the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

A global dataset of soil organic carbon mineralization in response to incubation temperature changes

Shuai Zhang

Mingming Wang

Jinyang Zheng

Microbial decomposition of soil organic carbon (SOC) is a major source of atmospheric CO2 and a key component of climate–carbon feedbacks. Understanding how SOC mineralization responds to temperature is essential for improving climate projections. Here, we compiled a global dataset of laboratory incubation experiments measuring SOC mineralization across diverse soils and temperature regimes. The dataset reveals that 84 % of samples originated from surface soils (0–30 cm), and 50 % of incubations lasted fewer than 50 d. Incubation temperatures ranged from −10 to 60 °C, with temperature intervals used to estimate temperature sensitivity (Q10) spanning 2–40 °C; notably, 81 % of Q10 estimates were based on intervals exceeding 5 °C. Moreover, in 61 % of cases, the lower incubation temperature for Q10 estimation differed from the mean annual temperature at the sampling site by more than 5 °C, indicating a mismatch with in situ conditions. Our analysis highlights critical gaps in current experimental designs, particularly the underrepresentation of subsoils (>30 cm) and the use of temperature ranges that deviate from field conditions. We further evaluated the ability of 16 temperature response functions used in 69 land surface and/or carbon models to capture SOC mineralization patterns. Most models failed to reproduce empirical temperature response, especially at higher temperatures, albeit multi-term exponential functions showed relatively better performance. By coupling our dataset with a two-pool carbon model, we found that external environmental constraints and the intrinsic temperature response (including SOC decomposability and microbial processes) similarly influence the temperature sensitivity of SOC mineralization at the global scale, with their relative importance varying across ecosystem types. Our findings underscore the need for incubation experiments that better represent field conditions – both in depth and temperature range – and call for improved model parameterizations to enhance SOC feedback projections under future climate scenarios. The dataset is archived and publicly available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25808698 (Zhang et al., 2025).

- Article

(4217 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(877 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Soils annually release approximately five times more CO2−C to the atmosphere via microbial mineralization of soil organic carbon (SOC) than all anthropogenic fossil fuel emissions combined (Tang et al., 2020). As a key flux in the global carbon cycle, this soil-derived CO2 efflux is projected to intensify under global warming (Lei et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022) due to the inherent temperature sensitivity of microbial decomposition (Davidson and Janssens, 2006). Yet, the magnitude and mechanisms of this feedback remain contentious (Crowther et al., 2016; Soong et al., 2021), posing a critical uncertainty in Earth System Models (ESMs) projections of future climate–carbon dynamics.

The temperature sensitivity of SOC mineralization is commonly expressed as Q10 – the factor by which the mineralization rate increases for every 10 °C rise in temperature. Q10 is typically calculated following Eq. (1):

where and are the SOC mineralization (often microbial respiration) rates at low temperature (T1) and high (T2) temperatures, respectively. Most ESMs adopt a constant or temperature-dependent Q10 value (Luo et al., 2016, 2020), but empirical Q10 estimates vary widely due to numerous influencing factors (Haaf et al., 2021; Patel et al., 2022), including calculation approaches (Hamdi et al., 2013), environmental constraints such as soil pH (Craine et al., 2010) and clay content (Hartley et al., 2021), climatic conditions like precipitation (Li et al., 2020), and microbial community traits (Wang et al., 2021). These controls can be grouped into three primary mechanisms: (1) Carbon pool quality: the chemical composition of SOC influences its thermodynamic properties and decomposability (Haddix et al., 2011); (2) Microbial community structure and function: Variations in microbial traits affect SOC decomposition efficiency and enzyme production (Karhu et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2023); and (3) Physicochemical protection and accessibility: Soil texture, aggregation, and mineral interactions modulate the accessibility of SOC to microbial enzymes (Gershenson et al., 2009). While these mechanisms are often discussed independently, their relative contributions and interactions remain poorly understood at the global scale (Jones et al., 2003).

Temperature sensitivity is typically assessed via either field or laboratory incubation experiments. Field studies reflect in situ conditions but are confounded by numerous environmental variables (e.g., plant inputs, soil moisture variability), and it is difficult to separate root and microbial respiration. Moreover, field measurements are challenging to conduct continuously, especially in remote ecosystems. Laboratory incubations, while simplified and often subject to preparation artifacts (e.g., sieving, drying, rewetting), offer controlled conditions that isolate specific mechanisms and allow for systematic comparisons across soils and temperatures (Zhang et al., 2020). Importantly, although many laboratory studies have yielded mechanistic insights, they are often limited in spatial scope or designed to test specific hypotheses. Yet, taken together, the body of global incubation data represents an underutilized resource for addressing broad-scale questions about SOC temperature sensitivity.

Here, we compile and synthesize a global dataset of time-series measurements of SOC mineralization under controlled laboratory incubation conditions, encompassing diverse soil types, climatic zones, and incubation protocols. The dataset is valuable for characterizing SOC mineralization processes and their response to temperature in relation to various soil properties and incubation conditions. To showcase the dataset's utility and scientific potential, we used it in a soil carbon model as a case study. This analysis demonstrates its applicability to process-based modeling and its contribution to understanding soil carbon dynamics. Specially, we evaluate the performance of temperature response functions currently used in land surface and/or carbon models (hereafter referred to as carbon models) against observed Q10 values estimated using Eq. (1), and use a two-pool carbon model to simulate SOC mineralization and assess the relative influence of different regulatory mechanisms on temperature sensitivity. By integrating empirical observations with process-based modeling, our study provides mechanistic insights into the drivers of SOC temperature sensitivity and informs efforts to improve Earth system model projections under climate change.

We compiled a global dataset of laboratory incubation experiments to investigate the temperature sensitivity of SOC mineralization. Literature searches were conducted using the Web of Science and the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). The search terms included:

soil AND (respir* OR ((carbon OR CO2 OR carbon dioxide OR organic matter) AND (flux OR efflux OR emission OR release OR loss OR mineraliz* OR decompos*))) AND (temperature OR warm* OR cool*) AND incubat*

In addition to dataset queries, we screened all studies cited in five previous synthesis papers on temperature sensitivity of SOC mineralization (Fierer et al., 2006; Hamdi et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2020; Schädel et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). To be included in our dataset, studies had to meet the following criteria:

-

The incubated soil must be sampled from the mineral layer;

-

Each experiment must incubate the same soil at two or more temperatures;

-

All other incubation conditions (e.g., moisture) must be identical across temperature treatments and maintained throughout the incubation; and

-

Time-series data of carbon mineralization rates or cumulative carbon mineralization must be reported.

Using these criteria, we identified 191 publications, encompassing 721 distinct soils and totaling 21979 data points on SOC mineralization (Fig. 1).

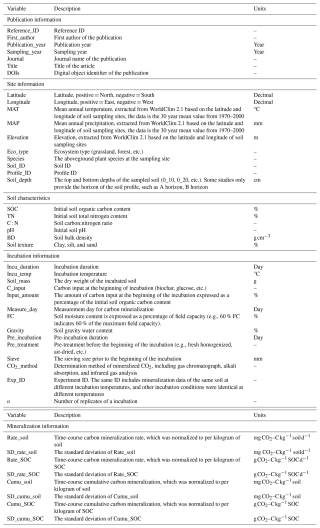

Figure 1Geographic distribution of soil samples. (A) soil sample locations; (B) distribution across climate conditions and ecosystems. Numbers in parentheses show the sample size in the specified ecosystem.

