the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Global ocean surface heat fluxes derived from the maximum entropy production framework accounting for ocean heat storage and Bowen ratio adjustments

Yong Yang

Jingfeng Wang

Wenxin Zhang

Gang Zhao

Weiguang Wang

Lei Cheng

Lu Chen

Hui Qin

Zhanzhang Cai

Ocean evaporation, represented by latent heat flux (LE), plays a crucial role in global precipitation patterns, water cycle dynamics, and energy exchange processes. However, existing bulk methods for quantifying ocean evaporation are associated with considerable uncertainties. The maximum entropy production (MEP) theory provides a novel framework for estimating surface heat fluxes, but its application over ocean surfaces remains largely unvalidated. Given the substantial heat storage capacity of the deep ocean, which can create temporal mismatches between variations in heat fluxes and radiation, it is crucial to account for heat storage when estimating heat fluxes. This study derived global ocean heat fluxes using the MEP theory, incorporating the effects of heat storage and adjustments to the Bowen ratio (the ratio of sensible heat to latent heat). We utilized multi-source data from seven auxiliary turbulent flux datasets and 129 globally distributed buoy stations to refine and validate the MEP model. The model was first evaluated using observed data from buoy stations, and the Bowen ratio formula that most effectively enhanced the model performance was identified. By incorporating the heat storage effect and adjusting the Bowen ratio within the MEP model, the accuracy of the estimated heat fluxes was significantly improved, achieving an R2 of 0.99 (regression slope: 0.97) and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 4.7 W m−2 compared to observations. The improved MEP method successfully addressed the underestimation of LE and the overestimation of sensible heat by the original model, providing new global estimates of LE at 93 W m−2 and sensible heat at 12 W m−2 for the annual average from 1988–2017. Compared to the 129 buoy stations, the MEP-derived global LE dataset achieved the highest accuracy, with a mean error (ME) of 1.3 W m−2, an RMSE of 15.9 W m−2, and a Kling–Gupta efficiency (KGE) of 0.89, outperforming four major long-term global heat flux datasets, including J-OFURO3, ERA5, MERRA-2, and OAFlux. Analysis of long-term trends revealed a significant increase in global ocean evaporation from 1988–2010 at a rate of 3.58 mm yr−1, followed by a decline at −2.18 mm yr−1 from 2010–2017. This dataset provides a new benchmark for the ocean surface energy budget and is expected to be a valuable resource for studies on global ocean warming, sea surface–atmosphere energy exchange, the water cycle, and climate change. The 0.25° monthly global ocean heat flux dataset based on the maximum entropy production method (GOHF-MEP) for 1988–2017 is publicly accessible at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26861767.v2 (Yang et al., 2024).

- Article

(9601 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2209 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The ocean system plays a pivotal role in regulating the global climate by receiving and redistributing heat and freshwater, thereby influencing Earth's energy balance and the dynamics of the water cycle (Li et al., 2023; Von Schuckmann et al., 2023; Marti et al., 2022; Johnson and Lyman, 2020). A key component in this system is ocean evaporation, which accounts for approximately 86 % of atmospheric water vapor, being the primary driver of the global hydrological cycle (Yu, 2011). As climate change warms the ocean, evaporation rates are expected to rise, potentially intensifying the global hydrological cycle (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). This intensification could alter precipitation patterns, affecting regional water availability and freshwater ecosystems (Konapala et al., 2020; Roderick et al., 2014). Therefore, precise estimation of ocean evaporation is critical to understand and quantify the global energy and water budget (Iwasaki et al., 2014).

Existing methods for calculating surface latent heat (LE) and sensible heat flux (H) rely on bulk transfer formulations, which require extensive input variables and parameterizations, such as temperature gradients, humidity gradients, wind speeds, and transfer coefficients (Fairall et al., 1996; Andreas et al., 2008). Although widely used, these bulk methods encounter significant limitations primarily due to challenges in accurately parameterizing and empirically deriving transfer coefficients (Zeng et al., 1998; Robertson et al., 2020). These methods heavily depend on assumptions regarding atmospheric stability and boundary layer dynamics, which may not consistently apply across diverse and complex environmental conditions (Fairall et al., 2003; Andreas et al., 2013). Furthermore, uncertainties in estimating turbulent transfer coefficients can lead to substantial errors in the estimation of latent heat flux. The high demands for parameterization and challenges in data acquisition contribute to considerable uncertainties when implementing bulk methods for calculations. While numerous energy balance-based algorithms have been developed to estimate global terrestrial evapotranspiration (Wang and Dickinson, 2012; Yang et al., 2023), their application to ocean surface heat flux estimation remains limited. Therefore, proposing an innovative method for estimating ocean surface heat flux based on surface energy balance could yield significant theoretical and practical implications. Such an approach could serve as a valuable complement to existing bulk methods and their associated datasets, providing a fresh methodological perspective for quantifying ocean heat flux. This advancement would not only enhance our ability to estimate ocean energy fluxes with greater accuracy but also deepen our understanding of their role in the global energy and water cycles.

The maximum entropy production (MEP) model, an energy-balance-based approach, has recently emerged as a novel method for simulating surface heat fluxes. Developed from Bayesian probability theory and information theory, the MEP prioritizes the most probable partitioning of radiation fluxes (Wang and Bras, 2011). The MEP model has been rigorously validated across diverse surface types and varying degrees of surface wetness (Wang et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022, 2023). Notably, the MEP model requires fewer input variables – net radiation, surface temperature, and specific humidity – yet it provides accurate estimates of LE, H, and ground heat fluxes simultaneously. Unlike bulk methods (Fairall et al., 2003), which rely on wind speed, temperature gradient, and humidity gradient, the MEP model satisfies the energy balance constraint without these dependencies. This characteristic enhances its applicability and robustness across diverse environmental conditions. However, the previous application of the MEP model over ocean surfaces has revealed significant limitations, including notable underestimations of latent heat and overestimations of H (Huang et al., 2017). The global multi-year averaged LE estimated by the MEP model indicated a value around 58 W m−2, much lower than the range of 92–109 W m−2 reported by remote sensing or reanalysis-based products. Conversely, MEP estimated an averaged H of approximately 28 W m−2, substantially higher than the 6–18 W m−2 range reported in other studies. These discrepancies highlight substantial uncertainties in applying the MEP model to oceanic energy partitioning, highlighting the urgent need for further refinement and rigorous validation. These substantial errors in MEP-estimated oceanic fluxes may be attributed to the lack of consideration of heat storage effects. The significant impact of heat storage in deep ocean water can introduce substantial bias in estimating seasonal evaporation rates when using the Penman combination-based method (McMahon et al., 2013; Bai and Wang, 2023). For instance, deep-water bodies typically store heat during the spring and release it in the fall, which can lead to overestimation of evaporation in the summer and underestimation in the fall if changes in heat storage are not accounted for (Zhao and Gao, 2019; Morton, 1994). Therefore, when estimating heat fluxes using the Bowen ratio (Bo, defined as the ratio of H to LE) energy-budget-based method (including the MEP method), it is essential to incorporate heat storage effects to ensure accurate partitioning of available energy.

Bo is crucial for understanding the global ocean energy partitioning process (Hicks and Hess, 1977). In the context of the energy-balance-based MEP model, the significant overestimation of Bo suggests that focusing on this ratio can enhance our understanding of energy partitioning dynamics (Andreas and Cash, 1996). Studies have highlighted that the actual Bowen ratio over ocean surfaces (Boa) often diverges from the equilibrium Bowen ratio () observed under ideal conditions where the air is saturated with water vapor. The Boa may deviate significantly from under non-equilibrium conditions, which are typical in most environments (Jo et al., 2002; Andreas et al., 2013), posing challenges in establishing a robust relationship between Boa and (Liu and Yang, 2021). Therefore, developing an accurate –Boa relationship is crucial for refining the energy partitioning process in the MEP model. The advancement of buoy observation networks has provided compelling evidence for validating ocean heat fluxes and has become crucial in assessing their associated uncertainties (Bourras, 2006; Smith et al., 2011; Bentamy et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2022). This study utilizes the energy-balance-based MEP method to estimate ocean evaporation, introducing a novel approach to redistributing surface energy budgets and offering a streamlined parameterization scheme distinct from conventional bulk methods used for estimating ocean heat fluxes. In contrast to existing approaches that used reanalysis-based schemes (e.g., NCEP, ECMWF, and GEOS) and their associated parameterizations to estimate LE, this study employs satellite observations to directly estimate ocean heat fluxes, thereby minimizing error propagation associated with the model structures and assimilation schemes.

Current global ocean surface heat flux datasets can be classified into five categories based on their deriving approaches (Tang et al., 2023): remote-sensing-based (e.g., J-OFURO3), atmospheric-reanalysis-based (e.g., ERA5), machine-learning-based (e.g., OHFv2), in situ-based (e.g., NOC), and hybrid-based (e.g., OAFlux) approaches. Compared to terrestrial flux products, these ocean flux products generally have a coarser spatial resolution ranging from 0.25 to 1.875°. Recent studies have conducted comprehensive assessments of global ocean heat flux datasets regarding their accuracy and error characteristics across spatial and temporal scales (Bentamy et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2023). However, substantial discrepancies remain among these datasets, particularly in terms of spatial patterns, annual means, and interannual variabilities. Therefore, developing a new global dataset using the innovative method could advance our understanding of deriving algorithms, improve temporal and spatial coverage of flux variables with a higher accuracy, and provide alternative reference to assess ocean surface heat fluxes in various applications. The primary objectives of this study are as follows: (1) to develop and validate the MEP approach for estimating ocean heat fluxes using observations from 129 stations, (2) to investigate the impact of heat storage on ocean energy allocation and the influence of the Bowen ratio on energy partitioning for heat flux estimations, and (3) to produce a MEP-derived ocean heat flux product (spatial resolution: 0.25°; temporal coverage: 1988–2017) and present its spatiotemporal patterns.

