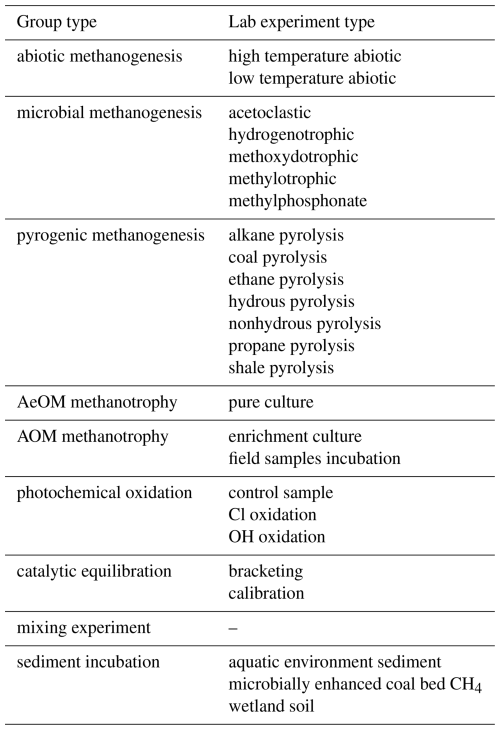

For samples coming from laboratory experiments, we added a specification of the type of laboratory experiment (e.g., abiotic or microbial methanogenesis, pyrolysis experiment, AOM or AeOM methanotrophy) in the group type column (Table 3). Also, parameters “lab experiment type” and “lab experiment detail” were added to include details of conducted experiments. “Catalytic equilibration” experiments are focused on defining the thermal equilibration curve, used for the instruments calibration (Eldridge et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2024b; Ono et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2019; Young et al., 2017).

Due to variations in measurement protocols across laboratories, uncertainties are reported in different ways and therefore we reported uncertainty per entry as described in the database. Most of the laboratories report one or two internal standard errors (int SE) to reflect precision based on HR-IRMS counting statistics (e.g., Ash et al., 2019; Douglas et al., 2016, 2017; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023a; Young et al., 2017). Others use external reproducibility, expressed as one or two external standard deviations (ext SD) (Eldridge et al., 2019; Giunta et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2024a; Warr et al., 2021). When one sample is measured more than once, one SE or two SE are reported as uncertainty in the database (Stolper et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018, 2024a). For some studies, uncertainty is reported as 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) (e.g., Beaudry et al., 2021; Lalk et al., 2024; Ono et al., 2014).

As studies were made over time by different laboratories, not all required database parameters were included in existing peer-reviewed articles. For the future, proposed parameters should ideally be published with data. Additionally, a consistent description of CH4 sources, group type, group, category, subcategory and laboratory experiment type, using the parameters proposed in Tables 2 and 3 is encouraged to facilitate interpretation and intercomparison between laboratories and methods.

4.1 Data summary

Out of all data entries, field samples comprise 958 entries, while 517 entries come from laboratory experiments. Of these, 53 % of entries report only Δ18 or Δ13CH3D. Potentially, the lack of 12CH2D2 measurements can hinder data interpretation, especially for microbial, abiotic or mixed samples, where Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 can be modified differently (e.g., Douglas et al., 2017; Giunta et al., 2019; Gruen et al., 2018; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Warr et al., 2021; Young et al., 2016, 2017). To avoid data misinterpretation, other tracers, for example radiocarbon or seismic reflection data, must be measured alongside to Δ13CH3D (e.g., Chowdhury et al., 2024; Douglas et al., 2020).

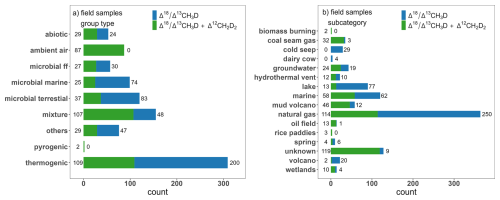

Regarding the parameter “group type”, thermogenic samples contribute 32 % to the field samples, while there is low representation of pyrogenic samples (0.21 % of field samples) (Fig. 2). “Others” is a broad group type of field samples with ambiguous origin from various sources (e.g., natural gas, groundwaters from metal mines, marine and mud volcano samples), where it was not possible to clearly determine the group type based on isotopes and other tracers. Hypothesized origins of these samples are given as “source specification” parameter in the database. Also, vehicle exhaust samples are classified as “others”, as different processes can cause CH4 emissions from the exhaust (Sun et al., 2025b). Additionally, for samples where two different sources of CH4 were mixed, indicated as group type “mixture”, more information on the type of mixture is added under the parameter “source specification” in the database. For ambient air “group type”, distinction between background samples and mixture of ambient air and gas coming from CH4 source (e.g., gas sample collected above wetland, (Haghnegahdar et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2025b)) was made using the “group” parameter.

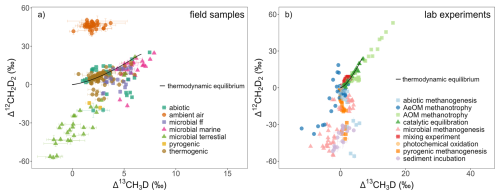

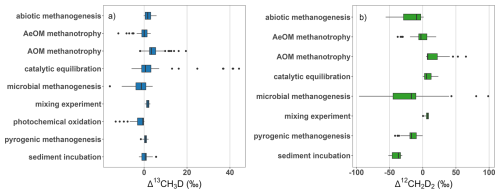

The distribution of measurements in Δ13CH3D versus Δ12CH2D2 space is presented in Fig. 3, both for field samples and laboratory experiments. To simplify data interpretation, field samples categorized as “others” or “mixture” are omitted. Also, samples where ambient air is mixed with the gas from CH4 source are omitted. The majority of thermogenic samples fall close to the thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium curve, with a few samples having more depleted Δ12CH2D2 than predicted (details in Sect. 4.2.). Microbial marine and microbial ff samples are near or at thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium but with some enrichment relative to equilibrium observed. Most of the microbial terrestrial samples (e.g., lakes, wetlands or agriculture) are clearly depleted in both Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2, relative to the equilibrium. Different ratios for microbial terrestrial compared to microbial ff and microbial marine suggests different methanogenesis reactions or additional processes, such as methanotrophy or mixed patterns of microbial carbon cycling within in these environments (details in Sect. 4.2). Regarding abiotic CH4, most of the samples are out of thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium (e.g., Douglas et al., 2020; Labidi et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2023; Young et al., 2017). It must be noted, that abiotic CH4 is empirically one of the least well characterized endmembers, both in terms of field and laboratory studies.

Figure 3Database entries plotted as Δ13CH3D versus Δ12CH2D2. Error bars are taken from original studies (details in Sect. 3.1.1). (a) fields samples based on 247 entries, where samples categorized as “others”, “mixture” and “ambient air mixed with CH4 source” are omitted for simplicity. (b) Laboratory experiments based on 210 entries. Laboratory experiments with deuterium-enriched water substrate (Gruen et al., 2018; Li et al., 2024, 2025a; Taenzer et al., 2020) are not included as they do not appear under normal incubation or environmental conditions. A solid black line represents the thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium curve, using equations from Young et al. (2017).