When available, numerical data were directly extracted from the publications, and graphical data were digitized using the WebPlotDigitizer (Burda et al., 2017). SOC mineralization rates were standardized to and . Cumulative mineralization was also recorded as g CO2–C kg−1 SOC and g CO2–C kg−1 soil, corresponding to the total mineralized carbon over the duration of the incubation. We also compiled ancillary information when available, including soil properties (e.g., pH, total nitrogen (TN), carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C : N), soil bulk density (BD), and texture), site characteristics (geographic coordinates and ecosystem type), and experimental design (incubation temperature, duration, moisture condition, and pretreatment) (Table 1). Based on the recorded geographic coordinates of sampling locations, we extracted 19 climate variables from WorldClim V2.0 at a spatial resolution of 1 km2 (Fick and Hijmans, 2017). All complied data are deposited to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25808698 (Zhang et al., 2025) and are publicly accessible.

3.1 Spatial coverage

Our dataset captures a broad global distribution of soil incubation experiments, with sampling sites concentrated in China, Europe, and the United States (Fig. 1A). However, samples are relatively sparse in Australia, Canada, and Russia, with almost absent in Africa. This geographic imbalance is particularly concerning given the importance of tropical and high-latitude cold regions for global carbon storage and their heightened vulnerability to climate change. Addressing these data gaps is critical for improving the accuracy of global SOC-climate feedback projections.

The dataset covers major terrestrial ecosystems (Fig. 1B), including croplands (226 sites), forests (199), and grasslands (184), but includes relatively few samples from tundra (43), wetlands (53), and deserts (16). Yet, tundra and wetland soils are known for their high SOC content and may exhibit distinct temperature responses due to unique environmental conditions (Wang et al., 2022). In tundra ecosystems, SOC is dominated by particulate organic carbon, which is more sensitive to warming than mineral-associated organic carbon (Georgiou et al., 2024). Moreover, freeze-thaw cycles can disrupt microbial and physical protection mechanisms, altering SOC turnover (Schuur et al., 2009). Similarly, wetland soils experience fluctuating redox conditions driven by water table changes, potentially leading to nonlinear SOC responses to warming (Wang et al., 2017). These complexities reinforce the need for targeted studies in underrepresented ecosystems.

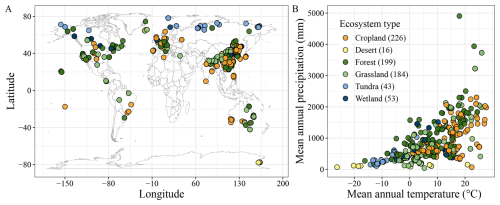

Figure 2Basic characteristics of the incubation dataset. The distribution (frequency or density) of soil organic carbon content (A), incubation temperature (B), soil sampling depth (C), incubation duration (D), temperature range (T1 and T2 in Eq. 1) used for Q10 estimation (E), absolute temperature range () (F), temperature difference between the low incubation temperature (T1 in Eq. 1) and the local mean annual temperature (MAT) at the sampling site (G), absolute temperature difference () (H). In panels (E) and (G), the blue circles represent the low incubation temperature (T1 in Eq. 1), the red circles indicate the high incubation temperature (T2 in Eq. 1), and the yellow circles correspond to the mean annual temperature at the sampling site. Note the log 10 scale of the y axis in panels (E) and (G). Most of the data points in panel (E) fall within the temperature ranges of 15–25, 5–15, 5–25, 15–35, and 25–35 °C.

SOC content in the dataset ranges from 0.04 %–58.85 %, with a median of 2.48 % (Fig. 2A). Notably, 73 % of samples contain less than 5 % SOC, with higher values mostly occurring in wetland soils. Incubation temperatures range from −10 to 60 °C, with a median of 17 °C and frequent use of standard temperatures such as 5, 15, and 25 °C (Fig. 2B). Q10 values, calculated from paired temperature treatments, are most derived from 15–25 °C (Fig. 2E), with 10 °C temperature difference (i.e., ΔT, the difference between T2 and T1 in Eq. 1) accounting for 34 % of cases (Fig. 2F). However, only 19 % of experiments used ΔT≤5 °C, a range more reflective of projected climate warming (IPCC, 2023).

3.2 Incubation temperature

While laboratory incubations allow precise control of environmental variables, their ecological relevance depends critically on the selection of incubation temperatures. SOC mineralization often responds nonlinearly to warming (Melillo et al., 2017), especially in cold ecosystems where small temperature increases can trigger large CO2 emissions (Turetsky et al., 2020). However, many studies apply large ΔT values (>10 °C), which may obscure subtle thresholds, suppress key microbial feedbacks, and limit the transferability of findings to field conditions.

This limitation is compounded by the mismatch between incubation temperature and field conditions. We compared the low incubation temperature (i.e., T1 in Eq. 1) used for estimation to the local mean annual temperature (MAT) at each sampling sites (Fig. 2G). In 61 % of the cases, the absolute difference between T1 and MAT exceeded 5 °C (Fig. 2H), potentially biasing Q10 estimates, as temperature sensitivity is itself temperature-dependent (Alster et al., 2023; Hamdi et al., 2013; Patel et al., 2022). To enhance ecological validity, we recommend future studies align incubation temperatures more closely with local MATs, particularly when estimating Q10.

Most soil samples were collected from surface layers: 84 % originate from the 0–30 cm depth (Fig. 2C). However, subsoils (>30 cm) store more than twice the SOC of topsoil globally (Jobbágy and Jackson, 2000), and emerging evidence suggests they are not inert, but can respond sensitively to warming (Hicks Pries et al., 2017, 2023). SOC dynamics in deeper layers are governed by different stabilization processes and environmental controls, including lower oxygen availability, reduced root inputs, and greater mineral association (Jia et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2021). These vertical gradients shape SOC quality, microbial access, and thus, temperature sensitivity. Current underrepresentation of deep soils in incubation experiments limits our ability to predict long-term carbon–climate feedbacks and highlights the need for deeper sampling in future work.

3.3 Incubation duration

Incubation durations vary widely across studies. While some experiments extend for several years, 80 % of the incubations lasted <113 d, and half were <54 d (Fig. 2D). Short-term incubations are efficient and cost-effective, and are well suited for capturing the dynamics of labile carbon pools that dominate initial CO2 release (Schädel et al., 2020). They also minimize microbial adaptation and maintain more natural soil structure. However, they may overlook the slower dynamics of recalcitrant carbon pools, which contribute substantially to long-term SOC persistence and climate feedbacks (Schmidt et al., 2011).

In contrast, long-term incubations are essential for capturing the decomposition of slow-cycling SOC fractions, especially in the absence of new carbon inputs. As labile carbon is depleted, persistent carbon pools increasingly dominate respiration, providing insights into intrinsic SOC stability (Schädel et al., 2020). Long-term studies also enable assessment of microbial community shifts and potential feedbacks under sustained warming (Guan et al., 2022; Melillo et al., 2017). Yet, they also introduce new complexities, including potential changes in soil structure, microbial acclimation, and moisture loss, which may confound temperature effects (Kirschbaum, 2006). We advocate for a combined approach that integrates both short- and long-term incubations. This dual strategy can capture early-stage microbial dynamics, as well as long-term decomposition pathways of stable carbon pools. By leveraging both timescales, researchers can better disentangle microbial versus physiochemical controls and derive more robust parameter estimates for Earth system models.