2.1 Components of ocean surface energy balance

The global ocean energy balance equation is as follows (Meehl, 1984; Wang et al., 2021):

where Rn, Rns, and Rnl are net radiation, net shortwave radiation (the difference of incoming radiation and reflected solar radiation ), and net longwave radiation (the difference of incoming longwave radiation and outgoing longwave radiation ), respectively; H is sensible heat, LE is latent heat; and G is the heat flow through the surface. Unlike terrestrial surfaces, the energy balance equation for the ocean surface accounts for distinct energy exchange processes, including the impact of seawater mixing and dynamics on energy transfer. For the ocean surface, the flux term G has two components:

where Gt is the change in the ocean heat content (ΔOHC, or heat storage), and Gv is the lateral heat transported by ocean currents and other processes. The Gt can be quantified as the vertical integration of temperature profile in a column of depth (Meehl, 1984, Li et al., 2023). Both the heat storage and the ocean heat transport Gv are difficult to quantify, which requires large masses of hydrographic variables and performing integrations at different depths. Since the lateral heat transport by ocean currents is zero at the global scale (Wang et al., 2021), G can be regarded as equivalent to the change in ocean heat content or heat storage at the global level. For the consistency throughout the paper, this study will consider the concept of G flux as equivalent to the changes in the heat storage.

2.2 The maximum entropy production theory

2.2.1 The original MEP model

The MEP model simulates ocean surface heat fluxes using input variables of net radiation (Rn), surface skin temperature (Ts), and surface specific humidity (qs) under the constraint of the surface energy balance. The latent heat, sensible heat, and surface thermal energy flux (Q) are calculated as

where B(σ) is the reciprocal Bowen ratio, σ is a dimensionless parameter that characterizes the phase change at the ocean surface, λ (J kg−1) is the latent heat of vaporization of liquid surface, cp () is the specific heat of air under constant pressure, and Rv (461 ) is the gas constant of water vapor. I0 is the “apparent thermal inertia” of air and describes the turbulent transport process of the boundary layer based on the Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (MOST) (Wang and Bras, 2010). Is is the thermal inertia of the ocean surface () and can be parameterized as (with density ρ, the specific heat c), which represents the physical property of the surface ( for water surface and for ice surface).

Over the sea ice surface, assumed to be saturated, the specific humidity qs can be derived as a function of surface temperature Ts using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation (El Sharif et al., 2019; Shaman and Kohn, 2009).

where ε (=0.622) represents the ratio of the molecular weight of water vapor to that of dry air, es(Ts) denotes the saturation vapor pressure at temperature Ts, e0 is the saturation vapor pressure at the reference temperature T0 (273.15 K), and P is the atmospheric pressure (mbar).

2.2.2 Specific improvements on the MEP model

According to the MEP theory, the net solar radiation (Rns) entering the water surface medium is absorbed by the water body, with the allocable radiation flux denoted as (Eq. 6). Consequently, the expression for ocean heat uptake (heat storage) is derived as . While this theory has received preliminary validation in shallower water bodies, such as lake surfaces (Wang et al., 2014), its applicability to deeper water bodies with larger heat storage capacities in ocean surfaces requires further evaluation. This study introduced two key hypotheses: (1) the substantial heat storage capacity of the ocean could exert a significant influence on seasonal latent and sensible fluxes, potentially introducing bias to the MEP equations, and (2) the notable underestimation of latent heat flux and overestimation of sensible heat flux by the MEP model point to a significant deviation from Bowen's ratio formula, necessitating a reasonable correction. To address this, the study proposed two approaches for enhancing the MEP formulas: (1) considering the impact of heat storage in the MEP's energy balance equation and (2) adjusting the theoretical equilibrium Bowen ratio within the MEP model. This can be specifically represented as follows:

where is the equilibrium Bowen ratio, which denotes the theoretical ratio of sensible heat flux to latent heat flux when the surface and the atmosphere are in equilibrium regarding water vapor. The corresponding evaporation at this condition is known as equilibrium evaporation (defined as the water vapor evaporating from a saturated surface into a saturated atmosphere). To accurately predict actual evaporation, a reliable functional relationship needs to be established to predict Boa from . Empirical studies have introduced coefficients to correlate to Boa under diverse environmental circumstances; for instance, the Priestley–Taylor coefficient was expressed as (Priestley and Taylor, 1972)

Further studies have led to the emergence of more updated empirical coefficients. Hicks and Hess (1977) estimated the actual Bowen ratio as by aligning it with direct observations of the fluxes. Yang and Roderick (2019) deduced an empirical coefficient of 0.24 and formulated it as by fitting the Bowen ratio and surface temperature data across the global ocean surface. Furthermore, Liu and Yang (2021) derived a new equation as based on the atmospheric boundary layer model. Given their favorable spatial applicability and representativeness, this study opted to utilize these four Boa formulas to refine the MEP model and assess their suitability. The revised reciprocal actual Bowen ratio was represented as

where B(σ)a1∼B(σ)a4 represents the four empirical Bowen ratio formulas for comparisons in this study. Thus, the workflow of the improved MEP model was conducted by replacing the original B(σ) with the corrected B(σ)a and then combining Eqs. (5), (7)–(9), and (14) into the MEP energy balance equation considering heat storage (Eq. 10), ultimately leading to the determination of latent and sensible heat flux.

2.3 Sensitivity analysis

To quantify the influence of input variables in the MEP model on evaporation estimate at the ocean surface, the sensitivity coefficient (S) was computed as (Beven, 1979; Isabelle et al., 2021)

where Si represents the sensitivity coefficient of LE to each variable xi. The magnitude of Si reflects the degree of impact of the variable's changes on LE; a larger absolute value indicates a greater influence of the variable on LE. A positive value signifies a positive correlation between evaporation and the variable's changes, while a negative value indicates a negative correlation. For example, a sensitivity coefficient of 0.5 represents that a 10 % increase in the variable would result in a 5 % increase in LE. The sensitivity levels can be categorized into four classes based on the absolute value (Lenhart et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2010): indicates very high sensitivity, denotes high sensitivity, reflects moderate sensitivity, and suggests negligible sensitivity.

2.4 Data fusion methods

To drive the improved MEP model with high-quality input data, this study aims to obtain a heat storage dataset with optimal accuracy. The accuracy of the heat storage dataset was assessed using three approaches: (1) an individual dataset, (2) a fused dataset generated using the Bayesian three-cornered hat (BTCH) method (He et al., 2020), and (3) an ensemble means obtained by the arithmetic average (AA) method. Previous studies have demonstrated that the BTCH method effectively quantifies uncertainties across diverse datasets and improves accuracy by integrating multiple datasets without requiring prior knowledge (Long et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021; Duan et al., 2024). A recent study further evaluated various data fusion methods, including BTCH and the AA methods, for addressing uncertainties in global evapotranspiration estimates derived from different datasets. The findings revealed that while both BTCH and AA are effective in identifying lower-quality evapotranspiration datasets, their ability to consistently produce higher-accuracy datasets remains uncertain and, in some cases, may even degrade the overall accuracy (Shao et al., 2022). The performance of these fusion methods is highly sensitive to the selection of input datasets. For instance, the AA method is particularly susceptible to the influence of lower-quality datasets, especially when the sample size is small. Similarly, the performance of BTCH diminishes as the error covariance among the included datasets increases. Consequently, following a comparative analysis of the accuracy of individual, BTCH, and AA fusion datasets, this study selected the optimal heat storage dataset to drive the MEP model. Since BTCH is not the primary focus of this study, detailed method descriptions can be found in He et al. (2020).

3.1 Input data for MEP model

The performance of both the original and improved maximum entropy production (MEP) models was evaluated using observed data from in situ buoy stations, as described in Sect. 3.2. The optimal empirical Bowen ratio formula for the MEP model was then determined by multi-site assessments. Subsequently, the improved MEP model was applied to estimate global heat fluxes using long-term remote sensing data, as detailed in Sects. 3.3 and 3.4. Specifically, the input variables of net radiation, heat storage, and sea surface temperature driving the improved MEP model were derived from the J-OFURO3 dataset, spanning 1988–2017 with a spatial resolution of 0.25°, as outlined in Sect. 4.3.

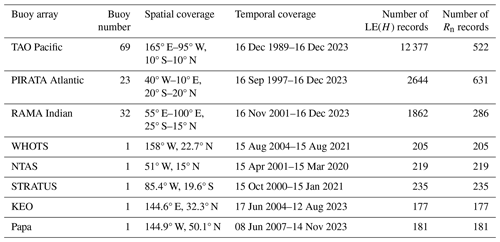

3.2 In situ buoy observations

A total of 129 in situ buoy sites were employed for ocean heat flux calculation and validation with MEP model and its modified version, as listed in Table 1. About 96 % of selected sites (124 of 129 all sites) were collected from the Global Tropical Moored Buoy Array (available at https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/, last access: December 2023), which consists of the TAO Pacific Ocean (69 buoys), PIRATA Atlantic Ocean (23 buoys), and RAMA Indian Ocean (32 buoys). Other sites include the Project WHOTS–WHOI Hawaii Ocean Time-series Station (available at https://uop.whoi.edu/ReferenceDataSets/whotsreference.html, last access: December 2023), Project NTAS – Northwest Tropical Atlantic Station and Project STRATUS (https://uop.whoi.edu/ReferenceDataSets/ntasreference.html, last access: December 2023) from the Upper Ocean Processes Group, and the KEO and Papa moorings from Pacific Ocean climate stations (https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/ocs/data/fluxdisdel/, last access: December 2023). For the availability of all buoy stations, refer to the “Data availability” section. The observational sites covered the spatial range of 25° S−50.1° N; the temporal range spans from December 1989 to December 2023. Observational meteorological variables and heat fluxes included the net longwave radiation, net shortwave radiation, sea surface skin temperature, specific humidity at 2 m height (if available, or computed as the function of sea surface temperature (SST) according to the Clausius–Clapeyron equation), latent heat flux, and sensible heat flux. Limited by the availability of longwave radiation observations, the net radiation had a relatively shorter time series length compared to latent and sensible heat fluxes. The surface air–sea fluxes of buoy observations were computed using the COARE 3.0b algorithm, which have been widely applied for flux estimations and validations (Tang et al., 2023; Bentamy et al., 2017; Fairall et al., 2003). All the selected original buoy observation (except for KEO and Papa sites) records were in monthly temporal resolution, and the original daily observations of KEO and Papa had been aggregated to monthly by a simple average method. The spatially distributed map of all selected sites is illustrated in Fig. S1 in the Supplement.