For laboratory experiments, the deviation from thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium depends on the studied methanogenesis pathway or the type of methanotrophy (aerobic (AeOM) versus anaerobic (AOM) CH4 oxidation) (details in Sect. 4.2). For example, AOM methanotrophy experiments show a large enrichment for both Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 (Liu et al., 2023; Ono et al., 2021). Notably, Gruen et al. (2018), Li et al. (2024, 2025a), and Taenzer et al. (2020), carried out incubations with deuterium-enriched substrate to explore mechanisms behind combinatorial effects. Thus, observed clumped isotopologues do not represent the isotopic values of natural-occurring microbial CH4 and should be carefully re-interpreted.

Regarding pyrogenic methanogenesis, some samples have doubly-substituted isotope ratio compositions consistent with thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium, while others create more depleted values, due to a combination of kinetic isotope effects, combinatorial effects, and varying degrees of hydrogen isotope exchange (Dong et al., 2021; Eldridge et al., 2023; Shuai et al., 2018a). The abiotic synthesis of CH4 in laboratory-controlled experiments shows enriched Δ13CH3D, consistent with thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium, associated with systematically depleted Δ12CH2D2, due to combinatorial effects (Young et al., 2017, Labidi et al., 2024).

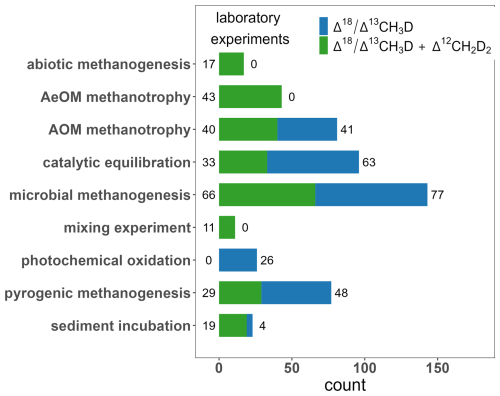

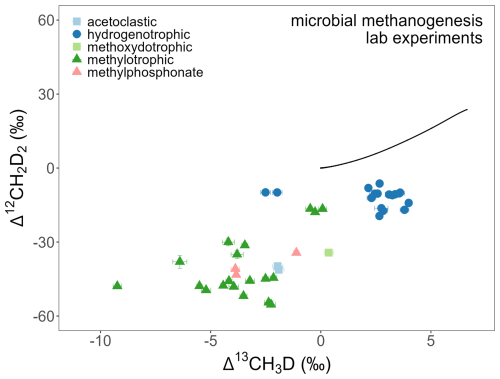

About 27 % of the laboratory experimental entries come from studies on microbial methanogenesis, focused on various pure cultures of methanogenic archaea (e.g., acetoclastic, hydrogenotrophic and methylotrophic methanogenesis) (Fig. 4) (Douglas et al., 2016, 2020; Giunta et al., 2019; Gruen et al., 2018; Rhim and Ono, 2022; Stolper et al., 2015; Warr et al., 2021; Young et al., 2017). Notably, Li et al. (2025a) conducted methanogenesis experiment where few data points come from extremely deuterium-enriched water (δD of water about 3000 ‰ and 8000 ‰). Such high δ2H of water cannot be found in the nature, thus obtained CH4 has very atypical isotopic values (Fig. 5).

4.4 % of laboratory samples, classified as sediment incubation, were collected in the field and incubated in controlled laboratory conditions (Douglas et al., 2020; Haghnegahdar et al., 2023, 2024; Ijiri et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2024a). A single laboratory experiment focused on photochemical oxidation by OH and Cl was also conducted, however, only Δ13CH3D was measured (Whitehill et al., 2017). A laboratory experiment focused on mixing of two CH4 sources, containing different bulk isotopic compositions, was conducted to confirm mixing curve delivered from theoretical calculation, related to the definition of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 (Young et al., 2016).

Figure 5Δ13CH3D versus Δ12CH2D2 for microbial methanogenesis laboratory experiments. Laboratory experiments with deuterium-enriched water substrate (Gruen et al., 2018; Li et al., 2024, 2025a; Taenzer et al., 2020) are not included as they do not appear under normal incubation or environmental conditions.

4.2 State of knowledge about CH4 doubly-substituted isotopologue ratios

Methane is produced at the surface and in subsurface environments via biogenic (microbial), thermogenic, or abiotic processes, while the majority of the CH4 emitted to the atmosphere comes from microbial, thermogenic, and pyrolytic (biomass and biofuel burning) sources (e.g., Saunois et al., 2025; Schoell, 1988; Stolper et al., 2018). Thermogenic CH4 forms by the thermally-activated breakdown of organic molecules, where “primary thermogenic” is a term used to describe CH4 produced from kerogen and “secondary thermogenic” is used to describe the breakdown of long-chain hydrocarbons (e.g., Lalk et al., 2023; Stolper et al., 2018). Stolper et al. (2014b) proposed that thermogenic CH4 is predominantly in thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium at its formation temperature, which was supported by studies focused on natural gas or volcanic samples (Beaudry et al., 2021; Douglas et al., 2016, 2017; Jiang et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2023; Rumble et al., 2018; Stolper et al., 2014b, 2015, 2018; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2021; Young et al., 2017). Formation temperatures calculated from doubly substituted isotope ratio measurements can help to determine the natural gas maturity and distinguish “atypical” thermogenic gas (from shallow or immature systems to deep or over-mature systems) from abiotic CH4 (Jiang et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2023; Li et al., 2025b; Shuai et al., 2018b). Some exceptions of doubly substituted isotope ratios deviating from thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium were observed from unconventional, oil-non-associated or oil-associated gas reservoirs (Fig. 6) (Douglas et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2023; Lalk et al., 2022; Stolper et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2021), which is consistent with laboratory pyrolysis experiments and gas generation models implying at least partly kinetically-driven signatures (Dong et al., 2021; Eldridge et al., 2023; Shuai et al., 2018a; Xia and Gao, 2019). For low maturity or oil-associated natural gas, a contribution from microbial sources can occur, for example due to CH4 generation during oil biodegradation (e.g., secondary microbial CH4). However, the likelihood that microbial CH4 has both Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 within the thermogenic range remains low (Giunta et al., 2019; Lalk et al., 2022; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2021).

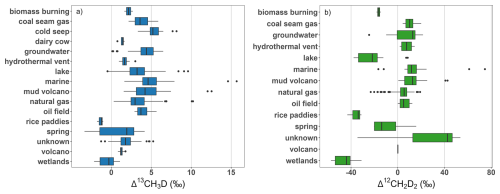

Figure 6Summary of the distribution of measurement results, (a) Δ13CH3D and (b) Δ12CH2D2 from field studies based on simplified subcategories as described in Sect. 4.3.