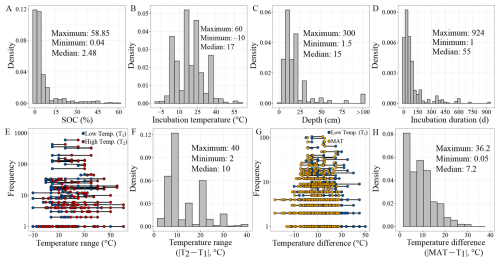

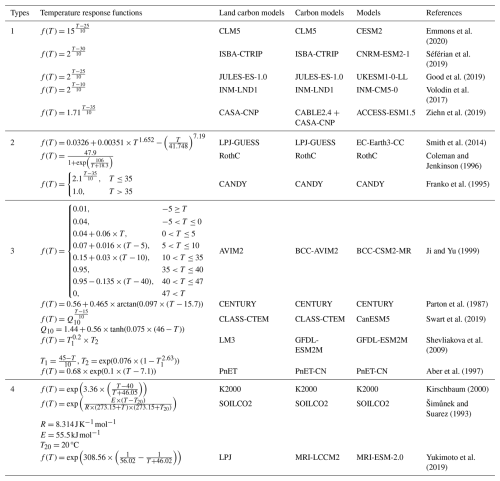

Earth System Models (ESMs) are key tools for projecting SOC dynamics under climate change, yet their predictive accuracy hinges on the reliability of temperature response functions for SOC mineralization. We examined 69 models, including those from the Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) and several widely used carbon models, and identified 16 distinct temperature response functions (Fig. 3; Tables 2 and S1 in the Supplement). These functions differ markedly in structure, particularly at temperatures above 20 °C, where predicted mineralization rates diverge substantially (Fig. 3A). Most functions are empirical in nature and fall into four broad categories (Table 2):

-

Simple exponential models – assume fixed temperature sensitivity (e.g., constant Q10 or classical Arrhenius);

-

Flexible Q10 models – allow Q10 to vary with temperature, typically through parameterized functions;

-

Non-linear empirical models – capture physiological thresholds, saturation effects, or inhibition at high temperatures; and

-

Hybrid/adjusted exponential models – incorporate additional terms to improve empirical fits (e.g., multi-term exponential or polynomial-exponential hybrids).

Figure 3Performance of soil carbon temperature response functions. Temperature response functions of soil organic carbon mineralization (A), temperature sensitivity (Q10) predicted by the temperature response functions (B), and function performance by comparing function predicted and observed Q10 (C). Gray open points in panel (B) represent observed Q10 values at different temperatures, while the black dashed curve shows the best-fit relationship between Q10 and temperature based on locally weighted polynomial regression. Red points indicate the mean values under the corresponding temperatures, and error bars represent one standard error of the observations. Panel (C) compares the observed mean Q10 values at different temperatures with the Q10 values predicted by the temperature response functions, presented for both global average and subsets grouped by ecosystem type. In panel (C), numbers outside the parentheses represent the coefficient of determination (R2), while numbers inside the parentheses indicate the root mean square error. Grey grids represent cases where R2 could not be calculated due to constant Q10 values defined by the respective temperature response functions.

Table 2Temperature response functions used in 69 carbon models. Q10_mod was estimated based on its definition, using the following equation: . Carbon models simulate carbon cycling process and, in some cases, the associated energy and water exchanges, while land carbon models are their submodules specifically representing terrestrial carbon cycling processes.

This diversity reflects both the absence of a mechanistic consensus on temperature sensitivity and the trade-offs between functional realism, parameter interpretability, and computational efficiency.

Across all model types, a consistent feature is the prediction of lower SOC mineralization rates at lower temperatures (Fig. 3A). This conforms with known biological constraints – low temperatures suppress microbial activity and freeze liquid water, thereby restricting substrate diffusion and microbial access. However, substantial uncertainty persists regarding mineralization responses at elevated temperatures. Specifically, the temperature response functions yield three distinct response patterns:

-

Monotonic increase – mineralization rates rise continuously with temperature (e.g., classic Arrhenius behaviour; Fang et al., 2017);

-

Plateau – mineralization rates increase to an asymptote beyond which additional warming has little effect; and

-

Peak followed by decline – mineralization rates increase to an optimum and then drop due to thermal inhibition of enzymes, microbial stress, or substrate exhaustion.

Empirical studies support all three behaviours under different contexts, highlighting the need for flexible models that can accommodate nonlinearities and thresholds in warming responses (Alster et al., 2023).

To evaluate model performance, we calculated observed Q10 (Q10_obs) using Eq. (1) from our global incubation dataset using Eq. (1), and compared them to modelled Q10 values (Q10_mod) derived from each function. Q10_obs was computed for each experiment, then aggregated by incubation temperature (T1) to derive the global mean Q10_obs at each temperature. There were then compared to Q10_mod at corresponding temperatures for each model function (Fig. 3B and C). The results indicate that Q10_obs varies widely but exhibits a nonlinear decline with increasing temperature (Fig. 3B), consistent with metabolic theory and enzyme kinetics (Gillooly et al., 2001). Among the 16 tested functions, Type 4 (hybrid/adjusted exponential) functions performed best, with R2 values of >0.4 and rooted mean square errors (RMSE)<1.2 (Fig. 3C). Type 1 (simple exponential) functions ranked second in performance, while Type 2 (flexible Q10) functions consistently underperformed (R2<0.2). Notably, all functions performed adequately within the 10–30 °C range – where most Q10_obs values clustered around 2 – but were less reliable below 10 °C or above 30 °C (Fig. 3B), where sample sizes were limited and biological responses are less predictable.

Ecosystem-specific performance varied substantially (Figs. 3C and S1 in the Supplement). In forest ecosystems, Type 4 and Type 3 functions performed best, capturing both the magnitude and temperature dependency of Q10_obs, while models such as CLASS-CTEM consistently underpredicted sensitivity. Wetland soils also showed good agreement with most functions (except AVIM2), although the small number of observations and narrow temperature range warrant caution. In croplands and grasslands, Q10_obs values remained relatively stable (∼2) across all temperatures (Fig. S1), likely due to uniform substrate quality, frequent anthropogenic disturbances (e.g., tillage, fertilization), and homogenized microbial communities, which dampen temperature responsiveness. Accordingly, Type 1 models – emphasizing constant Q10 – performed best in these systems. However, data scarcity remains a limiting factor for evaluating model performance in tundra, desert, and high-latitude cold systems. These ecosystems, while storing vast amounts of SOC and being highly sensitive to warming, remain underrepresented in both incubation data and model calibration. Their unique dynamics – driven by freeze–thaw cycles, moisture constraints, and slow microbial turnover – may necessitate tailored temperature response formulations not currently embedded in most ESMs.