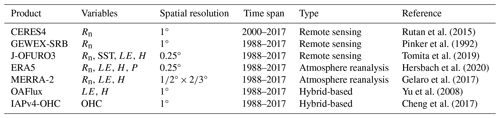

3.3 Global turbulent heat flux datasets for evaluations

This study evaluated and compared seven global turbulent heat flux products with observations, categorizing them into three types: remote-sensing-based, atmosphere-reanalysis-based, and hybrid-based (Table 2). These seven products encompassed monthly data spanning from 1988–2017, with spatial resolutions ranging from 0.25 to 1°. The criterion for dataset filtering prioritized products with relatively long time series, typically exceeding 15 years.

The Clouds and Earth's Radiant Energy Systems Synoptic Edition 4 A (CERES SYN1deg_Ed4 A, hereafter referred to as CERES4, available at https://ceres.larc.nasa.gov/data/, last access: December 2023) offers net radiation data, derived from clear-sky upward shortwave, downward shortwave, upward longwave, and downward longwave flux measurements (Wielicki et al., 1996; Rutan et al., 2015). Another remote-sensing-based radiation product, the Global Energy and Water Cycle Experiment–Surface Radiation Budget (GEWEX-SRB, available at https://asdc.larc.nasa.gov/project/SRB, last access: December 2023) (Pinker and Laszlo, 1992), in conjunction with CERES4, demonstrated good accuracy in retrieving Rn, as validated by six global observing networks (Liang et al., 2022).

The J-OFURO3 is the third-generation dataset developed by the Japanese Ocean Flux Data Sets with Use of the Remote Sensing Observations (J-OFURO) research project (available at https://search.diasjp.net/en/dataset/JOFURO3_V1_1, last access: October 2020) (Tomita et al., 2019). It calculated turbulent heat flux with the latest version of the COARE3.0 algorithm and provided datasets for Rn, LE, H, and SST in this study. Validation with in situ observations showed that J-OFURO3 offered a superior performance of latent heat compared to the other five satellite products from 2002–2013 (Tomita et al., 2019).

Two atmosphere reanalysis products include the fifth-generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) atmospheric Re-Analysis52 (ERA5, available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels-monthly-means?tab=overview, last access: December 2023) (Hersbach et al., 2020) and the Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications Version 2 (MERRA-2, available at https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/M2TMNXOCN_5.12.4/summary, last access: November 2018) (Gelaro et al., 2017). Both ERA5 and MERRA-2 products employed the bulk formula based on the MOST to calculate heat fluxes. Validation results from previous studies have demonstrated good consistency with buoy estimates regarding heat fluxes (Pokhrel et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020).

The OAFlux (available at https://oaflux.whoi.edu/, last access: November 2018), a hybrid-based product developed under the Objectively Analyzed Air–Sea Fluxes (OAFlux) project at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) (Yu et al., 2008), was utilized for comparisons with ocean heat fluxes derived from distinct methods. This product calculates fluxes based on the COARE3.0 bulk algorithm and employs a variational objective analysis to determine the optimal fitting of independent variables. Detailed descriptions on all utilized global turbulent heat flux products and their validation performances against buoy observations with reported studies are available in Tang et al. (2023).

3.4 Ocean heat content data

Remote sensing data for heat storage (G) were primarily derived from two categories: the first category included data obtained from the residual of the energy balance equation (), including J-OFURO3, ERA5, and MERRA-2; the second category was calculated from changes in ocean heat content (OHC). The ocean heat content data were obtained from the IAP OHC gridded analysis (IAPv4, available at http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/, last access: December 2023) dataset, covering an ocean depth of 0–6000 m (Cheng et al., 2017), and have been extensively utilized in global ocean heat analysis, ocean warming, and climate change studies (Li et al., 2023; Cheng et al., 2022, 2024). The delta OHC was calculated using the numerical differentiation method (Xu et al., 2019) as

where i denotes the OHC of the ith month. At the WHOTS site, this study compared the OHC changes at different depths with the observed G, derived as (Table S1 in the Supplement). Since the OHC variation from 0−100 m depth exhibited the smallest error with the observations, the data from 0−100 m depth range were chosen as the heat storage. This study assessed the suitability of G flux and ΔOHC for global evaporation estimations, with the aim of minimizing the errors introduced by input variable data in the MEP model.

This study evaluated the accuracy of all the variables (Rn, Ts, and G) using the aforementioned datasets on a global scale by comparing them against buoy observations (in Sect. 4.3), to optimize input accuracy for driving the MEP model. To maintain consistency in the analysis, this study resampled all products to 1° spatial resolution when comparing the Bowen ratio across multiple products. Nevertheless, when conducting site validations with buoy observations, the original resolution of the data was preserved to minimize uncertainty attributable to scale effects.

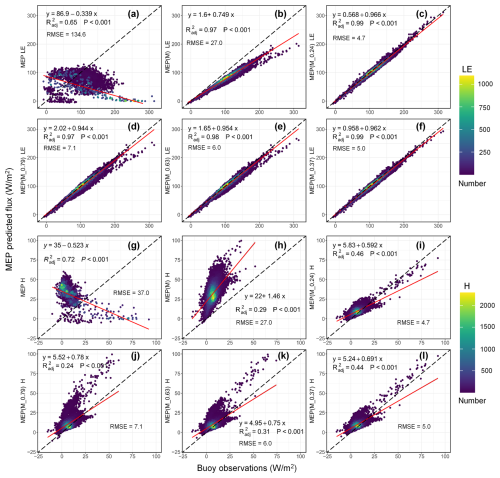

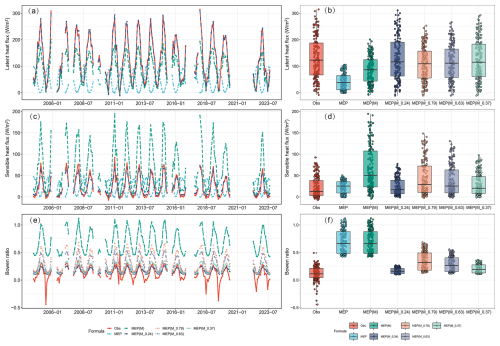

4.1 The new MEP model with heat storage and the revised Bowen ratio formulas

To demonstrate how the MEP model has been developed and improved, we show the comparisons of different MEP models in simulating heat fluxes across 129 global buoy stations (Fig. 1). Limited by the availability of RnL data, we used LE+H instead of the available energy (Rn−G), enabling the utilization of more observational records to verify the MEP model. The original MEP model (without considering heat storage) showed a significant negative correlation between LE and H (with R2 exceeding 0.65 as in Fig. 1a and c), with considerable errors, where the RMSE of LE was 134.6 W m−2 and that of H was 37 W m−2. After incorporating the influence of heat storage effects (represented as MEP_M, as depicted in Fig. 1b and h), the MEP-simulated LE showed a good consistency with buoy observations, with an R2 value of 0.97 and a reduced RMSE of 27 W m−2. However, the MEP_M method revealed a significant bias in the partitioning of LE and H from the available energy. Specifically, LE was underestimated by 25 % (regression slope=0.75), while H was overestimated by 46 % compared to observations. This finding agreed with previous research findings that equilibrium evaporation tended to underestimate actual evaporation from saturated surfaces by 20 %−30 % (Yang and Roderick, 2019; Philip, 1987). The significant difference between Boa and could exist as the equilibrium evaporation is considered the lower limit of actual evaporation from saturated surfaces (Priestley and Taylor, 1972). To address the deviation between Boa and , it is necessary to convert the equilibrium Bowen ratio into the actual Bowen ratio, allowing for a more reasonable and accurate allocation of surface energy budget.

Figure 1Scatter density plots of monthly latent heat flux (a–f) and sensible heat flux (g–l) derived by the original and modified MEP methods versus observations from 129 buoy stations (as in Table 1). (a) The original MEP method; (b) the modified MEP method considering the heat storage effect; (c) the modified MEP method considering both the heat storage and empirical Bowen ratio formula ; and (d–f) the modified MEP method considering both the heat storage and empirical Bowen ratio formulas , , and . Panels (g–l) are the same as (a–f) but for sensible heat flux.

After incorporating the effects of heat storage, four variants of the MEP model were developed by replacing with Boa derived from four different empirical formulas. These variants were defined as follows: M_0.24 (where ), M_0.79 (where ), M_0.63 (where ), and M_0.37 (where ). Adjusting the Bowen ratio significantly improved the accuracy of the energy flux estimates. The simulated LE exhibited strong agreement with observations, with all R2 exceeding 0.97 and RMSE ranging from 4.7 W m−2 (for M_0.24) to 7.1 W m−2 (for M_0.79), which was lower than that derived from (). Both M_0.79 and M_0.63 tended to underestimate LE, especially when LE exceeded 200 W m−2 (Fig. 1d and e). For the simulated H, the M_0.24 outperformed the other three, showing the smallest errors and highest R2.