Microbial CH4 is produced by microorganisms via three main pathways: hydrogenotrophic, acetoclastic, and methylotrophic methanogenesis, with the first two being the predominant (Conrad, 2005; Thauer, 1998). Typically, subsurface microbial CH4 from geological basins is mostly generated through the hydrogenotrophic pathway, where doubly substituted isotope ratios tend towards thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium (Figs. 3 and 5) (Ash et al., 2019; Douglas et al., 2016, 2017, 2020; Giunta et al., 2019; Shuai et al., 2021; Stolper et al., 2015; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2024a; Warr et al., 2021; Young et al., 2017). Studies of pore water from the Michigan Basin, showed that deep subsurface CH4 can also be generated by acetoclastic methanogenesis at thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium for 13CH3D but at substantial disequilibrium for 12CH2D2 (Jautzy et al., 2021). The majority of microbial CH4 from shallow freshwater environments is generated during acetoclastic methanogenesis, which can result in strong depletion for both 13CH3D and 12CH2D2 (Figs. 3 and 5) (Conrad, 2005; Douglas et al., 2016, 2017, 2020; Haghnegahdar et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025a; Stolper et al., 2014b; Wang et al., 2015; Whiticar, 1999; Young et al., 2017). In systems with presumed slow CH4 generation rates, favouring enzymatic isotopic reversibility, microbial CH4 likely can form at or near thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium, while in systems with rapid CH4 formations, microbial CH4 tends to depart from thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium (Douglas et al., 2020; Shuai et al., 2021; Stolper et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015).

Methane can also be produced abiotically, for example via Sabatier reactions linked to hydrogen production from serpentinization in hydrothermal systems (Cumming et al., 2019; Douglas et al., 2017; Labidi et al., 2020; Nothaft et al., 2021; Ojeda et al., 2023; Suda et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2018; Young et al., 2017). It has been observed from deep groundwater seeps accessed via or within deep subsurfaces layers, for instance in metal mines, where it can also mix with microbial CH4 followed by re-equilibration (Nothaft et al., 2021; Warr et al., 2021; Young et al., 2017). Typically, abiotic CH4 is produced at temperatures exceeding 250 °C in seafloor hydrothermal fluids or in the continental seeps, springs and fracture waters at temperatures lower than 100 °C (Etiope and Sherwood Lollar, 2013; Labidi et al., 2024; Young et al., 2017). During controlled laboratory synthesis under hydrothermal conditions, the majority of the Δ13CH3D measurements closely reflect the temperature of abiotic CH4 generation (based on thermodynamic isotopic equilibrium). Δ12CH2D2 was observed with depletions down to −40 ‰, which can be attributed to a combinatorial effect associated with the various steps of hydrogen addition to carbon occurring during CH4 formation (Labidi et al., 2024).

Using doubly substituted isotope ratio measurements, the mixed thermogenic-microbial origin of CH4 was observed in marine environments, including CH4 clathrates (Giunta et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021), lakes (Douglas et al., 2016), mud volcanoes (Lin et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2024a; Rumble et al., 2018), oil fields (Tyne et al., 2021) and natural gas (Douglas et al., 2017; Giunta et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2023; Lalk et al., 2022; Stolper et al., 2014b, 2015; Thiagarajan et al., 2020, 2022). Mixing between different CH4 sources (containing different bulk isotopic compositions) in different proportions creates a non-linear relationship in Δ12CH2D2 vs Δ13CH3D space. Measurement of both doubly-substituted isotope ratios therefore provides additional information to help define the mixed end members and understand if physical or chemical transformation processes have taken place (e.g., Douglas et al., 2016; Young et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021).

Notably, existing studies showed a range of doubly-substituted isotope ratios for mud volcano samples, suggesting their different origins (thermogenic, microbial, abiotic or mixed) and potentially reflecting subsequent alteration processes such as AOM (Ijiri et al., 2018; Lalk et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023, 2024a; Rumble et al., 2018). Additionally, Δ13CH3D was used to demonstrate a microbial origin of CH4 in deep subsurface coal beds in the north-western Pacific (Inagaki et al., 2015) and shallow subsurface mud volcano in the Nankai accretionary complex (Ijiri et al., 2018), which could otherwise be incorrectly identified as thermogenic sources. Also, Δ12CH2D2 vs Δ13CH3D suggested mixing of thermogenic and microbial CH4 in coal bed reservoirs (Wang et al., 2024b, c).

Combinatorial effects occur when a molecule contains indistinguishable atoms of the same element derived from pools with different isotope ratios. This purely mathematical phenomenon comes from the definition of doubly-substituted isotope ratio in reference to the stochastic distribution and has been predicted theoretically (Röckmann et al., 2016; Yeung, 2016) and demonstrated experimentally for CH4 (Labidi et al., 2024; Taenzer et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2024a). Among the two mass-18 isotopologues of CH4, only Δ12CH2D2 can be influenced by combinatorial effects, as it features two indistinguishable deuterium substitutions for hydrogen. Combinatorial effects for Δ12CH2D2 values must be taken into account in low-temperature abiotic or biotic systems where the hydrogen atoms of CH4 originates from multiple reservoirs, which has been observed in microbial samples (Giunta et al., 2019; Jautzy et al., 2021; Young et al., 2017), mud volcanos (Liu et al., 2024a), natural gas (Shuai et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2021), or during abiotic, microbial and pyrogenic methanogenesis experiments (Dong et al., 2021; Eldridge et al., 2023; Labidi et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025a). Notably, Eldridge et al. (2023) showed that combinatorial effects alone cannot explain the non-equilibrium of Δ12CH2D2, observed in their pyrogenic methanogenesis experiments focused on CH4 formation from methyl precursors (i.e. ethane). They pointed out the role of other important processes such as the influence of kinetic isotope effects and inheritance reactions (i.e., inheriting “clumps” from methyl groups in the precursor molecule), in addition to combinatorial effects.

Figure 7Summary of the distribution of measurement results, (a) Δ13CH3D and (b) Δ12CH2D2 from laboratory studies based on group types as described in Sect. 4.1. The outliers for catalytic equilibration come from the sample measured at the beginning of the experiment, when equilibration on the catalyst did not start yet.

Before emission to the atmosphere, CH4 can be consumed through aerobic oxidation (AeOM) or anaerobic oxidation (AOM). In terrestrial ecosystems (e.g., wetlands) and oxygenated marine water columns, AeOM plays a crucial role, while in gas seeps and sulphate-rich marine sediments, AOM likely dominate causing inhibition of CH4 emissions to the atmosphere (e.g., Wang et al., 2016 and references therein). Minor depletions in Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 were observed in AeOM-dominated systems, but low-temperature equilibrium or significant enrichments in Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 were observed in the case of AOM (Figs. 3 and 7) (Giunta et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023; Ono et al., 2021). One hypothesis states that the reversibility of initial steps of AOM promotes thermodynamic equilibration (Ash et al., 2019; Giunta et al., 2022; Ono et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Alternatively, another hypothesis proposes that near-thermodynamic equilibrium of doubly substituted isotope ratios in marine sediments can be attained via a slow rate of methanogenesis, with reversible enzymatic reaction steps (Douglas et al., 2020; Shuai et al., 2021; Stolper et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). As AeOM and AOM have distinctive kinetic isotope effects in natural settings, doubly-substituted isotope ratios may be used to track and differentiate both AeOM and AOM in nature (Adnew et al., 2025; Ash et al., 2019; Giunta et al., 2019, 2022; Krause et al., 2022; Li et al., 2024; Tyne et al., 2021; Warr et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