Taken together, our results highlight that: (1) no single temperature response function captures Q10_obs variability across all ecosystems and temperature ranges; (2) simple and hybrid exponential functions show relatively robust performance, particularly in cropland, grassland, and forest soils; (3) high-latitude, subsoil, and high-temperature responses remain poorly constrained due to data limitations; (4) expanding observational datasets across diverse ecosystems – especially in extreme environments – is essential for improving the realism and generalizability of temperature response functions in ESMs. Ultimately, our comparison provides a benchmark for refining temperature sensitivity formulations in soil carbon models, emphasizing the need for ecosystem-specific calibration and incorporation of nonlinear temperature effects to reduce uncertainty in future carbon–climate feedback projections.

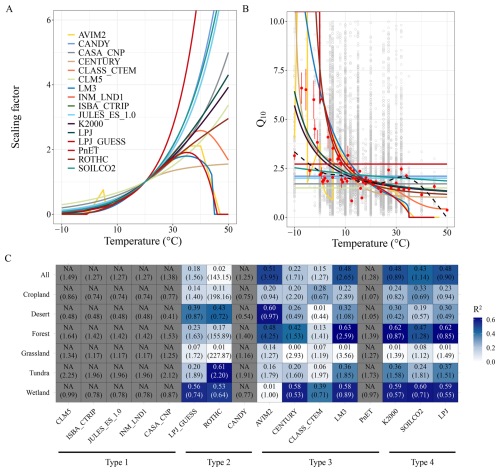

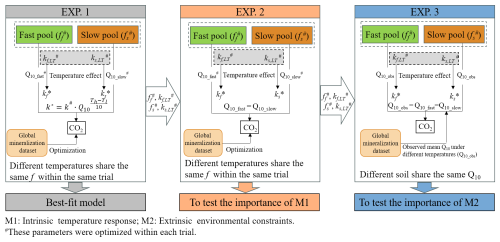

The extensive spatial and environmental coverage of our global SOC mineralization dataset offer a unique opportunity to explore the mechanisms regulating the temperature sensitivity of microbial decomposition. To fully harness this potential, mechanistically-informed modelling approaches are essential. Here, we integrate the dataset with commonly used pool-based carbon models to test the relative contributions of different regulatory mechanisms. SOC mineralization is controlled by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include the chemical decomposability of SOC pools and the thermal traits of microbial communities – collectively referred to as the inherent temperature response (Davidson and Janssens, 2006). These control the baseline temperature dependence of microbial activity and carbon use efficiency. In contrast, extrinsic factors – such as mineral associations, aggregate occlusion, moisture limitation, and oxygen availability – operate as external environmental constraints, restricting microbial access to otherwise decomposable organic matter (Dungait et al., 2012). Separating these two mechanisms is critical, as they operate on different scales and are likely to respond differently to climate change. We propose a modelling framework in which SOC temperature sensitivity is divided into these two components, allowing us to quantify their relative contributions (Fig. 4).

Figure 4The data-model integration framework to distinguish the importance of intrinsic temperature responses and extrinsic environmental constraints. The framework illustrates the data-model fusion process employed to verify the regulatory mechanisms underlying the temperature sensitivity of soil organic carbon mineralization. M1, intrinsic temperature response, associated with the chemical decomposability of SOC pools and the thermal traits of microbial communities; M2, extrinsic environmental constraints, referring to factors such as mineral associations, aggregate occlusion, moisture limitation, and oxygen availability that restrict microbial access to otherwise decomposable organic matter. kf,LT and ks,LT represent the decomposition rates (d−1) of the fast (ff) and slow (fs) carbon pools, respectively at the lowest incubation temperature within the same trial. Q10_fast and Q10_slow are the temperature sensitivity of fast and slow carbon pools, respectively. Th and Tl denote the higher and lower incubation temperature, respectively. In EXP. 1, kf and ks at the lowest temperature of each trial were optimized and then were scaled to other temperatures using Q10_fast and Q10_slow, which were also optimized. The pool size (f) and decomposition rates (kf and ks) at the lowest temperature from EXP. 1 were applied in EXP. 2 and 3.

5.1 A two-pool model of SOC mineralization

To represent SOC heterogeneity and its decomposition dynamics, we adopt a two-pool first-order model, distinguishing between fast- and slow-cycling carbon pools. The mineralization rate Rt () at time t is expressed following Eq. (2):

where kf and ks are the decomposition rate constants (d−1) for the fast and slow pools, respectively; ff is the initial fraction of the fast pool in initial total SOC (C0); t is time in days. Temperature sensitivity is introduced via a Q10 formulation following Eq. (3):

where kT is the decomposition rate of a carbon pool at incubation temperature T (°C); kref is the decomposition rate of the pool at a defined reference temperature (Tref); Q10 is the temperature sensitivity factor.

5.2 Simulation experiments

We conducted three simulation experiments to assess how well different regulatory mechanisms explain the observed temperature sensitivity of SOC mineralization. In all experiments, model parameters were optimized by minimizing RMSE between observed and modeled SOC mineralization rates using the DEoptim package in R4.0.3. Prior parameter ranges were set to 0.1–0.7 for kf, 0–0.01 for ks, and 0–0.2 for ff, following Schädel et al. (2013). A detailed description about the optimization procedure can be found in Zhang et al. (2024).

-

EXP. 1: Best-fit model (full optimization). In this baseline simulation, all model parameters – kf, ks, and ff – were freely optimized for each temperature treatment within each incubation trial. The optimized parameters therefore capture the combined effects of intrinsic substrate-microbe interactions and extrinsic environmental constraints. However, within a given trial, the same ff value was shared across different incubation temperatures to ensure consistent carbon pool partitioning as the same soil was incubated. This “full optimization” represents the best-case model performance and serves as the baseline for comparison.

-

EXP. 2: Inherent temperature response. To isolate the intrinsic component of temperature sensitivity, we fixed the decomposition rates kf and ks and pool size (f) to those optimized at the lowest incubation temperature in EXP. 1. A single optimized Q10 value was then used to scale decomposition rates across higher temperatures using Eq. (3) within each trial. The response of a specific SOC pool to temperature depends on its chemical decomposability and the thermal traits of the associated microbial community. Forcing the temperature sensitivities to be the same (i.e., a single Q10) across carbon pools effectively eliminates these distinct responses, thereby isolating the effect of microbial and substrate-related intrinsic temperature response.

-

EXP. 3: External environmental constraints. In this experiment, kf and ks were again fixed at the values from the lowest incubation temperature, and f values were taken from EXP. 1. Instead of optimizing Q10 for each trial, globally averaged Q10 values (derived from the empirical dataset) were uniformly applied across all soils to scale decomposition rates at higher temperatures. This approach standardizes the inherent temperature sensitivity of SOC decomposition, such that deviation between modeled and observed SOC mineralization rates primarily reflect site-specific external constraints on microbial access to SOC.