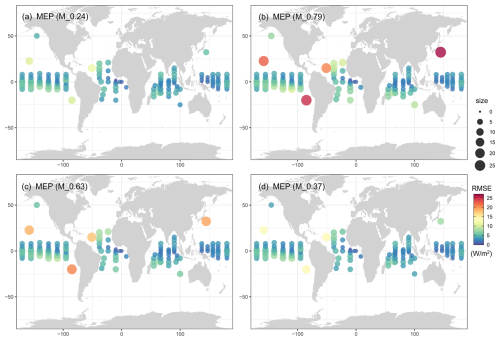

Figure 2Spatial distribution of RMSE values in the comparison between latent heat flux estimated by the improved MEP method (modified by four different Bowen ratio formulas) and buoy observations from 129 stations.

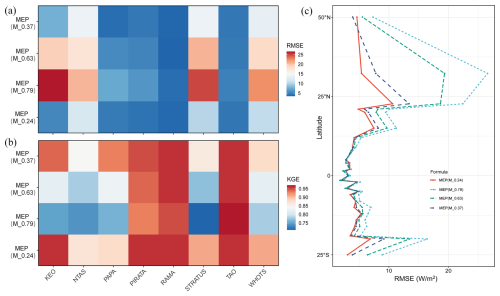

Specifically, the spatial patterns in simulated errors for the four variants of the MEP model were obtained (Fig. 2), along with the errors across different observational buoy arrays (Fig. 3). Overall, the four variants of the improved MEP models demonstrated relatively lower bias at low latitudes (10° S–10° N) but exhibited larger bias in higher-latitude regions (above 15° N), particularly at the KEO, WHOTS, and STRATUS buoy sites. Comparing the four formulas across varying latitudes, the M_0.24 formula exhibited the smallest RMSE (ranging from 3.6 to 12 W m−2) (Fig. 3c), while the M_0.79 formula showed the largest errors (RMSE ranging from 3.9 to 26.6 W m−2). This consistency was also evident in the Kling–Gupta efficiency (KGE) coefficient, with M_0.24 demonstrating superior performance in terms of accuracy, robustness, and adaptability. In terms of the M_0.24 formula, the prediction errors across observational arrays ranked as follows: RAMA < PIRATA < TAO/TRION < Papa < KEO <STRATUS < WHOTS < NTAS. The arrays with relatively larger RMSE (NTAS in the Atlantic Ocean, WHOTS, and STRATUS in the Pacific Ocean) may originate from the larger observed values of LE (Fig. S2).

Figure 3Comparisons between latent heat flux estimated by the improved MEP method using four empirical Bowen ratio formulas and the buoy observations from each buoy array in terms of RMSE (a), KGE value (b), and latitudinal means of RMSE (c). Latitudinal means are based on data from 129 available buoy sites.

4.2 Dynamics of heat fluxes and Bowen ratio between original and improved MEP model

To thoroughly investigate the role of heat storage in the partitioning of surface energy and its implications for the temporal dynamics of heat fluxes, we selected the KEO site for detailed analysis. This selection was based on the site's long-term observational records and notable variability in flux patterns, which offered an ideal context for a rigorous comparison of model-simulated error margins.

The improved MEP methods demonstrated comparable performance in estimating heat fluxes at the KEO site when compared with other 128 sites (Figs. 1 and S3), with the MEP (M_0.24) model exhibiting the most effective performance. Analysis of the time series data revealed significant variations in latent heat, sensible heat, and Bowen ratio (Fig. 4). In the original MEP theory, the estimated LE exhibited an opposite variation cycle (peak versus trough) compared to the observations. For instance, over a yearly period, the observed peak in LE occurred in January 2005 (269 W m−2) and the trough in June 2005 (6.9 W m−2). In contrast, the MEP simulated the peak in LE to occur in August 2005 (105 W m−2) and the trough in December 2004 (0.7 W m−2), resulting in a phase difference of 7 months for the peak and 6 months for the trough values. Sensible heat flux (Fig. 4b) showed similar phase differences: observed H peaked in January 2005 (79 W m−2) and reached its minimum in June 2005 (−3 W m−2), whereas MEP simulated H to peak in August 2005 (46 W m−2) and reach its minimum in December 2004 (0.6 W m−2), consistent with the pattern observed for LE. It was noteworthy that the original MEP model-simulated variations in LE and H align with Rn (Fig. S4), which was reasonable over land where the small G value can often be disregarded. However, over the ocean, the observed variations in Rn and LE do not align in terms of their cycles. The maximum Rn occurred in June 2004 (329 W m−2), and the minimum occurred in December 2004 (142 W m−2), with a 6-month delay in relation to the variations in LE. Specifically, the peak Rn corresponded to the trough of LE, and the trough Rn corresponded to the peak of LE. This delay indicated that the heat storage effect delayed the peak of LE and altered the seasonal variations in LE and H.

Figure 4The interannual variations (a, c and e) and variabilities (b, d, and f) in latent heat flux, sensible heat flux, and Bowen ratio at the KEO site from 17 June 2004 to 12 August 2023. The fluxes in the comparison include observations and the estimates from MEP using the original formula (MEP), the formula incorporating the ocean heat storage (MEP(M)), and four other formulas considering both ocean heat storage and adjustment of the Bowen ratio. Note that (a) and (c) only display results using MEP M_0.24 among all four empirical Bowen ratio formulas for clearer comparison.

For the patterns in the Bowen ratio, both the original MEP formula and the modified formulas exhibited consistent patterns with the observed values. The observed maximum Bowen ratio occurred in January 2005 (0.29) and the minimum in June 2005 (−0.4). However, the original MEP formula simulated a maximum of 1.01 and a minimum of 0.44, indicating a significant overestimation compared to the observed Bowen ratio. This discrepancy suggested that on the ocean surface, the available energy (Rn−G) was predominantly allocated to LE (Fig. S4). Among the four empirical formulas, M_0.24-simulated LE, H, and Bowen ratio values were closest to the observed values. The median of the observed Bowen ratio was 0.11, while the original MEP Bowen ratio was 0.66. Among the four modified Bowen ratio formulas (M_0.24, M_0.79, M_0.63, M_0.37), their median Bowen ratios were 0.15, 0.32, 0.27, and 0.19, respectively, with M_0.24 being the closest to the observed Bowen ratio.

Heat storage is crucial for the energy distribution process over the ocean surface. While the original MEP formulas have been effectively validated when applied to surfaces with shallow depths such as water and snow (Wang et al., 2014), they exhibit significant uncertainty when applied to the ocean surface. This discrepancy primarily arises from the fact that land is a non-transparent medium with relatively small heat storage values at monthly scales. Similarly, shallow water bodies also exhibit small heat storage values that can often be ignored. In the study by Wang et al. (2014), for example, two lakes with depths of 2 m (Lake Tämnaren) and 4 m (Lake Råksjö) still resulted in underestimated LE. However, for deeper lakes (generally>3 m depth), heat storage becomes significant and cannot be neglected (Zhao et al., 2016; Zhao and Gao, 2019). On deep ocean surfaces, with the most recent average depth estimate of 3682 m from NOAA satellite measurements, heat storage variations can influence depths up to 6000 m (Cheng et al., 2017). Therefore, the impact of heat storage was substantial and cannot be disregarded. In the original MEP theory, heat storage was not considered in the energy balance equation, where it was assumed that the net solar radiation (Rns) is absorbed by the ocean and . Then, the heat storage was obtained as . In this study, we compared the characteristics of MEP-derived G (Rns+Q) with the observed G flux (LE−H; Fig. S5). MEP-derived G showed a good correlation (R=0.96) and consistent trends with the observed values (Fig. S5a and b), ranging from −4 to 81 W m−2. However, MEP-calculated Q (ranged from −210 to −65 W m−2) exhibited a negative correlation with the observed G (which ranged from −386 to 200 W m−2). Both MEP-derived G and Q fluxes were significantly underestimated. Therefore, the prediction errors in LE and H originated from the inability to accurately quantify the heat storage. Hence, considering the influence of heat storage was crucial for accurately predicting LE and H over the ocean surface.

4.3 Evaluation of global radiation and heat storage flux

4.3.1 Evaluation of net radiation

After considering the effect of heat storage and the Bowen ratio, the improved MEP method demonstrated its high performance at the site scale. The results suggested that the improved MEP method held substantial promise for further application at a global scale. To facilitate this, we assessed the primary input variables of the improved MEP method (including Rn, G, and Ts) to identify datasets with the best accuracy.

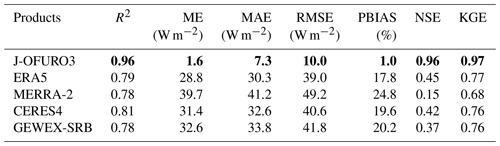

Table 3Evaluation of global monthly net radiation products against buoy observations.

Note that the evaluation period for all datasets is 1988–2017, except for CERES4, which spans from March 2000 to December 2017. ME is mean error, MAE is mean absolute error, PBIAS is the percentage bias, NSE is Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency, and KGE is Kling–Gupta efficiency. The best-performing statistics are indicated in bold type.

Net radiation, as the primary variable in the energy balance equation, significantly influenced the uncertainty of the MEP model (Huang et al., 2017). Selecting a reliable Rn product was essential for accurately estimating global latent and sensible heat fluxes. Previous studies have evaluated the available global ocean surface Rn datasets at a daily scale using observations from 68 moored buoy sites (Liang et al., 2022). In this study, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of current available monthly Rn products, including three remote-sensing-based products (CERES4, GEWEX-SRB, and JOFURO3) and two atmosphere-reanalysis-based products (ERA5 and MERRA-2) at 129 buoy sites. All products exhibited good consistency with buoy observations (Table 3 and Fig. S6), with R2 values greater than 0.78. In terms of RMSE, the error rankings for all products were J-OFURO3 (10 W m−2) < ERA5 (39.03 W m−2) < CERES4 (40.67 W m−2) < GEWEX-SRB (41.83 W m−2) < MERRA-2 (49.23 W m−2). It was evident that J-OFURO3 demonstrated the highest accuracy, as indicated by RMSE, Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), and KGE statistics. This result was also consistent with previous assessments of global Rn (Liang et al., 2022), emphasizing J-OFURO3 as the least erroneous among all individual products and superior to existing alternatives including CERES4, ERA5, MERRA-2, GEWEX-SRB, JRA55, OAFlux, and TropFlux.

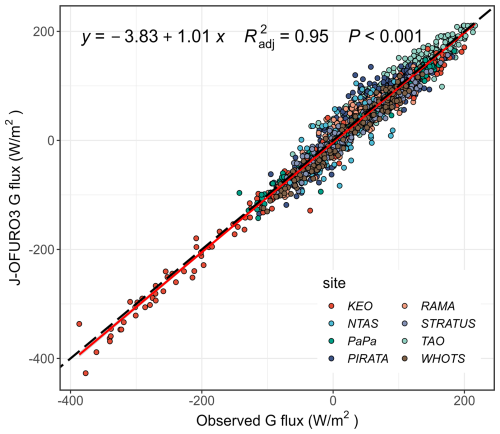

4.3.2 Evaluation of heat storage

The study underscored the importance of considering heat storage in simulating heat fluxes using the improved MEP model. For the first time, we assessed global heat storage using the J-OFURO3, ERA5, MERRA-2, and ΔOHC datasets. In addition to assessing these individual datasets, we investigated the potential for enhancing accuracy through data fusion methods. We employed the BTCH and AA method to fuse heat storage data and compared the accuracy between individual datasets and fused datasets (Table 4). The results revealed that while using the AA method (e.g., AA4) for fusion yields smaller errors compared to ERA5, MERRA-2, and ΔOHC, it still failed to achieve the accuracy of the J-OFURO3 product. Similarly, the BTCH method, despite fusing data from three or four sources, also does not match the accuracy of the J-OFURO3 method, as indicated by metrics of R2, RMSE, and KGE. The heat storage derived from J-OFURO3 data showed high consistency with observations (R2=0.95), as illustrated in Fig. 5 (spatial distribution of errors depicted in Fig. S7). Therefore, this study employed the heat storage data derived from the J-OFURO3 dataset as the input for the MEP model.

Figure 5Assessment of heat storage (G) flux derived from the remotely sensed J-OFURO3 dataset against buoy observations. Distinct colors represent data collected from different buoy arrays.

To ensure consistency with the radiation data source, the SST data from J-OFURO3 were utilized for Ts inputs, which were derived as the ensemble median from 12 global SST products (Tomita et al., 2019). Ultimately, the input variables including net radiation, heat storage, and sea surface temperature for driving MEP model were all determined from the J-OFURO3 dataset spanning from 1988–2017. Saturated specific humidity was computed as a function of SST and surface air pressure (from ERA5) using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation. The reliability of gridded data for the variables Rn, G, and Ts was simultaneously examined at an observational site (Fig. S8), where all three variables demonstrated high consistency with observed data from August 2004 to December 2017 (with R2>0.96), effectively capturing the monthly dynamics of Rn, G, and Ts.

Table 4Assessment of monthly heat storage between global remote sensing datasets and buoy observations.

Note: BTCH3-1(EMJ) represents the fusion of three products (ERA5, MERRA-2, and J-OFURO3) using the BTCH method; TCH3-2(EMO) represents the fusion of ERA5, MERRA-2, and OHC; BTCH4 represents the fusion of ERA5, J-OFURO3, MERRA-2, and OHC. AA denotes the simple arithmetic average (AA) method. AA2 (EM) means the ensemble mean of ERA5 and MERRA-2 using the AA method. AA3 (EMJ) means the ensemble mean of ERA5, MERRA-2, and J-OFURO3. AA4 (EMJO) means the ensemble mean of all products (ERA5, MERRA-2, J-OFURO3, and OHC). The evaluation period spans from 1988 to 2017, and the best-performing statistics are indicated in bold type.

4.4 Estimating long-term global ocean surface heat fluxes with the improved MEP model

4.4.1 New estimate of global latent and sensible heat fluxes

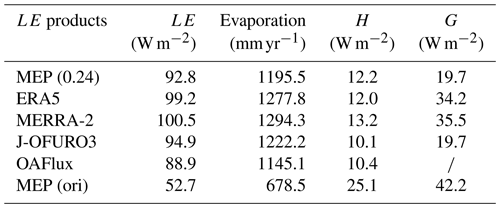

After identifying the optimal driving dataset, this study employed the best-performing improved MEP method (i.e., M_0.24), hereinafter referred to as MEP for simplicity, while the original MEP formula was denoted as MEP (ori) for global scale estimation, producing new estimations of latent and sensible heat fluxes for the period 1988–2017 (Table 5). The MEP model calculated the multi-year average LE as 92.87 W m−2 and the sensible heat flux as 12.27 W m−2 from 1988–2017. In comparison, LE ranged from 88.95 (OAFlux) to 100.54 W m−2 (MERRA-2), and H ranged from 10.17 (J-OFURO3) to 13.16 W m−2 (MERRA-2) for the other four products. The original MEP method yielded estimates of LE as 52.70 W m−2 and H as 25.07 W m−2, significantly underestimating LE and overestimating H compared to estimates from other products. As previously demonstrated (Sects. 4.1 and 4.2), the original MEP method overestimated G (42.20 W m−2) and exhibited notable deviations in the Bowen ratio. Therefore, the improved MEP method provided a more reasonable global estimation of LE and H.

Table 5Global area-averaged multi-annual mean estimates of latent heat flux.

Note that the period spans from 1988–2017. The MEP (0.24) denotes the improved MEP model, while MEP (ori) represents the original MEP model.

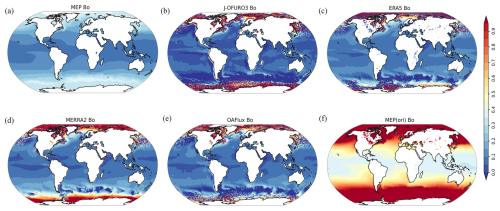

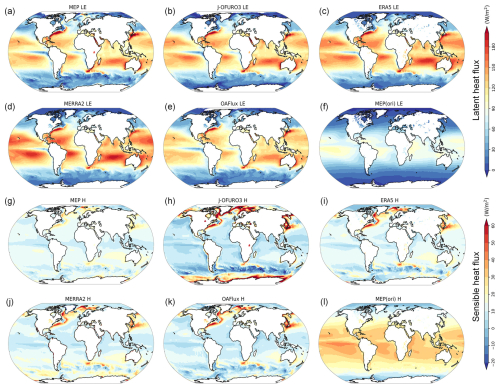

Regarding the global spatial pattern (Fig. 6), the MEP-derived latent heat exhibited higher values in low-latitude regions but significantly decreased at latitudes higher than 45° N or 45° S. The highest LE values were observed in the southern Indian Ocean near Australia, the Pacific and Atlantic regions near South America, and the Indian Ocean near southern Africa. The peak values were observed within western boundary current systems (ranged from 200 to 260 W m−2), including the Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic and the Kuroshio in the western North Pacific. Impacted by the variations in oceanic currents near the Equator, two general areas of higher LE have emerged (Yu, 2011), leading to notably low LE at the Equator (88 W m−2), peaking at ∼18° S at 132 W m−2 (Figs. 6 and 7). The MEP-estimated LE exhibited a similar spatial pattern with the other four products globally (Fig. 6), particularly resembling OAFlux between 15° S and 15° N (Fig. 7). Overall, for the region between 30° S and 30° N, the LE values were ranked as follows: OAFlux < MEP < J-OFURO3 < ERA5 < MERRA-2, which was consistent with the magnitude of available energy. For sensible heat, MEP-derived H closely resembled that of ERA5 and MERRA-2, with higher values predominantly occurring in two western boundary current systems: the southern Indian Ocean near the Australia area and the Arctic Ocean. The improved MEP method mitigated the issue of overestimating H in middle to high latitudes compared to its original form (Fig. 6l), resulting in a more realistic spatial pattern. In high latitudes, J-OFURO3 exhibited higher H values than MEP and other comparable products in the Northern Hemisphere, with negative values observed between 45 and 55° S. MEP generally estimated H within an intermediate range compared to other products, displaying a distribution that was more reasonable than that of J-OFURO3 product.

Figure 6Global spatial maps of annual mean latent heat flux (LE) and sensible heat flux (H) during 1988–2017. Panels (a–f) depict latent heat flux derived from the improved MEP method, J-OFURO3, ERA5, MERRA-2, OAFlux, and the original MEP method. Panels (g–l) show sensible heat flux from the same datasets.

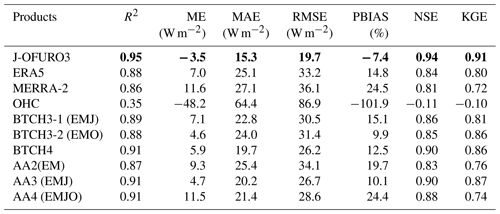

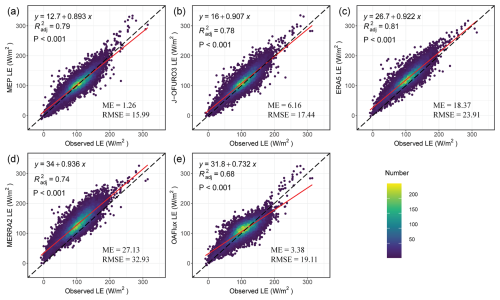

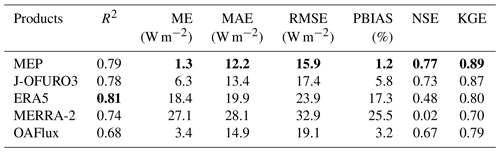

4.4.2 Validation of global latent heat products against the observational sites

To evaluate the discrepancies between MEP-estimated LE and other datasets, this study validated global-scale LE at 129 observational sites (as depicted in Fig. 8 and Table 6). MEP-estimated LE showed strong consistency with buoy observations, achieving an R2 of 0.79, an ME of 1.26 W m−2, and an RMSE of 16 W m−2, all surpassing those of alternative products, underscoring its superior performance. Moreover, the MEP method exhibited superior performance with a higher NSE value of 0.77 and KGE of 0.89, demonstrating enhanced accuracy, reliability, and robustness. According to the RMSE evaluation criterion, the ranking of best-performing LE products was MEP, J-OFURO3, OAFlux, ERA5, and MERRA-2. In a recent comprehensive assessment of 15 global ocean LE products (Tang et al., 2023), RMSE values ranged from 17.2 to 45.3 W m−2, in which J-OFURO3 emerged as the best-performing product with the lowest RMSE of 17.2 W m−2, highest correlation coefficient (R) of 0.89, and ME of 6.5 W m−2. Studies have also shown minimal bias was given by J-OFURO3 on a daily scale (Bentamy et al., 2017). This superior performance of the J-OFURO3 dataset can be attributed to the use of continuously updated bulk algorithms (COARE 3.0 version), the ongoing optimization of near-surface parameters (Tomita et al., 2018), and the improved spatial resolution (0.25°). In this study, the improved MEP estimation of LE outperformed that of J-OFURO3, demonstrating higher accuracy and lower error (), thereby establishing it as the most accurate global LE product currently available.

Figure 8Scatter density plots of latent heat flux taken from different products versus observations from 129 buoy stations during the period 1988–2017: (a) improved MEP model, (b) J-OFURO3, (c) ERA5, (d) MERRA-2, and (e) OAFlux. A total of 15 444 records of latent heat observations are included.

Table 6Evaluation of latent heat flux from different methods against buoy observations.

Note that the evaluation period spans from 1988–2017, and the best-performing statistics are indicated in bold type.

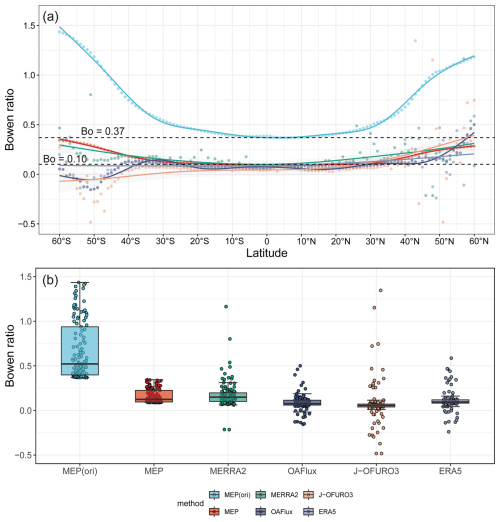

Figure 9Global ocean latitudinal averaged Bowen ratio derived by the MEP method and four other products from 1988–2017. (a) Latitudinal averaged Bowen ratio derived from the MEP model using original and modified Bowen ratio formulas, with points fitted by a generalized additive model (GAM). (b) Statistical distribution of the latitudinal annual mean Bowen ratio.

4.4.3 Comparisons of Bowen ratios

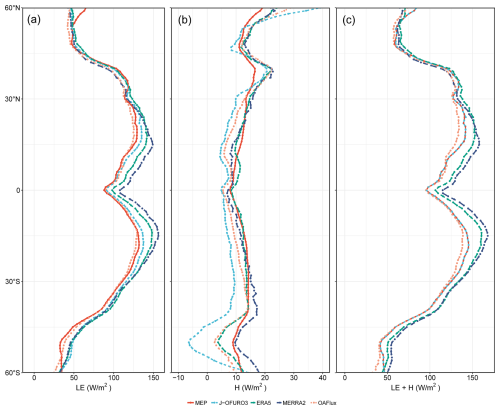

The improved MEP model achieved accurate LE estimation after refining the process of partitioning the surface energy budget, specifically through revisions to the Bowen ratio. The improved MEP method notably decreased the global-scale Bowen ratio, as illustrated in Figs. 9 and 10. Regarding latitude averages, the Bowen ratio of the original MEP formula ranged from 0.37 to 1.48 (with a median of 0.80), whereas the modified MEP Bowen ratio ranged from 0.09 to 0.35 (median of 0.18). Specifically, in the low-latitude region (10° S–10° N), the Bowen ratio of the modified MEP formula decreased from 0.37 to approximately 0.1, aligning closely with the Bowen ratios obtained from other reanalysis products (MERRA-2, ERA5, OAFlux, and J-OFURO3). Globally, the median Bowen ratios of the products were as follows: MERRA-2 (0.15), MEP (0.12), ERA5 (0.09), OAFlux (0.08), and J-OFURO3 (0.06). Spatially, the MEP Bowen ratio resembled ERA5 in middle to low latitudes but exhibited deviations from other products at high latitudes, where those products showed fluctuating changes in the Bowen ratio (Fig. 10). For instance, other products displayed abrupt transitions from negative to positive Bowen ratios in the Arctic and Antarctic regions, whereas MEP-derived values demonstrated greater stability in variations at higher latitudes. This discrepancy was likely due to the reanalysis products relying on the bulk method, which was sensitive to variations in wind speed and temperature gradients, leading to errors in simulating high wind speeds at the poles and causing fluctuations in latent and sensible heat. In contrast, the MEP model strictly adheres to energy conservation principles and operates independently of wind speed and temperature gradients, resulting in a more accurate estimate of the Bowen ratio. For example (Fig. S9), at the high-latitude Papa buoy site (144.9° W, 50.1° N), the Bowen ratio estimated by MEP (median 0.24) closely matched the observed Bowen ratio (median 0.23). In contrast, all other products underestimated the Bowen ratio, with J-OFURO3 (median −0.09) and OAFlux frequently exhibiting negative values. The Bowen ratio derived from MEP fit well with a generalized additive model (GAM) (Fig. 9). The implicit functional relationship between Bowen ratio and latitude is expressed as follows (R2=0.996, p<0.001): , where f(lat) represents a smoothing function derived from a smooth curve, and ε denotes the error term. However, the specific functional form of f(lat) cannot be explicitly determined. Therefore, a polynomial regression method was employed to explicitly fit Boa and latitude, resulting in the following (R2=0.91, p<0.001): (as in Fig. S10). This equation can serve as a reference for partitioning surface energy in data-sparse oceanic regions.

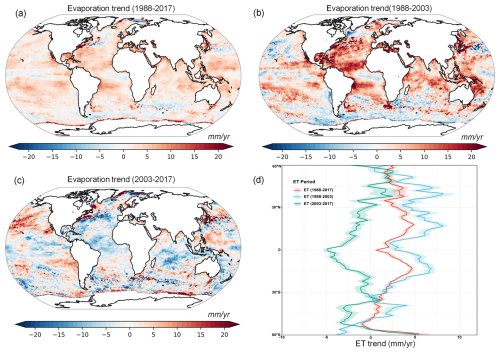

4.5 Spatial–temporal variability of ocean evaporation

Heat flux reflects the energy exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere, while evaporation (ET) reflects moisture exchange within the water cycle. The spatiotemporal patterns in evaporation were analyzed using Sen's slope and Mann–Kendall test methods (Fig. 11). For the global ocean, approximately 74 % of the regions showed an increasing trend, with about 27 % of the grids exhibiting statistically significant increases (p<0.05). In contrast, 26 % displayed a decreasing trend, with only 5 % of the grids showing a statistically significant decrease (p<0.05). For whole periods, the regions with the highest increasing trends were predominantly observed near western boundary current systems, the convergence zones of the East Australian Current and the South Equatorial Current, and the convergence zones of the Eastern South Equatorial Current and the Brazil Current along South America. Decreasing trends were primarily observed in equatorial regions of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, as well as near the Labrador and Kuroshio currents and north of the Antarctic Circle. It was indicated that regions with significant increases (decreases) in evaporation generally correspond closely to the distribution of major warm currents (cold currents) spatially. However, global ocean evaporation experienced a notable shift around 2003, as illustrated in Fig. 11b and c. The downward trend observed from 2003–2017 counteracted a significant portion of the growth trend that occurred during the previous 16 years (1988–2003), particularly evident in the midlatitude regions (15° S–20° N). In the middle to low latitudes (0–30° N), nearly all ocean grids exhibited opposite trends around 2003. Spatially, regions that displayed the largest increasing trends during 1988–2003 transitioned to show the most substantial decreasing trends between 2003 and 2017. This includes regions associated with western boundary current systems, convergence zones of the East Australian Current and the South Equatorial Current, and equatorial regions of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans (Fig. 11c). To further investigate the shift in ocean evaporation after 2003, we analyzed the interannual variability of global annual mean area-weighted evaporation using all available datasets (as shown in Fig. 12).

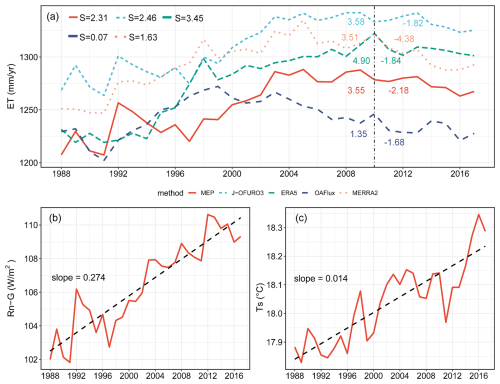

Figure 12Time series of area-averaged multi-annual mean evaporation from the improved MEP method (a), available energy (b), and sea surface temperature (c) over the global oceans during 1988–2017. The dotted black line in panel (a) marks the year 2010, and the label “S = 2.31” indicates that the MEP-estimated global multi-annual mean evaporation increased at a rate of 2.31 mm yr−1 during 1988–2017, with change rates of different ET datasets represented by various colors. The dashed black lines in panels (b) and (c) denote the linear regression lines.

Over the multi-year period from 1988 and 2017, MEP, J-OFURO3, ERA5, and MERRA-2 all exhibited significant increasing trends in ET. MEP estimated an evaporation increase rate of 2.31 mm yr−1, whereas OAFlux showed a non-significant trend (Fig. 12). While different datasets revealed varying magnitudes of evaporation changes, most exhibited a similar temporal pattern: an increasing trend from 1988 to around 2003, followed by a hiatus during 2003–2010, and ultimately a decreasing trend after 2010 (Fig. 12a). Specifically, MEP indicated an increasing trend in evaporation of 3.58 mm yr−1 from 1988–2010, followed by a decrease of 2.18 mm yr−1 after 2010 (Fig. 12a). The slowdown and transition of evaporation during 2003–2010 aligned with the concept of a “global warming hiatus” (Medhaug et al., 2017; Sung et al., 2023), referring to the period when global mean surface air temperatures did not continue to rise between 1988 and 2012. Previous studies have proposed four potential explanations for this global warming hiatus: internal variability, external drivers, the Earth's response to CO2, and radiative forcing (Medhaug et al., 2017). This study indicates that changes in radiative forcing (Fig. 12b) can significantly affect the interannual variability of evaporation (Fig. 12a) and surface temperature (Fig. 12c). This finding is consistent with previous research that attributed more than 50 % of the uncertainty in MEP-modeled fluxes to the radiation term (Huang et al., 2017). Although surface temperature began to increase after 2012, the decrease in available energy remained the primary driver behind the decline in evaporation.

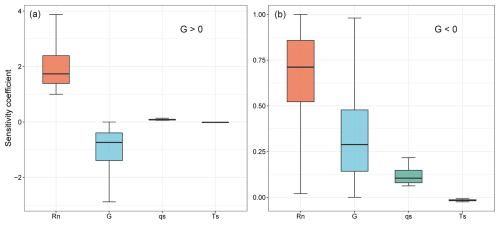

5.1 Quantifying the impact of heat storage and radiation with sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis revealed the significant influence of input variables on latent heat flux derived from the MEP model. Notably, the heat storage (G) exhibited seasonal variations with both positive and negative values (Fig. 13). Positive G values coincided predominantly with summer in the Northern Hemisphere (winter in the Southern Hemisphere), specifically from June to August (Figs. 4 and S5). During this season, intensified solar radiation enhances the net energy input (Rn) at the ocean surface, leading to heat absorption and retention. Consequently, the energy available (Rn−G) for evaporation diminishes. The analysis indicated that Rn significantly influenced the energy-driven evaporation process, with a sensitivity coefficient exceeding 1 (median 1.74), highlighting its pivotal role. In contrast, G negatively impacted evaporation, as indicated by a sensitivity coefficient of Specific humidity (median 0.08) and sea surface temperature had relatively minor effects, consistent with previous MEP model findings focused on terrestrial surfaces (Isabelle et al., 2021).

Figure 13Sensitivity coefficient associated with input variables for the improved MEP method at all 129 buoy stations: (a) for positive G values and (b) for negative G values.

Conversely, negative values of heat storage predominate during winter, particularly from December to February in the Northern Hemisphere (June to August in the Southern Hemisphere). Despite reduced solar radiation during this period, residual heat stored from summer gradually releases into the atmosphere, resulting in greater energy output than input. This surplus energy increases the available energy for evaporation, leading to a positive sensitivity coefficient for G (median 0.29), second only to Rn (median 0.71). Consequently, this process generally reduces sea surface temperature, resulting in a negative sensitivity coefficient for surface temperature. Overall, these findings underscored the significant influence of Rn on latent heat flux, with G ranking as the second most influential variable in MEP estimates over ocean surfaces. For instance, a 10 % decrease in positive G yielded a 7.4 % increase in evaporation, while a 10 % increase in negative G resulted in a 2.9 % increase in evaporation, assuming other variables remain constant. Thus, Rn and G emerged as two primary drivers of oceanic evaporation, with humidity and temperature exerting minimal influence.

The accuracy of available energy estimates has a significant impact on LE modeling, as it serves as the direct energy source for partitioning latent and sensible heat fluxes. Although the bulk methods (e.g., COARE 3.0 algorithms) used for estimating heat fluxes are independent of surface energy budget allocation, discrepancies in LE estimation still correlate strongly with validated biases against observations in available energy estimates (see Tables 3 and 4). Notably, the MERRA-2 product exhibited higher errors in simulating Rn and G compared to observations, leading to significant biases in LE estimation. In contrast, the ERA5 product demonstrated superior performance in simulating Rn and G, thereby achieving higher accuracy in LE estimation. Consequently, the energy-balance-based MEP model excels in accurately estimating surface heat fluxes by directly reflecting energy allocation. Unlike bulk methods, the MEP approach reduces sensitivity to temperature and humidity gradients, thereby minimizing uncertainties in LE simulations (Pelletier et al., 2018). This advancement enhances the MEP model's utility in global energy and water cycle research, particularly pertinent for future climate change studies.

5.2 Discrepancy in empirical Bowen ratio formulas

Bo plays a crucial role in understanding the surface energy partitioning process. In this study, four empirical formulas were utilized to modify the MEP model and evaluated against the observed LE, each with distinct conditions of applicability and suitability for integration with the MEP model:

-

was derived from direct observational data fitting (Hicks and Hess, 1977). This formula was applicable for surface temperatures above 16 °C, particularly within latitudes between 40° N and 40° S, making it more suitable for lower-latitude regions.

-

was derived using the Priestley–Taylor model under advection-free conditions (Priestley and Taylor, 1972). The coefficients were determined based on a mean α value of 1.26, although this value can vary in practice. Recent studies have revealed significant discrepancies due to the neglect of the interaction between variations in Rn and Ts (Yang and Roderick, 2019).

-

To address this limitation, the equation was developed based on the maximum evaporation theory, considering the feedback mechanisms between Rn and Ts while assuming that G is small or negligible. The empirical coefficient 0.24 was determined by fitting B and Ts across the global ocean surface (Yang and Roderick, 2019).

-

was formulated based on principles derived from atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) theory (Liu and Yang, 2021), with coefficients also fitted from relationships between Boa and Ts.

It should be noted that the derivations of and were based on fitting using LE from the OAFlux dataset rather than direct buoy observations. Overall, the MEP model incorporated with exhibited superior accuracy at both localized and global scales, effectively mitigating the underestimation of LE in its original estimates.

5.3 Contributions and implications of this study

The main contributions of this study include the following:

-

The MEP model's energy balance equation over water surfaces was revised to explicitly consider heat storage effect. This correction highlights the importance of heat storage in estimating LE.

-

The energy partitioning of the MEP model was revised to incorporate empirical Bowen ratio formulas, significantly improving the heat flux estimations.

-

This study conducted the first thorough global assessment of heat storage using extensive buoy observations and remotely sensed data, enabling the MEP model to produce the most accurate global LE estimates.

This study addresses the issue of underestimating LE by the original MEP model, increasing the global average LE from 53 to 93 W m−2 while reducing sensible heat flux from 25 to 12 W m−2, improving the partitioning of energy budget. The improved MEP model provided precise LE estimates compared to existing datasets like J-OFURO3, ERA5, MERRA-2, and OAFlux, enabling it to become a valuable benchmark dataset for global evaporation studies.

From a methodological perspective, the improved MEP method emerged as a novel approach for estimating energy fluxes that diverges from traditional bulk methods. The conventional bulk method requires multiple input parameters, including air temperature, specific humidity, wind speed, sea surface temperature, atmospheric pressure, and the observational height of all parameters (Fairall et al., 2003; Tomita et al., 2021). This method demands numerous input variables, and the estimated fluxes are highly sensitive to changes in temperature and humidity gradients. In contrast, the improved MEP model requires only net radiation, heat storage, surface temperature, and atmospheric pressure to simultaneously obtain latent and sensible heat fluxes, making it more flexible to operate and robust against variations in input variables. Furthermore, the improved MEP model is not constrained by the magnitude of heat storage and theoretically can be applied across various temporal scales (including subdaily and daily), beyond the monthly scale used in this study. This underscores the applicability of the MEP method in addressing the constraints of traditional bulk methods, providing another independent approach to estimating heat fluxes across diverse environmental conditions.

This study applied the improved MEP model to ocean surface, with potential for future extension to lake and reservoir surfaces. Compared to the Penman model for water body evaporation (Tian et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2022; Bai and Guo, 2023), the major advantage of the MEP method lies in its independence from wind speed, provided that heat storage can be determined using an equilibrium temperature-based approach (McMahon et al., 2013; Zhao and Gao, 2019). The global LE dataset generated in this study, due to MEP's insensitivity to variations in air temperature and humidity, can be applied in research related to ocean salinity (Liu et al., 2019), ocean warming (Cheng et al., 2022), and global climate change and water cycle studies (Konapala et al., 2020).

5.4 Limitations

The improved MEP method proposed in this study offers a novel approach for estimating ocean heat fluxes, producing a validated long-term global dataset with high accuracy and spatiotemporal continuity. Despite its advancements, the proposed MEP method has several limitations that require further refinement:

-

Uncertainty of driving data. The input variables of net radiation, heat storage, and sea surface temperature for the MEP model were sourced from the state-of-the-art satellite-based J-OFURO3 dataset. This dataset was constructed using observations from multiple satellite sensors. The net radiation in J-OFURO3 was derived by combining data from the CERES and the International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project (ISCCP) via the creeping sea-fill method, along with 12 global sea surface temperature products (Tomita et al., 2019). Consequently, the uncertainty of the MEP-estimated fluxes may arise from biases in input data derived from various satellite sensors and their associated analysis methods. Therefore, it is essential to integrate multiple approaches to assess the uncertainty associated with the input datasets. Moreover, due to the limited temporal duration of the J-OFURO3 dataset, future work should utilize input datasets with longer time series, finer spatiotemporal resolution (Liang et al., 2022), and higher accuracy to advance ocean heat flux estimations using the MEP method.

-

Heat storage determination. This study did not employ a direct calculation method to obtain heat storage. Given the unclear relationship between heat storage and changes in ocean heat content at varying depths (as shown in Table 4), we utilized an energy balance residual-based approach to indirectly estimate heat storage. Consequently, this may render the MEP method susceptible to uncertainties in heat storage data derived from auxiliary flux datasets. Future research should focus on understanding the relationship between ocean heat content changes in the upper 100 m and heat storage, with the goal of establishing a functional relationship between water column temperature at different depths and heat storage.

-

Bowen ratio improvement. Accurate determination of the Bowen ratio in high-latitude regions remains challenging. The Bowen ratio derived from the MEP method showed significant discrepancies with other datasets in these areas (Fig. 10), particularly in sea-ice-covered Arctic regions, where other datasets exhibited notable overestimations and irregular fluctuations. Therefore, incorporating more observational data from high-latitude regions is essential for a better understanding of energy partitioning patterns.

The GOHF-MEP dataset produced with the MEP method, which includes global latent heat flux and sensible heat flux at a monthly scale from 1988–2017, can be freely downloaded from the Figshare platform (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26861767.v2, Yang et al., 2024). All the datasets used in this study are publicly available online and are described in the “Data materials” section.

In this study, we developed a new global ocean heat flux product (GOHF-MEP) covering the period from 1988–2017. This product is grounded in a maximum entropy production theory framework, incorporating heat storage impacts and Bowen ratio adjustments. GOHF-MEP represents the first energy-balance-based dataset that diverges from existing global ocean heat flux datasets derived from bulk methods. To assess the accuracy of the input variables for the maximum entropy production framework, we utilized five global datasets, including two remote-sensing-based and three reanalysis-based, along with four global datasets of heat storage derived from the energy balance equation and ocean heat content changes. We employed data fusion methods, including arithmetic averaging and the Bayesian three-cornered hat method, to identify optimal input datasets through validation against observations. The performance of the newly produced GOHF-MEP dataset was evaluated against extensive observations from 129 globally distributed buoy stations using multiple statistical metrics. It was also compared with four auxiliary products: J-OFURO3, ERA5, MERRA-2, and OAFlux. Moreover, we analyzed the long-term spatial–temporal variability of ocean latent heat flux. Ultimately, we investigated the impacts of ocean heat storage, net radiation, and Bowen ratio changes on heat flux estimations and surface energy partitioning.

The MEP framework provides new estimates of global heat fluxes. The MEP-estimated long-term annual mean latent heat flux is 93 W m−2 (equivalent to 1196 mm yr−1 of evaporation) during the period from 1988–2017. This estimate is intermediate compared to other global flux products, which range from 90 W m−2 (OAFlux) to 101 W m−2 (MERRA-2). The MEP-estimated sensible heat flux is 12 W m−2, falling within the range of 10.17 W m2 (J-OFURO3) to 13 W m2 (MERRA-2) reported by other current products. Compared with previous heat flux products, the MEP-estimated latent heat demonstrated higher accuracy when validated against observations, with an ME of 1.26 W m−2, an RMSE of 16 W m−2, and a KGE value of 0.89, outperforming all other contemporary global products. Approximately 74 % of oceanic regions experienced an increasing trend in evaporation from 1988–2017. In terms of long-term temporal variability, the global annual mean evaporation exhibited an increase rate of 3.58 mm yr−1 from 1988–2010 but subsequently declined at a rate of 2.18 mm yr−1 from 2010–2017, which was consistent with changes in surface available energy.

This study demonstrates that the improved MEP framework has significantly improved the accuracy of the original MEP theory, addressing both the underestimation of latent heat and the overestimation of sensible heat flux. This improvement was achieved by incorporating the impact of heat storage and modifying the Bowen ratio formula within the MEP theory. The consideration of heat storage resolved the issue of seasonal phase mismatches (approximately 6-month lags) between MEP estimates and buoy observations. Building upon this improvement, this study further optimized the energy partitioning process by correcting the Bowen ratio, linearly adjusting the equilibrium Bowen ratio to align with actual conditions. Four empirical Bowen ratio formulas for modifying the MEP method were assessed globally, identifying as the most accurate formula for estimating latent heat flux within MEP method. The impact of heat storage on estimating heat fluxes was quantified through sensitivity analysis. Net radiation and heat storage were identified as the primary drivers of evaporation estimates. A 10 % decrease in positive heat storage led to a 7.4 % increase in evaporation, whereas a 10 % increase in negative heat storage resulted in a 2.9 % increase.

Compared to existing bulk methods, the MEP model offers several advantages, including the requirement for fewer input variables, independence from wind speed, and insensitivity to variations in temperature and humidity. The MEP-derived ocean heat flux dataset has been validated and provides accurate estimates of latent heat flux. Additionally, this MEP method can be applied to estimate evaporation from other deep-water surfaces, such as lakes and reservoirs where heat storage is significant. Overall, the MEP-derived ocean heat flux dataset provides high global accuracy, fine spatial resolution (0.25°), and extensive long-term temporal records. This dataset is expected to be valuable for applications related to global ocean warming, hydrological cycles, and their interactions with other Earth system components in the context of climate change.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-1191-2025-supplement.

YY and HS developed the methodology and designed the experiments. WZ contributed the conceptual design. YY and WZ collected and processed the data. YY wrote the first draft of the paper under the supervision of the other authors. All authors participated in revising and editing the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We acknowledge the GTMBA Project Office of NOAA/PMEL for providing the Global Tropical Moored Buoy Array observations. This study was primarily funded by the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program (grant no. 2022xjkk0105) (Huaiwei Sun). The authors acknowledge funding from the NSFC project (grant nos. 52079055, 52011530128, 202100-3211, 52039004). Huaiwei Sun and Wenxin Zhang acknowledge funding from the NSFC–STINT projects (grant nos. 202100-3211 and CH2019-8281). Wenxin Zhang was supported by grants from Swedish Research Council VR (no. 2020-05338) and Swedish National space Agency (grant no. 209/19).

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 52079055, 52011530128, 202100-3211, 52039004), the Swedish Research Council VR (2020-05338), the STINT Joint China–Sweden mobility grant (CH2019-8281), and the Swedish National Space Agency (grant no. 209/19).

This paper was edited by Bo Zheng and reviewed by Xiaofeng Liu and one anonymous referee.

Andreas, E. L. and Cash, B. A.: A new formulation for the Bowen ratio over saturated surfaces, J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim., 35, 1279–1289, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1996)035{%}3C1279:ANFFTB{%}3E2.0.CO;2, 1996.

Andreas, E. L., Persson, P. O. G., and Hare, J. E.: A bulk turbulent air–sea flux algorithm for high-wind, spray conditions, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 38, 1581–1596, https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JPO3813.1, 2008.

Andreas, E. L., Jordan, R. E., Mahrt, L., and Vickers, D.: Estimating the Bowen ratio over the open and ice-covered ocean, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 118, 4334–4345, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20295, 2013.

Bai, P. and Guo, X.: Development of a 60 year high-resolution water body evaporation dataset in China, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 334, 109428, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109428, 2023.

Bai, P. and Wang, Y.: The importance of heat storage for estimating lake evaporation on different time scales: Insights from a large shallow subtropical lake, Water Resour. Res., 59, e2023WR035123, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023WR035123, 2023.

Bentamy, A., Piolle, J. F., Grouazel, A., Danielson, R., Gulev, S., Paul, F., Azelmat, H., Mathieu, P. P., von Schuckmann, K., Sathyendranath, S., Evers-King, H., Esau, I., Johannessen, J. A., Clayson, C. A., Pinker, R. T., Grodsky, S. A., Bourassa, M., Smith, S. R., Haines, K., Valdivieso, M., Merchant, C. J., Chapron, B., Anderson, A., Hollmann, R., and Josey, S. A.: Review and assessment of latent and sensible heat flux accuracy over the global oceans, Remote Sens. Environ., 201, 196–218, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.08.016, 2017.

Beven, K.: A sensitivity analysis of the Penman–Monteith actual evapotranspiration estimates, J. Hydrol., 44, 169–190, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(79)90130-6, 1979.

Bourras, D.: Comparison of five satellite-derived latent heat flux products to moored buoy data, J. Climate, 19, 6291–6313, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3977.1, 2006.