In the troposphere, reaction with OH is the primary removal mechanism of CH4 (90 %), with other minor contributions from microbial oxidation in soils and vegetation, loss to the stratosphere, and reactions with tropospheric Cl (e.g., Saunois et al., 2025). Overall, isotopologues containing bonds of lighter isotopes are preferentially removed through photochemical oxidation, leading to an enrichment in heavier isotopologues of the remaining CH4 pool (Table S2 in the Supplement) (e.g., Haghnegahdar et al., 2017; Whitehill et al., 2017). Laboratory experiments showed that photochemical oxidation by OH has only a minor impact on Δ13CH3D of tropospheric CH4 (i.e. the 13C-D bond does not react significantly slower than that calculated based on equivalent singly substituted reactants) (Whitehill et al., 2017). Thus, measurements of Δ13CH3D in the atmosphere can provide constraints on CH4 source strengths, while Δ12CH2D2 is predicted to provide information on CH4 sink strength, as implemented in global scale atmospheric models (Chung and Arnold, 2021; Haghnegahdar et al., 2017; Whitehill et al., 2017). Aside from the atmospheric models, Wang et al. (2023b) used machine learning incorporated with a random forest model to predict steady-state atmospheric CH4 doubly substituted isotope ratios. The first measurements of the doubly substituted isotope ratio of CH4 in the atmosphere were more depleted for both Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 than predicted by atmospheric models and available source signature information (Chung and Arnold, 2021; Haghnegahdar et al., 2017, 2023; Sivan et al., 2024). Haghnegahdar et al. (2023) proposed that differences between measurements and predictions required depleted doubly substituted isotopic signature values for the (total) source flux than previously assumed. On the other hand, Sivan et al. (2024) highlighted that the observed discrepancy could also be caused by inaccuracy in the theoretical values of the kinetic isotopic effect (KIE) of CH4 reactions with OH, Cl and soils sinks. They indicated that a small adjustment in the sink KIE, along with slightly lower source mixture than previously assumed, could align atmospheric and source doubly substituted isotopic signatures (Sivan et al., 2024).

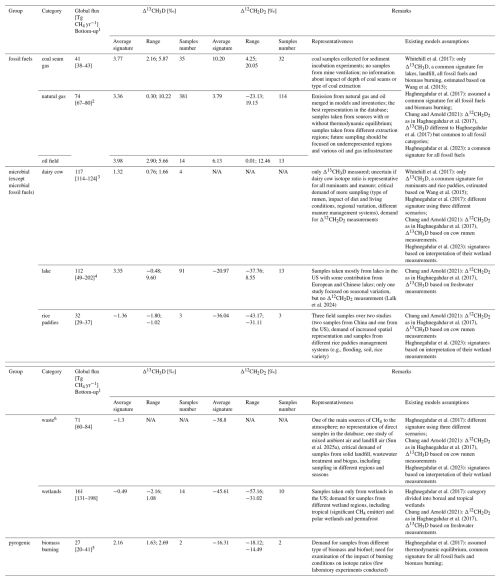

Table 4Global CH4 emissions and inferred doubly substituted CH4 isotope ratio signatures with remarks on the current representativeness of main CH4 sources to the atmosphere and requirements for future studies. Uncertainties of global emissions are reported as [min-max] range. NA = non available.

1 CH4 global flux from Saunois et al. (2025) for the year 2020. 2 CH4 global flux for natural gas and oil merged into one category in Saunois et al. (2025). 3 enteric fermentation and manure category in Saunois et al. (2025). 4 inland freshwater category in Saunois et al. (2025). 5 biomass and biofuel burning together from Saunois et al. (2025). 6 Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 of waste sector from indirect measurement (e.g., ambient air mixed with gas from landfill) from Sun et al. (2025a).

4.3 Data representatives and importance for atmospheric sciences

The distribution of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 derived from field samples per simplified subcategory is plotted on Fig. 2b, while Figs. 6 and 7 present box plots for measured doubly substituted isotopes from field samples and laboratory experiments, respectively. For simplicity, in Figs. 2b and 6, and thereafter, some subcategories are merged. Gas installation and natural gas subcategories are merged into natural gas. Hot spring, spring, and hyperalkaline spring are unified as spring. Marine sediment, marine seep, pore fluid and pockmark are grouped as a marine subcategory. Hydrothermal and volcano steam samples are unified as volcano. Finally, swamp and ponds are merged as wetlands, while lakes are in a separate subcategory. Around 40 % of field samples were collected from reservoirs of natural gas (Fig. 2b). About 3 % of field samples come from coal seam gas and 12.5 % come from microbial terrestrial sources. There is a significant representation of marine (12.5 % of field samples) and volcano mud samples (6 % of field samples), although, their emissions to the atmosphere are negligible. For samples categorized as microbial terrestrial, the majority of entries come from lakes (75 % of microbial terrestrial), with a small contribution from agriculture (6 %) or wetland (12 %) samples, which are significant CH4 emitters to the atmosphere. Only Δ13CH3D was measured for four ruminants samples (Lopes et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015). Only three samples from rice paddies have so far been collected, where both Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 were measured (Haghnegahdar et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023a). So far, no waste samples have been collected directly from the source for studies of doubly substituted isotope ratios. The recent studies of Sun et al. (2025a) focused on collection of big volume ambient air samples, where background air was mixed with gas coming from microbial CH4 sources, like wetlands and landfills. Application of a Keeling plot method (Pataki, 2003), allowed determination of targeted sources (Sun et al., 2025a).

Published Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 for natural gas are consistent with a thermogenic origin (Figs. 3 and 6, Tables S3 and S4). Observed outliers come from low maturity or oil-associated natural gas where a microbial contribution could be significant (Kim et al., 2023; Lalk et al., 2022; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2021). No significant variation has been observed in measurements made of biomass burning, dairy cows (ruminants), or rice paddies within the available, limited dataset but this may not reflect the variation within the true population (Tables S3 and S4). Significant variation in both Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 is observed for spring and mud volcano subcategories, as these samples have varying microbial, thermogenic, abiotic, or mixed origins. Finally, a wide distribution is observed for lake samples, potentially originating from seasonal variation in CH4 production, oxidation in the lake subsurface or methanogenic metabolisms involved (Lalk et al., 2024).

For the laboratory experiments, culturing of different strains of archaea and wide variations in experimental parameters resulted in a wide distribution of observed doubly substituted isotopic compositions, especially for Δ12CH2D2 (Fig. 7, Tables S5 and S6). AOM methanotrophy experiments show significant enrichment in both Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 relative to the other categories.

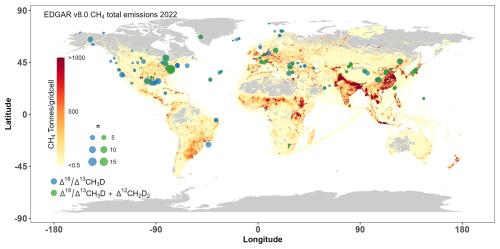

Figure 8Global locations of collected field samples for doubly substituted isotope measurement (blue and green circles) overlayed on an estimate of the total CH4 annual emission rates for year 2022 from the EDGAR v8.0 inventory.