Comparing the model performance among EXP. 1–3 allows us to quantify the relative explanatory power of intrinsic and extrinsic regulatory mechanisms. Specifically, reductions in model performance when moving from EXP. 1 to EXP. 2 and from EXP. 2 to EXP. 3 correspond to the contribution of intrinsic and extrinsic effects, respectively. To evaluate the contribution of each mechanism to model performance, we calculated their relative importance following Eqs. (4)–(8) (Grömping, 2007):

where I1 and I2 represent the importance of inherent temperature response and external environmental constraints, respectively; P1 and P2 denote the relative importance of two mechanisms, respectively; Unexplained indicate the unexplained portion of total variation. We applied bootstrap resampling (n=5000) to estimate the mean and 95 % confidence interval (CI) for the relative importance of each mechanism across all incubation trials. For pairwise comparisons among ecosystems and soil depths, the mean difference was calculated for each bootstrap resample, and the 95 % CI of the difference was derived from the bootstrap distribution. A difference was considered statistically significant if the 95 % CI of the bootstrap samples did not include zero (Efron and Tibshirani, 1994).

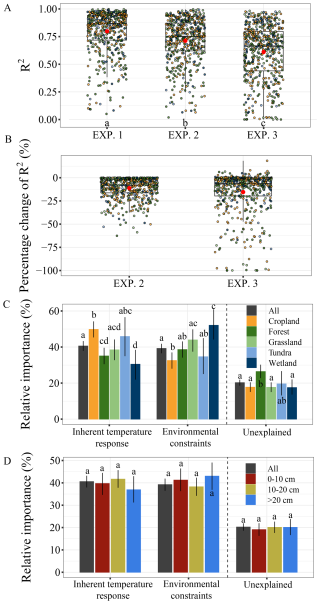

5.3 Simulation results

The modeling experiments revealed distinct contributions of intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms to the temperature sensitivity of SOC mineralization. The model explained, on average, 80 %, 71 %, and 61 % of the variance in SOC mineralization for EXP. 1–EXP. 3, respectively (Fig. 5A). RMSE increased accordingly across the three experiments (Fig. S2). Relative to EXP. 1, model performance in EXP. 2 showed a decline ranging from +0.1 % to −62.6 % with an average of −11.1 %. Relative to EXP. 2, model performance in EXP. 3 exhibited changes from +18.3 % to −99.9 % with an average of −15.4 % (Fig. 5B). Overall, intrinsic temperature response and extrinsic environmental constraints contributed comparably at the global scale, with intrinsic response accounting for 41 % with a 95 % confidence interval (CI) of 38 %–43 % and environmental constraints contributing 39 % (95 % CI: 37 %–42 %) to the total variance (Fig. 5C). However, substantial variation emerged across ecosystems. In croplands, intrinsic temperature response was dominant, contributing 50 % (95 % CI: 45 %–54 %), whereas environmental constraints accounted for a smaller share (33 % with the 95 % CI of 28 %–37 %). In contrast, wetlands exhibited the opposite pattern, with environmental constraints contributing 52 % (95 % CI: 44 %–61 %) and intrinsic temperature response contributing only 30 % (95 % CI: 22 %–38 %).

Figure 5The relative importance of intrinsic temperature responses and external environmental constraints. Panels (A) and (B) show the determination coefficients (R2) and the corresponding percentage changes in R2, respectively, for the three simulation experiments. Panels (C) and (D) represent relative importance of the two mechanisms categorized by ecosystem type and soil depth, respectively. (B) the percentage change in R2 of EXP. 2 relative to EXP. 1, and the percentage change in R2 of EXP. 3 relative to EXP. 2. Error bars in panels (C) and (D) represent the 95 % confidence intervals based on 5000 bootstrap resamples of the original relative importance. EXP. 1 represents the best-fit model and serves as the baseline for comparison, EXP. 2 aims to assess the relative importance of the intrinsic temperature response, and EXP. 3 aims to assess the relative importance of external environmental constraints. Different letters in panels (A), (C), and (D) indicate significant difference (p<0.05).

These contrasting patterns reflect ecosystem-specific controls on the temperature sensitivity of SOC mineralization. In croplands, frequent soil disturbances such as tillage, fertilization, and residue management likely enhance substrate availability and microbial activity, thereby amplifying the role of intrinsic biological and chemical processes (Chen et al., 2019). In wetlands, by contrast, saturated conditions impose strong oxygen limitations and redox constraints on microbial activity, making abiotic environmental factors the primary regulator of SOC turnover (Chen et al., 2018). These findings underscore the importance of incorporating ecosystem-specific mechanisms into ESMs – particularly in systems shaped by hydrological regimes or intensive management – is critical for improving projections of soil carbon–climate feedbacks under global warming.

There were no significant differences of the relative importance of the two regulatory mechanisms across soil depths (Fig. 5D). However, it should be noted that subsoil layers was underrepresented, particularly for layers between 0.5 m (Fig. 2C). Together, our results highlight the importance of integrating both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms into understanding temperature response functions. These case study results underscore the potential of the dataset for facilitating model-data integration, exploring the mechanisms underlying SOC dynamics in response to climate change, and refining model representations under future warming.

However, it is critical to acknowledge that the “intrinsic temperature response” in our modelling framework encompasses both SOC chemical decomposability and microbial metabolic activity, as these processes are inherently intertwined in carbon turnover (Conant et al., 2011). For example, an increase in the decomposition rate constant (k) with temperature could reflect enhanced microbial enzyme kinetics, but may also be driven by temperature-induced changes in substrate availability via increased diffusion or depolymerization of complex carbon compounds (Conant et al., 2011). Similarly, shifts in the fraction of fast-cycling carbon (ff) may not solely indicate a change in carbon pool composition, but also microbial substrate preferences or physiological adjustments that alter carbon allocation between biomass production and respiration (Zheng et al., 2025). These caveats underscore the need for more detailed, trait-explicit models that separately track microbial physiology, substrate quality, and abiotic accessibility (Zhang et al., 2024).

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Figshare at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25808698 (Zhang et al., 2025).

SOC dynamics are central to predicting terrestrial carbon–climate feedbacks, yet remain a major source of uncertainty in ESMs. By synthesizing a comprehensive global dataset of SOC mineralization under controlled incubation conditions, this study provides a robust framework to evaluate the temperature sensitivity of SOC decomposition and the mechanisms that govern it. Our findings highlight that external environmental constraints – such as physicochemical protection and substrate accessibility – and intrinsic SOC decomposability play similarly important roles in shaping temperature responses, but their relative influence is ecosystem-dependent. Moreover, we demonstrate that widely used temperature response functions in carbon models often fail to capture observed patterns, particularly under temperature extremes or in specific ecosystems.

Based on our analyses, we propose following priorities for advancing SOC-climate research:

-

Expand spatial and vertical coverage of soil sampling. Despite the growing number of incubation studies, current datasets remain heavily biased toward surface soils, mid-latitude systems, and short-term incubations. Particularly underrepresented are data from extreme environments (e.g., tundra, wetlands, deserts), subsoil layers, and high or low incubation temperatures – all of which are crucial for understanding carbon–climate feedbacks in vulnerable or carbon-dense regions. Addressing these gaps through targeted sampling campaigns and standardized data collection would enhance model calibration, validation, and transferability across scales.

-

Align incubation design with ecologically relevant temperature scenarios. Laboratory incubation conditions – although valuable for isolating mechanisms – may fail to replicate the complexity of natural systems. Field conditions introduce fluctuating moisture regimes, plant-microbe interactions, freeze-thaw cycles, and other dynamic processes that strongly mediate SOC responses. We advocate for hybrid approaches that combine laboratory incubation data with in situ measurements (e.g., eddy covariance fluxes, carbon isotope tracing) and long-term warming experiments to ground-truth model behaviour and improve ecological relevance.