4.3.1 Evaluation of the database in relation to emission to the atmosphere

On a global scale, using a bottom-up approach (e.g., using data-driven and process based models for natural sources and inventories for anthropogenic sources) for the year 2020, anthropogenic emissions contribute about 54 % of the CH4 emissions to the atmosphere, originating from agriculture (40 %), fossil fuel extraction and use (34 %), waste (19 %) and anthropogenic biomass burning (7 %) (Saunois et al., 2025). Wetlands account for most of the natural CH4 emissions (51 %), with a significant contribution from inland freshwaters (35 %) and remaining emission coming from other sources, including onshore and offshore geological emissions (e.g., mud volcanoes, volcanoes, vents, seepages) (Saunois et al., 2025). Regarding the main CH4 emitters to the atmosphere, natural gas and oil are the most represented emission category in the doubly substituted CH4 isotopologue database (39 % of field samples), while coal seams gas samples represent 4 % of the field samples in the database. There are no reported measurements of Δ12CH2D2 for ruminants (4 samples for Δ13CH3D values), and no records of either Δ13CH3D or Δ12CH2D2 from directly sampled waste. Additionally, there is a very limited sample size for some important emissions subcategories such as biomass burning (0.2 %) and rice paddies (0.3 %). As field sampling is time consuming and location-constrained, measurements made this far do not reflect a realistic spatio-temporal variation of doubly substituted isotope ratios, both for anthropogenic and natural CH4 sources. With such limited studies, the current estimated Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 source signatures may not be representative. Thus, some assumptions on the source signature inputs to global scale models of double subsisted isotope ratios have to be made (Table 4). To better reflect Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 of CH4 emission sectors, further sampling should be focused on underrepresented CH4 sources and on numerous conditions affecting emissions from individual sectors, for example impact of reservoir depth and coal type for coal seam gas or impact of diet and living conditions for rumen (Table 4). An effort should be made to measure Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 from thawing permafrost, as it may be a significant source of CH4 to the atmosphere in the future (Douglas et al., 2020; Ellenbogen et al., 2024; Walter Anthony et al., 2024).

In addition to increasing the sampling frequency for the main CH4 sources, an effort should also be made to extend sampling to other areas with significant CH4 emissions to the atmosphere, including super-emitters. Using TROPOMI (TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument) satellite data, super-emitters were detected for coal mining, oil and gas production regions, and along the major gas transmission pipelines (Schuit et al., 2023). The majority of detected super-emitters is related to urban areas (35 % of detected super-emitters), with a possible large contribution from landfills (Schuit et al., 2023), where no direct samples of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 have been taken so far.

Comparing locations of field samples and a map of anthropogenic CH4 emissions, based on EDGAR v8.0 inventories, there is a considerable deficiency in measurements of doubly substituted isotope ratios from numerous locations with elevated CH4 emissions (Fig. 8). No samples have been analysed from regions with significant CH4 emissions, like Central Africa, southwestern South America, India, Pakistan, western China, New Zealand, and Indonesia. There is no data from the EDGAR database for certain areas, such as Siberia and Canada, where increased anthropogenic emissions can occur as well. Furthermore, sampling should be conducted in regions with notable natural emissions, such as wetlands and internal freshwaters, including thawing permafrost.

Data may be accessed from the following DOI: https://doi.org/10.5285/51ae627da5fb41b8a767ee6c653f83e6 (Defratyka et al., 2025).

This study presents a compilation of Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 measurements from field samples and laboratory experiments, from results published between 2014 and 2025, by numerous laboratories. The database is designed for utilization by the geochemistry and atmospheric science communities. The database of doubly substituted isotope ratios comprises 1475 data records from 75 peer-reviewed articles (Figs. 2a and 4). Of this data, 53 % of the database entries report only Δ18 or Δ13CH3D, which can hinder data interpretation, especially for microbial, abiotic or mixed samples, when used without any additional tracer (Chowdhury et al., 2024; Douglas et al., 2017; Giunta et al., 2019; Gruen et al., 2018; Thiagarajan et al., 2020; Warr et al., 2021; Young et al., 2016, 2017). For field samples, 40 % of the data records come from natural gas, mostly from the basins in the US and China. Samples collected from lakes contribute 75 % of microbial terrestrial samples. At the current state, there is a limited representation of samples coming from wetlands and agriculture sources and there is no representation of directly sampled waste sector (Fig. 2b).

As our ability to measure doubly substituted isotopologues of CH4 in the atmosphere improves, a commensurate effort to improve our understanding of source signatures is needed in order to make the very most of these measurements in understanding the global atmospheric CH4 budget. Studies should focus on the main emission sectors to the atmosphere, in particular on underrepresented sectors such as agriculture (e.g., ruminants, manure, rice cultivation), wetlands (including polar), waste and biomass burning. Also new field campaigns should focus on areas with increased CH4 emissions, including super-emitters. An additional effort is also required to provide more ambient air background samples, ideally from remote, clean air sites. To better understand CH4 sinks, more experiments focused on photochemical oxidation by OH and Cl must also be conducted.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-6889-2025-supplement.

Conceptualization: SMD, JMF, TA; Investigation and data curation: GAA, GD, PMJD, DLE, GE, TG, MAH, ANH, NH, VI, JJ, JHK, JL, EL, WL, JL, LHL, JL, LO, SO, JR, TR, BSL, MS, JS, GTV, DTW, EDY, NZ; Formal analysis: SMD; Visualization: SMD; Writing (original draft preparation): SMD; Writing (review and editing): SMD, JMF, TA, GAA, GD, PMJD, DLE, GE, TG, MAH, ANH, NH, VI, JJ, JHK, JL, EL, WL, JL, LHL, JL, LO, SO, JR, TR, BSL, MS, JS, GTV, DTW, EDY, NZ.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

This article is not a product of the U.S. Department of Energy. Views and opinions expressed in this article are the authors' own and do not represent those of the United States Government.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. We gratefully acknowledge the authors and researchers whose previously published work was used for this data aggregation. The data compiled herein are derived from and built upon findings reported in peer-reviewed scientific literature. All original sources have been cited appropriately in the accompanying references.

This research has been supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (grant no. NE/V007149/1) and the European Association of National Metrology Institutes (grant no. 21GRD04 isoMET). Funding for this work came from the UKRI NERC POLYGRAM project NE/V007149/1 (http://www.polygram.ac.uk, last access: 2 December 2025), the EURAMET 21GRD04 isoMET project and the NPL Director's Fund.

This paper was edited by Graciela Raga and reviewed by Glen Snyder and one anonymous referee.

Adnew, G. A., Rockmann, T., Blunier, T., Jørgensen, C. J., Sapper, S. E., Veen, C. van der, Sivan, M., Popa, M. E., and Christiansen, J. R.: Clumped isotope measurements reveal aerobic oxidation of methane below the Greenland ice sheet, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 389, 249–264, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2024.11.009, 2025.

Ash, J. L., Egger, M., Treude, T., Kohl, I., Cragg, B., Parkes, R. J., Slomp, C. P., Sherwood Lollar, B., and Young, E. D.: Exchange catalysis during anaerobic methanotrophy revealed by 12CH2D2 and 13CH3D in methane, Geochem. Perspect. Lett., 26–30, https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1910, 2019.

Basu, S., Lan, X., Dlugokencky, E., Michel, S., Schwietzke, S., Miller, J. B., Bruhwiler, L., Oh, Y., Tans, P. P., Apadula, F., Gatti, L. V., Jordan, A., Necki, J., Sasakawa, M., Morimoto, S., Di Iorio, T., Lee, H., Arduini, J., and Manca, G.: Estimating emissions of methane consistent with atmospheric measurements of methane and δ13C of methane, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 15351–15377, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-15351-2022, 2022.

Beaudry, P., Stefansson, A., Fiebig, J., Rhim, J. H., and Ono, S.: High temperature generation and equilibration of methane in terrestrial geothermal systems: Evidence from clumped isotopologues, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 309, 209–234, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.06.034, 2021.

Chen, C., Qin, S., Wang, Y., Holland, G., Wynn, P., Zhong, W., and Zhou, Z.: High temperature methane emissions from Large Igneous Provinces as contributors to late Permian mass extinctions, Nat. Commun., 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34645-3, 2022.

Chowdhury, A., Ventura, G. T., Owino, Y., Lalk, E. J., MacAdam, N., Dooma, J. M., Ono, S., Fowler, M., MacDonald, A., Bennett, R., MacRae, R. A., Hubert, C. R. J., Bentley, J. N., and Kerr, M. J.: Cold seep formation from salt diapir–controlled deep biosphere oases, P. Natl. Acas. Sci. USA, 121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2316878121, 2024.

Chung, E. and Arnold, T.: Potential of Clumped Isotopes in Constraining the Global Atmospheric Methane Budget, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles, 35, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GB006883, 2021.

Conrad, R.: Quantification of methanogenic pathways using stable carbon isotopic signatures: a review and a proposal, Org. Geochem., 36, 739–752, 2005.

Cumming, E. A., Rietze, A., Morrissey, L. S., Cook, M. C., Rhim, J. H., Ono, S., and Morrill, P. L.: Potential sources of dissolved methane at the Tablelands, Gros Morne National Park, NL, CAN: A terrestrial site of serpentinization, Chem. Geol., 514, 42–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.03.019, 2019.

Defratyka, S., Fernandez, J., and Arnold, T.: Methane doubly substituted (clumped) isotopologues database, NERC EDS Centre for Environmental Data Analysis [data set], https://doi.org/10.5285/51ae627da5fb41b8a767ee6c653f83e6, 2025.

Dong, G., Xie, H., Thiagarajan, N., Eiler, J., Zhang, N., Nakagawa, M., Yoshida, N., Eldridge, D., Stolper, D., Albrecht, N., and Kohl, I. E.: Clumped isotope analysis of methane using HR-IRMS: New insights into origin and formation mechanisms of natural gases and a potential geothermometer, 2020.

Dong, G., Xie, H., Formolo, M., Lawson, M., Sessions, A., and Eiler, J.: Clumped isotope effects of thermogenic methane formation: Insights from pyrolysis of hydrocarbons, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 303, 159–183, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.03.009, 2021.

Douglas, P. M. J., Stolper, D. A., Smith, D. A., Walter Anthony, K. M., Paull, C. K., Dallimore, S., Wik, M., Crill, P. M., Winterdahl, M., Eiler, J. M., and Sessions, A. L.: Diverse origins of Arctic and Subarctic methane point source emissions identified with multiply-substituted isotopologues, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 188, 163–188, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.05.031, 2016.

Douglas, P. M. J., Stolper, D. A., Eiler, J. M., Sessions, A. L., Lawson, M., Shuai, Y., Bishop, A., Podlaha, O. G., Ferreira, A. A., Santos Neto, E. V., Niemann, M., Steen, A. S., Huang, L., Chimiak, L., Valentine, D. L., Fiebig, J., Luhmann, A. J., Seyfried, W. E., Etiope, G., Schoell, M., Inskeep, W. P., Moran, J. J., and Kitchen, N.: Methane clumped isotopes: Progress and potential for a new isotopic tracer, Org. Geochem., 113, 262–282, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.07.016, 2017.

Douglas, P. M. J., Moguel, R. G., Anthony, K. M. W., Wik, M., Crill, P. M., Dawson, K. S., Smith, D. A., Yanay, E., Lloyd, M. K., Stolper, D. A., Eiler, J. M., and Sessions, A. L.: Clumped Isotopes Link Older Carbon Substrates With Slower Rates of Methanogenesis in Northern Lakes, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086756, 2020.

Eiler, J. M.: “Clumped-isotope” geochemistry – The study of naturally-occurring, multiply-substituted isotopologues, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 262, 309–327, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2007.08.020, 2007.

Eiler, J. M.: The Isotopic Anatomies of Molecules and Minerals, Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 41, 411–441, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105348, 2013.

Eldridge, D. L., Korol, R., Lloyd, M. K., Turner, A. C., Webb, M. A., Miller, T. F., and Stolper, D. A.: Comparison of Experimental vs Theoretical Abundances of 13CH3D and 12CH2D2 for Isotopically Equilibrated Systems from 1 to 500 °C, ACS Earth Space Chem., 3, 2747–2764, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.9b00244, 2019.

Eldridge, D. L., Turner, A. C., Bill, M., Conrad, M. E., and Stolper, D. A.: Experimental determinations of carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionations and methane clumped isotope compositions associated with ethane pyrolysis from 550 to 600 °C, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 355, 235–265, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2023.06.006, 2023.

Ellenbogen, J. B., Borton, M. A., McGivern, B. B., Cronin, D. R., Hoyt, D. W., Freire-Zapata, V., McCalley, C. K., Varner, R. K., Crill, P. M., Wehr, R. A., Chanton, J. P., Woodcroft, B. J., Tfaily, M. M., Tyson, G. W., Rich, V. I., and Wrighton, K. C.: Methylotrophy in the Mire: direct and indirect routes for methane production in thawing permafrost, mSystems, 9, https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00698-23, 2024.

Etiope, G. and Sherwood Lollar, B.: Abiotic Methane On Earth, Rev. Geophys., 51, 276–299, https://doi.org/10.1002/rog.20011, 2013.

Giunta, T., Young, E. D., Warr, O., Kohl, I., Ash, J. L., Martini, A., Mundle, S. O. C., Rumble, D., Pérez-Rodríguez, I., Wasley, M., LaRowe, D. E., Gilbert, A., and Sherwood Lollar, B.: Methane sources and sinks in continental sedimentary systems: New insights from paired clumped isotopologues 13CH3D and 12CH2D2, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 245, 327–351, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2018.10.030, 2019.

Giunta, T., Labidi, J., Kohl, I. E., Ruffine, L., Donval, J. P., Géli, L., Çaðatay, M. N., Lu, H., and Young, E. D.: Evidence for methane isotopic bond re-ordering in gas reservoirs sourcing cold seeps from the Sea of Marmara, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 553, 116619, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116619, 2021.

Giunta, T., Young, E. D., Labidi, J., Sansjofre, P., Jézéquel, D., Donval, J.-P., Brandily, C., and Ruffine, L.: Extreme methane clumped isotopologue bio-signatures of aerobic and anaerobic methanotrophy: Insights from the Lake Pavin and the Black Sea sediments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 338, 34–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2022.09.034, 2022.

Gonzalez, Y., Nelson, D. D., Shorter, J. H., McManus, J. B., Dyroff, C., Formolo, M., Wang, D. T., Western, C. M., and Ono, S.: Precise Measurements of 12CH2D2 by Tunable Infrared Laser Direct Absorption Spectroscopy, Anal. Chem., 91, 14967–14974, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03412, 2019.

Gruen, D. S., Wang, D. T., Könneke, M., Topçuoðlu, B. D., Stewart, L. C., Goldhammer, T., Holden, J. F., Hinrichs, K.-U., and Ono, S.: Experimental investigation on the controls of clumped isotopologue and hydrogen isotope ratios in microbial methane, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 237, 339–356, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2018.06.029, 2018.

Haghnegahdar, M. A., Schauble, E. A., and Young, E. D.: A model for 12CH2D2 and 13CH3D as complementary tracers for the budget of atmospheric CH4, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles, 31, 1387–1407, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GB005655, 2017.