-

Integrate mechanistic constraints into models. Most SOC temperature response functions currently used in carbon models are based on simplified relationships that fail to incorporate critical regulatory mechanisms. Our findings clearly demonstrate that these simplified functions often underperform when applied to real-world data, particularly across diverse ecosystems and temperature regimes. Embedding mechanistic constraints, such as mineral protection, oxygen limitation, and depth-specific carbon turnover, into temperature response formulations (Bradford et al., 2016) could substantially improve the fidelity of SOC projections under future climate scenarios.

-

Advance spatial scaling. Most carbon models still apply uniform temperature response functions across broad geographic regions, neglecting site-specific variability in soil properties, mineralogy, hydrology, and microbial ecology. Our findings argue for a more spatially explicit representation of SOC temperature responses. Advances in machine learning, data assimilation, and remote sensing provide promising tools for spatial upscaling of temperature response parameters, enabling site-specific calibration of carbon models. Integrating knowledge-guided machine learning with mechanistic soil biogeochemistry models (Liu et al., 2024) would significantly enhance predictive accuracy and reduce uncertainty in regional and global carbon–climate feedback estimates.

Together, these priorities call for a more mechanistic, depth-aware, and spatially explicit framework for investigating SOC mineralization. By coupling empirical datasets with process-based modelling and machine learning, the soil carbon research community can significantly reduce uncertainty in carbon–climate feedbacks and improve projections of SOC stability in a warming world.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-18-131-2026-supplement.

ZL conceived the study; SZ led data collection, assessed the data, and wrote the first draft; ZL revised the manuscript and led results interpretation with the contribution of all authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments, which substantially improved the quality and clarity of this manuscript.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 32171639 and 32241036) and the China National Postdoctoral Program (grant nos. BX20240324 and 2025M782501).

This paper was edited by Giulio G. R. Iovine and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Aber, J. D., Ollinger, S. V., and Driscoll, C. T.: Modeling nitrogen saturation in forest ecosystems in response to land use and atmospheric deposition, Ecol. Model., 101, 61–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(97)01953-4, 1997.

Alster, C. J., Van de Laar, A., Goodrich, J. P., Arcus, V. L., Deslippe, J. R., Marshall, A. J., and Schipper, L. A.: Quantifying thermal adaptation of soil microbial respiration, Nat. Commun., 14, 5459, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41096-x, 2023.

Bradford, M. A., Wieder, W. R., Bonan, G. B., Fierer, N., Raymond, P. A., and Crowther, T. W.: Managing uncertainty in soil carbon feedbacks to climate change, Nat. Clim. Change, 6, 751–758, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3071, 2016.

Burda, B. U., O'Connor, E. A., Webber, E. M., Redmond, N., and Perdue, L. A.: Estimating data from figures with a Web-based program: Considerations for a systematic review, Res. Synth. Methods, 8, 258–262, https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1232, 2017.

Chen, H., Zou, J., Cui, J., Nie, M., and Fang, C.: Wetland drying increases the temperature sensitivity of soil respiration, Soil Biol. Biochem., 120, 24–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.01.035, 2018.

Chen, Z., Xu, Y., Castellano, M. J., Fontaine, S., Wang, W., and Ding, W.: Soil Respiration Components and their Temperature Sensitivity Under Chemical Fertilizer and Compost Application: The Role of Nitrogen Supply and Compost Substrate Quality, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 124, 556–571, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JG004771, 2019.

Coleman, K. and Jenkinson, D.: RothC-26.3A Model for the turnover of carbon in soil, in: Evaluation of soil organic matter models: Using existing long-term datasets, Springer, 237–246, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-61094-3_17, 1996.

Conant, R. T., Ryan, M. G., Ågren, G. I., Birge, H. E., Davidson, E. A., Eliasson, P. E., Evans, S. E., Frey, S. D., Giardina, C. P., and Hopkins, F. M.: Temperature and soil organic matter decomposition rates – synthesis of current knowledge and a way forward, Glob. Change Biol., 17, 3392–3404, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02496.x, 2011.

Craine, J. M., Fierer, N., and McLauchlan, K. K.: Widespread coupling between the rate and temperature sensitivity of organic matter decay, Nat. Geosci., 3, 854–857, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1009, 2010.

Crowther, T. W., Todd-Brown, K. E., Rowe, C. W., Wieder, W. R., Carey, J. C., Machmuller, M. B., Snoek, B., Fang, S., Zhou, G., and Allison, S. D.: Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming, Nature, 540, 104–108, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20150, 2016.

Davidson, E. A. and Janssens, I. A.: Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change, Nature, 440, 165–173, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04514, 2006.

Dungait, J. A. J., Hopkins, D. W., Gregory, A. S., and Whitmore, A. P.: Soil organic matter turnover is governed by accessibility not recalcitrance, Glob. Change Biol., 18, 1781–1796, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02665.x, 2012.

Emmons, L., Schwantes, R., Orlando, J., Tyndall, G., Kinnison, D., Lamarque, J., Marsh, D., Mills, M., Tilmes, S., and Bardeen, C.: The Chemistry Mechanism 590 in the Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2), J. Adv. Model. Earth Sy., 12, e2019MS001882, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001882, 2020.

Fang, Y., Singh, B. P., Matta, P., Cowie, A. L., and Van Zwieten, L.: Temperature sensitivity and priming of organic matter with different stabilities in a Vertisol with aged biochar, Soil Biol. Biochem., 115, 346–356, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.09.004, 2017.

Fick, S. E. and Hijmans, R. J.: WorldClim 2: new 1‐km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas, Int. J. Climatol., 37, 4302–4315, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086, 2017.

Fierer, N., Colman, B. P., Schimel, J. P., and Jackson, R. B.: Predicting the temperature dependence of microbial respiration in soil: A continental-scale analysis, Glob. Biogeochem. Cy., 20, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002644, 2006.

Franko, U., Oelschlägel, B., and Schenk, S.: Simulation of temperature-, water- and nitrogen dynamics using the model CANDY, Ecol. Model., 81, 213–222, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3800(94)00172-E, 1995.

Georgiou, K., Koven, C. D., Wieder, W. R., Hartman, M. D., Riley, W. J., Pett-Ridge, J., Bouskill, N. J., Abramoff, R. Z., Slessarev, E. W., and Ahlström, A.: Emergent temperature sensitivity of soil organic carbon driven by mineral associations, Nat. Geosci., 17, 205–212, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01384-7, 2024.

Gershenson, A., Bader, N. E., and Cheng, W.: Effects of substrate availability on the temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition, Glob. Change Biol., 15, 176–183, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01827.x, 2009.

Gillooly, J. F., Brown, J. H., West, G. B., Savage, V. M., and Charnov, E. L.: Effects of Size and Temperature on Metabolic Rate, Science, 293, 2248–2251, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1061967, 2001.

Good, P., Sellar, A., Tang, Y., Rumbold, S., Ellis, R., Kelley, D., and Kuhlbrodt, T.: MOHC UKESM1.0-LL model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp585, https://doi.org/10.22033/esgf/cmip6.6405, 2019.

Grömping, U.: Relative importance for linear regression in R: the package relaimpo, J. Stat. Softw., 17, 1–27, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v017.i01, 2007.

Guan, X., Jiang, J., Jing, X., Feng, W., Luo, Z., Wang, Y., Xu, X., and Luo, Y.: Optimizing duration of incubation experiments for understanding soil carbon decomposition, Geoderma, 428, 116225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.116225, 2022.

Haaf, D., Six, J., and Doetterl, S.: Global patterns of geo-ecological controls on the response of soil respiration to warming, Nat. Clim. Change, 11, 623–627, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01068-9, 2021.

Haddix, M. L., Plante, A. F., Conant, R. T., Six, J., Steinweg, J. M., Magrini-Bair, K., Drijber, R. A., Morris, S. J., and Paul, E. A.: The role of soil characteristics on temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 75, 56–68, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2010.0118, 2011.

Hamdi, S., Moyano, F., Sall, S., Bernoux, M., and Chevallier, T.: Synthesis analysis of the temperature sensitivity of soil respiration from laboratory studies in relation to incubation methods and soil conditions, Soil Biol. Biochem., 58, 115–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.11.012, 2013.

Hartley, I. P., Hill, T. C., Chadburn, S. E., and Hugelius, G.: Temperature effects on carbon storage are controlled by soil stabilisation capacities, Nat. Commun., 12, 6713, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27101-1, 2021.

Hicks Pries, C. E., Castanha, C., Porras, R., and Torn, M.: The whole-soil carbon flux in response to warming, Science, 355, 1420–1423, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1319, 2017.

Hicks Pries, C. E., Ryals, R., Zhu, B., Min, K., Cooper, A., Goldsmith, S., Pett-Ridge, J., Torn, M., and Berhe, A. A.: The deep soil organic carbon response to global change, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. S., 54, 375–401, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102320-085332, 2023.

IPCC: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, Lee, H. and Romero, J. (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001, 2023.

Ji, J. and Yu, L.: A simulation study of coupled feedback mechanism between physical and biogeochemical processes at the surface, Chin. J. Atmos. Sci., 23, 448–459, https://doi.org/10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.1999.04.07, 1999.

Jia, J., Cao, Z., Liu, C., Zhang, Z., Lin, L., Wang, Y., Haghipour, N., Wacker, L., Bao, H., and Dittmar, T.: Climate warming alters subsoil but not topsoil carbon dynamics in alpine grassland, Glob. Change Biol., 25, 4383–4393, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14823, 2019.

Jobbágy, E. G. and Jackson, R. B.: The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation, Ecol. Appl., 10, 423–436, https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[0423:TVDOSO]2.0.CO;2, 2000.

Jones, C. D., Cox, P., and Huntingford, C.: Uncertainty in climate'carbon-cycle projections associated with the sensitivity of soil respiration to temperature, Tellus B, 55, 642–648, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v55i2.16760, 2003.

Karhu, K., Auffret, M. D., Dungait, J. A., Hopkins, D. W., Prosser, J. I., Singh, B. K., Subke, J.-A., Wookey, P. A., Ågren, G. I., and Sebastia, M.-T.: Temperature sensitivity of soil respiration rates enhanced by microbial community response, Nature, 513, 81–84, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13604, 2014.

Kirschbaum, M. U.: Will changes in soil organic carbon act as a positive or negative feedback on global warming?, Biogeochemistry, 48, 21–51, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006238902976, 2000.

Kirschbaum, M. U. F.: The temperature dependence of organic-matter decomposition – still a topic of debate, Soil Biol. Biochem., 38, 2510–2518, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.01.030, 2006.

Lei, J., Guo, X., Zeng, Y., Zhou, J., Gao, Q., and Yang, Y.: Temporal changes in global soil respiration since 1987, Nat. Commun., 12, 403, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20616-z, 2021.

Li, J., Pei, J., Pendall, E., Fang, C., and Nie, M.: Spatial heterogeneity of temperature sensitivity of soil respiration: A global analysis of field observations, Soil Biol. Biochem., 141, 107675, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.107675, 2020.

Liu, L., Zhou, W., Guan, K., Peng, B., Xu, S., Tang, J., Zhu, Q., Till, J., Jia, X., Jiang, C., Wang, S., Qin, Z., Kong, H., Grant, R., Mezbahuddin, S., Kumar, V., and Jin, Z.: Knowledge-guided machine learning can improve carbon cycle quantification in agroecosystems, Nat. Commun., 15, 357, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43860-5, 2024.

Luo, Y., Ahlström, A., Allison, S. D., Batjes, N. H., Brovkin, V., Carvalhais, N., Chappell, A., Ciais, P., Davidson, E. A., and Finzi, A.: Toward more realistic projections of soil carbon dynamics by Earth system models, Glob. Biogeochem. Cy., 30, 40–56, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GB005239, 2016.

Luo, Z., Luo, Y., Wang, G., Xia, J., and Peng, C.: Warming-induced global soil carbon loss attenuated by downward carbon movement, Glob. Change Biol., 26, 7242–7254, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15370, 2020.

Melillo, J. M., Frey, S. D., DeAngelis, K. M., Werner, W. J., Bernard, M. J., Bowles, F. P., Pold, G., Knorr, M. A., and Grandy, A. S.: Long-term pattern and magnitude of soil carbon feedback to the climate system in a warming world, Science, 358, 101–105, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan2874, 2017.

Parton, W. J., Schimel, D. S., Cole, C. V., and Ojima, D. S.: Analysis of factors controlling soil organic matter levels in Great Plains grasslands, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 51, 1173–1179, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1987.03615995005100050015x, 1987.

Patel, K. F., Bond-Lamberty, B., Jian, J., Morris, K. A., McKever, S. A., Norris, C. G., Zheng, J., and Bailey, V. L.: Carbon flux estimates are sensitive to data source: a comparison of field and lab temperature sensitivity data, Environ. Res. Lett., 17, 113003, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac9aca, 2022.

Ren, S., Ding, J., Yan, Z., Cao, Y., Li, J., Wang, Y., Liu, D., Zeng, H., and Wang, T.: Higher temperature sensitivity of soil C release to atmosphere from northern permafrost soils as indicated by a meta-analysis, Glob. Biogeochem. Cy., 34, e2020GB006688, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GB006688, 2020.

Schädel, C., Luo, Y., David Evans, R., Fei, S., and Schaeffer, S. M.: Separating soil CO2 efflux into C-pool-specific decay rates via inverse analysis of soil incubation data, Oecologia, 171, 721–732, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-012-2577-4, 2013.

Schädel, C., Beem-Miller, J., Aziz Rad, M., Crow, S. E., Hicks Pries, C. E., Ernakovich, J., Hoyt, A. M., Plante, A., Stoner, S., Treat, C. C., and Sierra, C. A.: Decomposability of soil organic matter over time: the Soil Incubation Database (SIDb, version 1.0) and guidance for incubation procedures, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 1511–1524, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-1511-2020, 2020.

Schmidt, M. W. I., Torn, M. S., Abiven, S., Dittmar, T., Guggenberger, G., Janssens, I. A., Kleber, M., Kögel-Knabner, I., Lehmann, J., Manning, D. A. C., Nannipieri, P., Rasse, D. P., Weiner, S., and Trumbore, S. E.: Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property, Nature, 478, 49–56, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10386, 2011.