Haghnegahdar, M. A., Sun, J., Hultquist, N., Hamovit, N. D., Kitchen, N., Eiler, J., Ono, S., Yarwood, S. A., Kaufman, A. J., Dickerson, R. R., Bouyon, A., Magen, C., and Farquhar, J.: Tracing sources of atmospheric methane using clumped isotopes, P. Natl. Acas. Sci. USA, 120, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2305574120, 2023.

Haghnegahdar, M. A., Hultquist, N., Hamovit, N. D., Yarwood, S. A., Bouyon, A., Kaufman, A. J., Sun, J., Magen, C., and Farquhar, J.: A Better Understanding of Atmospheric Methane Sources Using 13CH3D and 12CH2D2 Clumped Isotopes, J. Geophys. Res., 129, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JG00817, 2024.

Ijiri, A., Inagaki, F., Kubo, Y., Adhikari, R. R., Hattori, S., Hoshino, T., Imachi, H., Kawagucci, S., Morono, Y., Ohtomo, Y., Ono, S., Sakai, S., Takai, K., Toki, T., Wang, D. T., Yoshinaga, M. Y., Arnold, G. L., Ashi, J., Case, D. H., Feseker, T., Hinrichs, K.-U., Ikegawa, Y., Ikehara, M., Kallmeyer, J., Kumagai, H., Lever, M. A., Morita, S., Nakamura, K., Nakamura, Y., Nishizawa, M., Orphan, V. J., Røy, H., Schmidt, F., Tani, A., Tanikawa, W., Terada, T., Tomaru, H., Tsuji, T., Tsunogai, U., Yamaguchi, Y. T., and Yoshida, N.: Deep-biosphere methane production stimulated by geofluids in the Nankai accretionary complex, Sci. Adv., 4, eaao4631, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao4631, 2018.

Inagaki, F., Hinrichs, K.-U., Kubo, Y., Bowles, M. W., Heuer, V. B., Hong, W.-L., Hoshino, T., Ijiri, A., Imachi, H., Ito, M., Kaneko, M., Lever, M. A., Lin, Y.-S., Methé, B. A., Morita, S., Morono, Y., Tanikawa, W., Bihan, M., Bowden, S. A., Elvert, M., Glombitza, C., Gross, D., Harrington, G. J., Hori, T., Li, K., Limmer, D., Liu, C.-H., Murayama, M., Ohkouchi, N., Ono, S., Park, Y.-S., Phillips, S. C., Prieto-Mollar, X., Purkey, M., Riedinger, N., Sanada, Y., Sauvage, J., Snyder, G., Susilawati, R., Takano, Y., Tasumi, E., Terada, T., Tomaru, H., Trembath-Reichert, E., Wang, D. T., and Yamada, Y.: Exploring deep microbial life in coal-bearing sediment down to ∼ 2.5 km below the ocean floor, Science, 349, 420–424, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa6882, 2015.

IPCC 2006: IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, edited by: Eggleston, H. S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., and Tanabe, K., IGES, Japan, ISBN 4-88788-032-4, https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/pdf/0_Overview/V0_0_Cover.pdf (last access: 2 December 2025), 2006.

Jautzy, J. J., M.J.Douglas, P., Xie, H., M.Eiler, J., and D.Clark, I.: CH4 isotopic ordering records ultra-slow hydrocarbon biodegradation in the deep subsurface, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 562, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2021.116841, 2021.

Jiang, W., Liu, Q., Li, J., Li, Y., Liu, W., Liu, X., Zhang, H., Peng, P., and Xiong, Y.: Deciphering the origin and secondary alteration of deep natural gas in the Tarim basin through paired methane clumped isotopes, Mar. Pet. Geol., 160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2023.106614, 2024.

Kim, J.-H., Martini, A. M., Ono, S., Lalk, E., Ferguson, G., and McIntosh, J. C.: Clumped and conventional isotopes of natural gas reveal basin burial, denudation, and biodegradation history, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 361, 133–151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2023.10.017, 2023.

Krause, S. J. E., Liu, J., D.Young, E., and Treude, T.: Δ13CH3D and Δ12CH2D2 signatures of methane aerobically oxidized by Methylosinus trichosporium with implications for deciphering the provenance of methane gases, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 593, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117681, 2022.

Labidi, J., Young, E. D., Giunta, T., Kohl, I. E., Seewald, J., Tang, H., Lilley, M. D., and Früh-Green, G. L.: Methane thermometry in deep-sea hydrothermal systems: Evidence for re-ordering of doubly-substituted isotopologues during fluid cooling, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 288, 248–261, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2020.08.013, 2020.

Labidi, J., McCollom, T. M., Giunta, T., Sherwood Lollar, B., Leavitt, W. D., and Young, E. D.: Clumped Isotope Signatures of Abiotic Methane: The Role of the Combinatorial Isotope Effect, J. Geophys. Res., 129, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JB028194, 2024.

Lalk, E., Pape, T., Gruen, D. S., Kaul, N., Karolewski, J. S., Bohrmann, G., and Ono, S.: Clumped methane isotopologue-based temperature estimates for sources of methane in marine gas hydrates and associated vent gases, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 327, 276–297, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2022.04.013, 2022.

Lalk, E., Seewald, J. S., Bryndzia, L. T., and Ono, S.: Kilometer-scale Δ13CH3D profiles distinguish end-member mixing from methane production in deep marine sediments, Org. Geochem., 181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2023.104630, 2023.

Lalk, E., Velez, A., and Ono, S.: Methane Clumped Isotopologue Variability from Ebullition in a Mid-latitude Lake, ACS Earth Space Chem., https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.3c00282, 2024.

Lan, X., Basu, S., Schwietzke, S., Bruhwiler, L. M. P., Dlugokencky, E. J., Michel, S. E., Sherwood, O. A., Tans, P. P., Thoning, K., Etiope, G., Zhuang, Q., Liu, L., Oh, Y., Miller, J. B., Pétron, G., Vaughn, B. H., and Crippa, M.: Improved Constraints on Global Methane Emissions and Sinks Using δ13C-CH4, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles, 35, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GB007000, 2021.

Li, J., Chiu, B. K., Piasecki, A. M., Feng, X., Landis, J. D., Marcum, S., Young, E. D., and Leavitt, W. D.: The evolution of multiply substituted isotopologues of methane during microbial aerobic oxidation, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 381, 223–238, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2024.06.032, 2024.

Li, J., Ash, J. L., Cobban, A., Kubik, B. C., Rizzo, G., Thompson, M., Guibourdenche, L., Berger, S., Morra, K., Lin, Y., Mueller, E. P., Masterson, A. L., Stein, R., Fogel, M., Torres, M. A., Feng, X., Holden, J. F., Martini, A., Welte, C. U., Jetten, M., Young, E. D., and Leavitt, W. D.: The clumped isotope signatures of multiple methanogenesis metabolisms, Env. Sci Technol, 59, 13798–13810, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5c03255, 2025a.

Li, J., Liu, Q., Jiang, W., Li, Y., Shuai, Y., and Xiong, Y.: Tracing the Contribution of Abiotic Methane in Deep Natural Gases From the Songliao Basin, China Using Bulk Isotopes and Methane Clumped Isotopologue 12CH2D2, Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems, 26, e2024GC011705, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GC011705, 2025b.

Lin, Y.-T., Rumble, D., Young, E. D., Labidi, J., Tu, T.-H., Chen, J.-N., Pape, T., Bohrmann, G., Lin, S., Lin, L.-H., and Wang, P.-L.: Diverse Origins of Gases From Mud Volcanoes and Seeps in Tectonically Fragmented Terrane, Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems, 24, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GC010791, 2023.

Liu, J., Harris, R. L., Ash, J. L., Ferry, J. G., Krause, S. J. E., Labidi, J., Prakash, D., Sherwood Lollar, B., Treude, T., Warr, O., and Young, E. D.: Reversibility controls on extreme methane clumped isotope signatures from anaerobic oxidation of methane, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 348, 165–186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2023.02.022, 2023.

Liu, J., Treude, T., Abbasov, O. R., Baloglanov, E. E., Aliyev, A. A., Harris, C. M., Leavitt, W. D., and Young, E. D.: Clumped isotope evidence for microbial alteration of thermogenic methane in terrestrial mud volcanoes, Geology, 52, 22–26, https://doi.org/10.1130/G51667.1, 2024a.

Liu, Q. and Liu, Y.: Clumped-isotope signatures at equilibrium of CH4, NH3, H2O, H2S and SO2, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 175, 252–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2015.11.040, 2016.

Liu, Q., Li, J., Jiang, W., Li, Y., Lin, M., Liu, W., Shuai, Y., Zhang, H., Peng, P., and Xiong, Y.: Application of an absolute reference frame for methane clumped-isotope analyses, Chem. Geol., 646, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2024.121922, 2024b.

Lopes, J. C., Matos, L. F. de, Harper, M. T., Giallongo, F., Oh, J., Gruen, D., Ono, S., Kindermann, M., Duval, S., and Hristov, A. N.: Effect of 3-nitrooxypropanol on methane and hydrogen emissions, methane isotopic signature, and ruminal fermentation in dairy cows, J. Dairy Sci., 99, 5335–5344, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2015-10832, 2016.

Ma, Q., Wu, S., and Tang, Y.: Formation and abundance of doubly-substituted methane isotopologues (13CH3D) in natural gas systems, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 72, 5446–5456, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2008.08.014, 2008.

Menoud, M., Veen, C. van der, Fernandez, J., Semra, B., Lowry, D., France, J., Fisher, R., Maazallahi, H., Korbeñ, P., Schmidt, M., Stanisavljeviæ, M., Necki, J., Łakomiec, P., Rinne, J., Defratyka, S., Yver-Kwok, C., Vinkovic, K., Andersen, T., Chen, H., and Röckmann, T.: European Methane Isotope Database Coupled with a Global Inventory of Fossil and Non-Fossil ä13C- and ä2H-CH4 Source Signature Measurements: V2.0.0, Utrecht Univ. [data set], https://doi.org/10.24416/UU01-YP43IN, 2022a.

Menoud, M., van der Veen, C., Lowry, D., Fernandez, J. M., Bakkaloglu, S., France, J. L., Fisher, R. E., Maazallahi, H., Stanisavljević, M., Nęcki, J., Vinkovic, K., Łakomiec, P., Rinne, J., Korbeń, P., Schmidt, M., Defratyka, S., Yver-Kwok, C., Andersen, T., Chen, H., and Röckmann, T.: New contributions of measurements in Europe to the global inventory of the stable isotopic composition of methane, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 14, 4365–4386, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-4365-2022, 2022b.

Mroz, E. J., Alei, M., Cappis, J. H., Guthals, P. R., Mason, A. S., and Rokop, D. J.: Detection of multiply deuterated methane in the atmosphere, Geophys. Res. Lett., 16, 677–678, https://doi.org/10.1029/GL016i007p00677, 1989.

Nisbet, E. G., Manning, M. R., Dlugokencky, E. J., Fisher, R. E., Lowry, D., Michel, S. E., Myhre, C. L., Platt, S. M., Allen, G., Bousquet, P., Brownlow, R., Cain, M., France, J. L., Hermansen, O., Hossaini, R., Jones, A. E., Levin, I., Manning, A. C., Myhre, G., Pyle, J. A., Vaughn, B. H., Warwick, N. J., and White, J. W. C.: Very Strong Atmospheric Methane Growth in the 4 Years 2014–2017: Implications for the Paris Agreement, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles, 33, 318–342, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GB006009, 2019.

Nothaft, D. B., Templeton, A. S., Rhim, J. H., Wang, D. T., Labidi, J., Miller, H. M., Boyd, E. S., Matter, J. M., Ono, S., Young, E. D., Kopf, S. H., Kelemen, P. B., and Conrad, M. E.: Geochemical, Biological, and Clumped Isotopologue Evidence for Substantial Microbial Methane Production Under Carbon Limitation in Serpentinites of the Samail Ophiolite, Oman, J. Geophys. Res., 126, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JG006025, 2021.

Ojeda, L., Etiope, G., Jimenez-Gavilan, P., Martonos, I. M., Rockmann, T., Popa, M. E., Sivan, M., Castro-Gamez, A. F., Benavente, J., and Vadillo, I.: Combining methane clumped and bulk isotopes, temporal variations in molecular and isotopic composition, and hydrochemical and geological proxies to understand methane's origin in the Ronda peridotite massifs (Spain), Chem. Geol., 642, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2023.121799, 2023.

Ono, S., Wang, D. T., Gruen, D. S., Sherwood Lollar, B., Zahniser, M. S., McManus, B. J., and Nelson, D. D.: Measurement of a Doubly Substituted Methane Isotopologue, 13CH3D, by Tunable Infrared Laser Direct Absorption Spectroscopy, Anal. Chem., 86, 6487–6494, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac5010579, 2014.

Ono, S., Jeemin H. Rhim, Danielle S. Gruen, Heidi Taubner, Martin Kolling, and Gunter Wegener: Clumped isotopologue fractionation by microbial cultures performing the anaerobic oxidation of methane, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 293, 70–85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2020.10.015, 2021.

Pataki, D. E.: Seasonal cycle of carbon dioxide and its isotopic composition in an urban atmosphere: Anthropogenic and biogenic effects, J. Geophys. Res., 108, 4735, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JD003865, 2003.

Prokhorov, I. and Mohn, J.: CleanEx: A Versatile Automated Methane Preconcentration Device for High-Precision Analysis of 13CH4, 12CH3D, and 13CH3D, Anal. Chem., 94, 9981–9986, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.2c01949, 2022.

Rhim, J. H. and Ono, S.: Combined carbon, hydrogen, and clumped isotope fractionations reveal differential reversibility of hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in laboratory cultures, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 335, 383–399, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2022.07.027, 2022.

Röckmann, T., Popa, M. E., Krol, M. C., and Hofmann, M. E. G.: Statistical clumped isotope signatures, Sci. Rep., 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31947, 2016.

Rumble, D., Ash, J. L., Wang, P.-L., Lin, L.-H., Lin, Y.-T., and Tu, T.-H.: Resolved measurements of 13CDH3 and 12CD2H2 from a mud volcano in Taiwan, J. Asian Earth Sci., 167, 218–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2018.03.007, 2018.

Safi, E., Arnold, T., and Rennick, C.: Fractionation of Methane Isotopologues during Preparation for Analysis from Ambient Air, Anal. Chem., 96, 6139–6147, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.3c04891, 2024.