Schuur, E. A., Vogel, J. G., Crummer, K. G., Lee, H., Sickman, J. O., and Osterkamp, T.: The effect of permafrost thaw on old carbon release and net carbon exchange from tundra, Nature, 459, 556–559, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08031, 2009.

Séférian, R., Nabat, P., Michou, M., Saint-Martin, D., Voldoire, A., Colin, J., Decharme, B., Delire, C., Berthet, S., and Chevallier, M.: Evaluation of CNRM Earth system model, CNRM-ESM2–1: Role of Earth system processes in present-day and future climate, J. Adv. Model. Earth Sy., 11, 4182–4227, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001791, 2019.

Shevliakova, E., Pacala, S. W., Malyshev, S., Hurtt, G. C., Milly, P., Caspersen, J. P., Sentman, L. T., Fisk, J. P., Wirth, C., and Crevoisier, C.: Carbon cycling under 300 years of land use change: Importance of the secondary vegetation sink, Glob. Biogeochem. Cy., 23, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GB003176, 2009.

Šimůnek, J. and Suarez, D. L.: Modeling of carbon dioxide transport and production in soil: 1. Model development, Water Resour. Res., 29, 487–497, https://doi.org/10.1029/92WR02225, 1993.

Smith, B., Wårlind, D., Arneth, A., Hickler, T., Leadley, P., Siltberg, J., and Zaehle, S.: Implications of incorporating N cycling and N limitations on primary production in an individual-based dynamic vegetation model, Biogeosciences, 11, 2027–2054, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-2027-2014, 2014.

Soong, J. L., Castanha, C., Hicks Pries, C. E., Ofiti, N., Porras, R. C., Riley, W. J., Schmidt, M. W., and Torn, M. S.: Five years of whole-soil warming led to loss of subsoil carbon stocks and increased CO2 efflux, Sci. Adv., 7, eabd1343, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd1343, 2021.

Swart, N. C., Cole, J. N. S., Kharin, V. V., Lazare, M., Scinocca, J. F., Gillett, N. P., Anstey, J., Arora, V., Christian, J. R., Hanna, S., Jiao, Y., Lee, W. G., Majaess, F., Saenko, O. A., Seiler, C., Seinen, C., Shao, A., Sigmond, M., Solheim, L., von Salzen, K., Yang, D., and Winter, B.: The Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5.0.3), Geosci. Model Dev., 12, 4823–4873, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-4823-2019, 2019.

Tang, X., Fan, S., Du, M., Zhang, W., Gao, S., Liu, S., Chen, G., Yu, Z., and Yang, W.: Spatial and temporal patterns of global soil heterotrophic respiration in terrestrial ecosystems, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 1037–1051, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-1037-2020, 2020.

Efron, B. and Tibshirani, R. J.: An introduction to the bootstrap, New York: Chapman&Hall/CRC, https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429246593, 1994.

Turetsky, M. R., Abbott, B. W., Jones, M. C., Anthony, K. W., Olefeldt, D., Schuur, E. A., Grosse, G., Kuhry, P., Hugelius, G., and Koven, C.: Carbon release through abrupt permafrost thaw, Nat. Geosci., 13, 138–143, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0526-0, 2020.

Volodin, E., Mortikov, E., Kostrykin, S., Galin, V. Y., Lykossov, V., Gritsun, A., Diansky, N., Gusev, A., and Iakovlev, N.: Simulation of the present-day climate with the climate model INMCM5, Clim. Dynam., 49, 3715–3734, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3539-7, 2017.

Wang, C., Morrissey, E. M., Mau, R. L., Hayer, M., Piñeiro, J., Mack, M. C., Marks, J. C., Bell, S. L., Miller, S. N., and Schwartz, E.: The temperature sensitivity of soil: microbial biodiversity, growth, and carbon mineralization, ISME J., 15, 2738–2747, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-00959-1, 2021.

Wang, M., Guo, X., Zhang, S., Xiao, L., Mishra, U., Yang, Y., Zhu, B., Wang, G., Mao, X., and Qian, T.: Global soil profiles indicate depth-dependent soil carbon losses under a warmer climate, Nat. Commun., 13, 5514, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33278-w, 2022.

Wang, Q., Zhao, X., Chen, L., Yang, Q., Chen, S., and Zhang, W.: Global synthesis of temperature sensitivity of soil organic carbon decomposition: Latitudinal patterns and mechanisms, Funct. Ecol., 33, 514–523, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13256, 2019.

Wang, Y., Wang, H., He, J.-S., and Feng, X.: Iron-mediated soil carbon response to water-table decline in an alpine wetland, Nat. Commun., 8, 15972, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15972, 2017.

Xiao, K.-Q., Zhao, Y., Liang, C., Zhao, M., Moore, O. W., Otero-Fariña, A., Zhu, Y.-G., Johnson, K., and Peacock, C. L.: Introducing the soil mineral carbon pump, Nat. Rev. Earth Env., 4, 135–136, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-023-00396-y, 2023.

Xu, M., Li, X., Kuyper, T. W., Xu, M., Li, X., and Zhang, J.: High microbial diversity stabilizes the responses of soil organic carbon decomposition to warming in the subsoil on the Tibetan Plateau, Glob. Change Biol., 27, 2061–2075, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15553, 2021.

Yukimoto, S., Kawai, H., Koshiro, T., Oshima, N., Yoshida, K., Urakawa, S., Tsujino, H., Deushi, M., Tanaka, T., and Hosaka, M.: The Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model version 2.0, MRI-ESM2. 0: Description and basic evaluation of the physical component, J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II, 97, 931–965, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2019-051, 2019.

Zhang, S., Yu, Z., Lin, J., and Zhu, B.: Responses of soil carbon decomposition to drying-rewetting cycles: a meta-analysis, Geoderma, 361, 114069, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.114069, 2020.

Zhang, S., Wang, M., Xiao, L., Guo, X., Zheng, J., Zhu, B., and Luo, Z.: Reconciling carbon quality with availability predicts temperature sensitivity of global soil carbon mineralization, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 121, e2313842121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2313842121, 2024.

Zhang, S., Wang, M., Zheng, J., and Luo, Z.: A global dataset of soil organic carbon mineralization in response to incubation temperature changes, Figshare [data set], https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25808698, 2025.

Zheng, J., van Groenigen, K. J., Hartley, I. P., Xue, R., Wang, M., Zhang, S., Sun, T., Yu, W., Ma, B., Luo, Y., Shi, Z., and Luo, Z.: Temperature sensitivity of bacterial species-level preferences of soil carbon pools, Geoderma, 456, 117268, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2025.117268, 2025.

Ziehn, T., Chamberlain, M., Lenton, A., Law, R., Bodman, R., Dix, M., Wang, Y., Dobrohotoff, P., Srbinovsky, J., and Stevens, L.: CSIRO ACCESS-ESM1. 5 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP, https://doi.org/10.22033/esgf/cmip6.4333, 2019.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The Data

- Insights from the Dataset

- Comparison with Temperature Response Functions

- Combining the Data with Carbon Models

- Data availability

- Conclusions and Future Vision

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The Data

- Insights from the Dataset

- Comparison with Temperature Response Functions

- Combining the Data with Carbon Models

- Data availability

- Conclusions and Future Vision

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement