the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

An 800 kyr planktonic δ18O stack for the Western Pacific Warm Pool

Christen L. Bowman

Devin S. Rand

Lorraine E. Lisiecki

Samantha C. Bova

The Western Pacific Warm Pool (WPWP) exhibits different glacial–interglacial climate variability compared to high latitudes, and its sea surface temperatures are thought to respond primarily to changes in greenhouse forcing. To better characterize the orbital-scale climate response covering the WPWP, we constructed a planktonic δ18O stack (average) of 10 previously published WPWP records of the last 800 kyr, available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10211900 (Bowman et al., 2023), using the new Bayesian alignment and stacking software BIGMACS (Lee et al., 2023b). Similarities in stack uncertainty between the WPWP planktonic δ18O stack and benthic δ18O stacks, also constructed using BIGMACS, demonstrate that the software performs similarly well when aligning regional planktonic or benthic δ18O data. A total of 65 radiocarbon dates from the upper portion of five of the WPWP cores suggest that WPWP planktonic δ18O change is nearly synchronous with global benthic δ18O during the last glacial termination. However, the WPWP planktonic δ18O stack exhibits a smaller glacial–interglacial amplitude and less spectral power at all orbital frequencies than benthic δ18O. We assert that the WPWP planktonic δ18O stack provides a useful representation of orbital-scale regional climate response and a valuable regional alignment target, particularly over the 0 to 450 ka portion of the stack.

- Article

(4536 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(640 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The tropical Pacific is an important source of heat and moisture to the atmosphere (e.g., De Deckker, 2016; Neale and Slingo, 2003; Mayer et al., 2014) and is thought to have a strong impact on global climate responses during glacial cycles (Lea et al., 2000). Prior studies suggest that the climate of the Western Pacific Warm Pool (WPWP), which is defined by mean annual sea surface temperatures (SSTs) above 28 ∘C, responds primarily to changes in greenhouse gas concentrations due to the region's large distance from high-latitude ice sheets (Broccoli, 2000; Lea, 2004; Tachikawa et al., 2014). Additionally, Earth's orbital cycles cause seasonal variations in insolation or incoming solar radiation, which affect Earth's high and low latitudes differently. In the WPWP, only 0.3 ∘C of SST change is attributed to orbital forcing during the late Pleistocene (Tachikawa et al., 2014). Thus, climate records of the WPWP region are expected to have features which differ from the high-latitude climate records often used to describe global climate change (e.g., Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Past Interglacials Working Group of PAGES, 2016). Here we seek to characterize WPWP climate on orbital timescales and its differences from high-latitude climate, which can help test hypotheses about the sensitivity of the WPWP to orbital forcing, ice volume, and greenhouse gas concentration.

One of the most commonly used paleoceanographic climate proxies is the ratio of oxygen isotopes, denoted as δ18O, in calcium carbonate from foraminiferal tests; this proxy is affected by both water temperature and the δ18O of seawater, which varies with global ice volume as well as local salinity (Wefer and Berger, 1991). The two general types of foraminifera are benthic and planktonic, which live in the deep ocean and surface ocean, respectively. Benthic δ18O is considered a high-latitude climate proxy because deep-water temperature is set in high-latitude deep-water formation regions and because global ice volume responds primarily to high-latitude Northern Hemisphere summer insolation. However, planktonic δ18O is influenced by both high-latitude ice volume and local SST and salinity (Rosenthal et al., 2003). Previous studies from the WPWP have shown smaller glacial–interglacial amplitudes of planktonic δ18O change than in benthic δ18O or planktonic δ18O from other regions (Lea et al., 2000; de Garidel-Thoron et al., 2005a). This difference has been attributed to smaller sea surface temperature fluctuations and salinity changes in the WPWP (Broccoli, 2000; Lea et al., 2000; de Garidel-Thoron et al., 2005a).

Here we present a stack (time-dependent average) of planktonic δ18O records from 10 cores across the WPWP to provide a record of its regional responses over the past 800 kyr, which can be compared to the high-latitude response of global and regional benthic δ18O stacks. The WPWP planktonic δ18O stack is intended to better characterize orbital responses in WPWP planktonic δ18O and to improve age models for WPWP sediment cores. Age models for ocean sediment cores, which provide estimates of sediment age as a function of core depth, are commonly constructed by stratigraphic correlation (i.e., alignment) of an individual core's δ18O record to a global δ18O stack such as the LR04 or SPECMAP stacks (Linsley and von Breymann, 1991; Lea et al., 2000; Chuang et al., 2018; Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Imbrie et al., 1984). A stack is the time-dependent average of data from multiple ocean sediment cores that share a common climatic signal, thus increasing the signal-to-noise ratio of the data. Traditionally, stacks have been constructed from global compilations of benthic δ18O (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005), planktonic δ18O (Shakun et al., 2015), or a combination of the two (Imbrie et al., 1984; Huybers and Wunsch, 2004). However, recent studies have advocated the development of regional stacks (Lisiecki and Stern, 2016; Lee et al., 2023a) to distinguish spatial differences in the timing and amplitude of δ18O changes.

We constructed a WPWP planktonic δ18O stack spanning 0 to 800 ka using new Bayesian alignment and stacking software, BIGMACS (Lee et al., 2023b). The new stack consists of previously published planktonic δ18O data and 65 radiocarbon dates ranging from 1.5 to 36.9 ka from 10 cores within the WPWP. We present the new WPWP stack as well as a brief comparison of orbital power in the new stack compared to the LR04 global benthic δ18O stack (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005) and a recently published stack of regional SST (Jian et al., 2022). We also evaluate the relative timing of WPWP planktonic δ18O change versus benthic δ18O change during the last glacial termination.

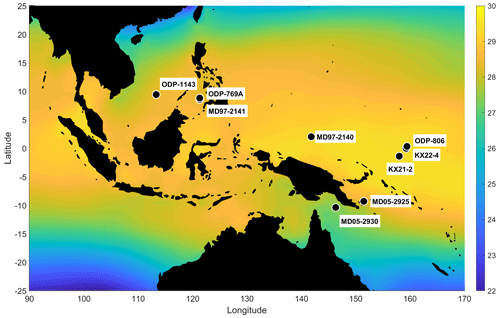

The Western Pacific Warm Pool is a region of the equatorial Pacific with annual average SST between 28 and 30 ∘C (Tachikawa et al., 2014). It covers an area between approximately 15∘ S and 15∘ N and between 115 and 160∘ E (Locarnini et al., 2018). Synchronous change in δ18O is assumed during the stacking procedure (Lee et al., 2023a), so homogeneous conditions in the core locations are important for maintaining the accuracy of the stack. The largely homogeneous WPWP surface ocean makes it a suitable choice for stacking (Lea et al., 2000; Li et al., 2011).

Cores were selected for inclusion based on their location in or near the WPWP, including two cores just beyond the boundary of the typically defined WPWP region. We choose to include these two cores (ODP-1143 and MD05-2930) because of their high resolution and/or an age range that covers the full length of the stack. The cores' locations exhibit oceanographic variability broadly comparable to that observed within the warm pool proper over the period of interest. Core ODP-1143 from the South China Sea, which lies just beyond the northwestern border of the modern WPWP, has an average annual temperature of ∼28 ∘C and receives northward-flowing water from the WPWP during summer (Li et al., 2011). Core MD05-2930 is located along the southern limit of the WPWP in the Gulf of Papua; its SST is primarily controlled by the Australasian monsoon, with modern SST fluctuating between 26 and 29 ∘C (Regoli et al., 2015). The slightly cooler sea surface temperatures of these two cores are expected to yield slightly more positive δ18O values than other WPWP sites; these sites may also be sensitive to orbital-scale changes in the WPWP extent.

To evaluate the contribution of temperature to planktonic δ18O change in the WPWP, we use an Indo-Pacific Warm Pool (IPWP) SST stack (Jian et al., 2022). The IPWP has significant overlap with the WPWP but additionally includes a portion of the Indian Ocean; however, the cores in the Jian et al. (2022) stack are predominantly from the WPWP. The IPWP and WPWP have a mean annual SST of 28 and 29 ∘C, respectively (Locarnini et al., 2018).

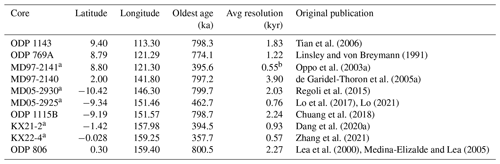

We compiled previously published planktonic δ18O measurements from 10 tropical western Pacific cores in or near the WPWP (Fig. 1, Table 1). Cores were included in the stack based on their location in the WPWP, an age range spanning at least three glacial cycles, and an average time resolution of at least 4 kyr. Four cores span the last 350 to 500 kyr, and six extend back to at least 750 ka (Fig. 2). All but one core in the stack use δ18O values measured from the planktonic species Globigerinoides ruber (G. ruber) sensu stricto (s.s.), whose depth habitat in the WPWP ranges from the upper 45 to 105 m of the mixed layer depending on how calcification depth is calculated (Hollstein et al., 2017). One core, ODP 1115B, has data from a different planktonic species, Trilobatus sacculifer (formerly Globigerinoides sacculifer) whose depth habitat is 20 to 75 m or potentially as deep as 45 to 95 m (Sadekov et al., 2009; Hollstein et al., 2017). A species correction of −0.11 ‰ was applied to the T. sacculifer data according to the values presented by Spero et al. (2003). The average mixed layer depth of the WPWP is 50 to 100 m (Locarnini et al., 2018).

A total of 4762 planktonic δ18O measurements were used to create the stack. The stack spans from 0 to 800 ka; however, there is a significant decrease in data density at 450 ka. Only six cores extend beyond 450 ka, and this portion of the stack is composed of only 960 data points. The lower data resolution results in greater uncertainty and smoothness for the δ18O features in the older portion of the stack; therefore, we focus our analysis of the stack on the 0 to 450 ka portion.

The stacking algorithm counts each δ18O measurement equally, so cores with higher resolution have more influence on the stack. The mean sample spacing in the core records used to create the stack ranges from 0.55 to 3.9 kyr, with greater average sample spacing for the long cores that extend to the older half of the stack. Published data for core MD97-2141 have an average sedimentation rate of 5–15 cm yr−1 and are sampled at 1 cm intervals with a mean sample spacing of 0.11 kyr (Oppo et al., 2003b). However, we smoothed the data using a five-point running mean sampled every fifth point, which increases its mean sample spacing to 0.55 kyr so that this one record does not overly dominate the regional stack. Additionally, we constrain the stack age model using 65 previously published radiocarbon measurements ranging from 1.52 to 36.9 ka from five cores (Oppo et al., 2003a; Regoli et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2017; Dang et al., 2020a; Zhang et al., 2021).

Table 1Locations of cores in the WPWP stack and the temporal coverage of their planktonic δ18O data.

a Core with radiocarbon data; b new resolution after smoothing

Figure 2Planktonic δ18O data from the cores used in the WPWP stack, plotted on BIGMACS age models for each core and offset vertically. Data are from sites ODP-1143 (Tian et al., 2006), ODP-769A (Linsley and von Breymann, 1991), MD97-2141 (Oppo et al., 2003b), MD05-2140 (de Garidel-Thoron et al., 2005b), MD05-2930 (Regoli et al., 2015), MD05-2925 (Lo et al., 2017; Lo, 2021), ODP-1115B (Chuang et al., 2019), KX21-2 (Dang et al., 2020b), KX22-4 (Zhang et al., 2021), and ODP-806 (Lea et al., 2000; Medina-Elizalde and Lea, 2005).

4.1 Stack construction

We use the new Bayesian software package BIGMACS to construct the WPWP planktonic δ18O stack (Lee et al., 2023b). BIGMACS, which stands for Bayesian Inference Gaussian process regression and Multiproxy Alignment for Continuous Stacks, constructs multiproxy age models and stacks by combining age information from both direct age constraints (e.g., radiocarbon data) and probabilistic alignments of δ18O to a target record. Although BIGMACS was developed for benthic δ18O, here we use BIGMACS to align and stack planktonic δ18O; thus, we present an analysis to verify the performance of the software for this new application.

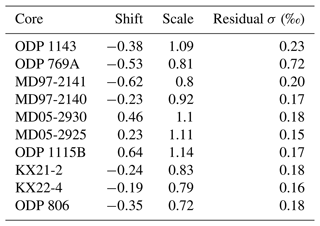

BIGMACS stack construction is an iterative process with two steps. In the first step, age models are estimated for each record by aligning to an initial target. Each δ18O record is shifted and scaled to better match the target stack during alignment, and likelihoods assigned to age estimates for each core depth are based on residuals between the core's shifted and scaled δ18O value and the target's time-dependent mean and standard deviation. In the second step, a stack is constructed with a Gaussian process regression over all δ18O data using the aligned age models, and the stack's mean and amplitude are set to match the average values of the component records. The new stack is then used as the alignment target to construct age models for the next iteration, with alignment parameters updated to maximize likelihood using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm. Iterations are performed until convergence. Core-specific shift and scale parameters (Table 2) reflect how much each individual record differs from the stack based on the assumption that all records share the same underlying signal but allowing for some scaling or offset based on consistent temperature–salinity gradients within the region as well as foraminiferal species differences (vital effects and depth habitat). Nearly homogeneous planktonic δ18O values between cores (and similar to the final stack) are indicated by shift parameters close to 0 and scale parameters close to 1.

The initial alignment target we used for constructing the WPWP stack was the LR04 stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005) with a constant standard deviation of 0.5 ‰. The original age model for the LR04 stack was created by orbital tuning to a simple ice volume model and has estimated age uncertainties of ±4 kyr for the past 800 kyr (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005). Despite the age uncertainty of the LR04 stack and the fact that it reflects benthic rather than planktonic δ18O, it was chosen as the initial alignment target because it is a widely used age model that spans the full 800 kyr time range of the new WPWP stack. Because the stack alignment target is shifted and scaled to match its component records during each iteration, the final stack output by BIGMACS reflects the average WPWP planktonic δ18O values rather than the benthic δ18O values of the initial target.

Importantly, BIGMACS assumes that all records in the stack are homogeneous, i.e., that they all share the same underlying signal (with allowance for site-specific shift and scale values). Under this assumption, all residuals between individual δ18O measurements and the stack are assumed to reflect variability associated with sampling noise, measurement uncertainty, and/or alignment uncertainty. Therefore, when stacking with BIGMACS, it is important to choose records for inclusion in the stack that share the same regional influence. Additionally, because all measurements are treated equally, cores with higher-resolution data are more strongly weighted in the stack construction. The stack uncertainty reported by BIGMACS is the time-dependent standard deviation of a Gaussian fit to the δ18O residuals. To evaluate whether the assumption of homogeneity used by BIGMACS for stack construction is applicable to the WPWP planktonic δ18O records in our new stack, Sect. 6.2 compares the WPWP planktonic stack uncertainty and the average alignment uncertainty of the stacked records to results from previously published regional benthic δ18O stacks.

4.2 Stack age constraints

The first 37 kyr of the WPWP is constrained by 65 radiocarbon dates from five cores. We calibrated radiocarbon ages using the Marine20 calibration curve, which uses a model estimate of time-dependent global mean surface reservoir age, with values of ∼400 years in the Holocene and 800 to 1000 years from 20 to 50 ka (Heaton et al., 2020). We set the reservoir age offset (ΔR) for our sites to 0 years, meaning we did not change the sites' reservoir ages from the time-dependent Marine20 default. We assigned a 1σ uncertainty of 200 years to the reservoir ages to account for possible changes to the reservoir age offset of the WPWP relative to the Marine20 time-dependent global mean reservoir age. Ages for the remainder of the stack are largely determined by the timing of glacial cycles in the LR04 stack. Thus, the timing of planktonic δ18O change in the WPWP stack is assumed to be synchronous with the LR04 benthic stack. In Sect. 6.1, we show that there is strong agreement in the timing of planktonic and benthic δ18O change within WPWP cores and between two benthic stacks from 1.5 to 37 ka, the interval for which WPWP ages are predominantly determined by radiocarbon data.

Core age models were also constrained by age estimates for the first and last δ18O measurement from each core based on previous publications. Because these previous age estimates were based on a variety of methods, they were assigned a Gaussian uncertainty with a relatively large standard deviation of 4 kyr. Additionally, we added tie points for two cores (ODP-1115B at 75 ka and MD97-2141 at 63 and 92.5 ka) to improve the alignment of Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 3 and 4 to the target stack. Because these tie points were assigned based on identification of stratigraphic features in these two cores compared directly to the target stack, we assigned these age estimates a smaller standard deviation of 1 kyr.

4.3 Conversions of SST and sea level to isotopic equivalents

We compare the amplitude of the new WPWP planktonic δ18O stack with a sea level (ice volume) record and an IPWP SST stack, each of which is converted to the amount of planktonic δ18O change they are expected to produce. The global sea level stack of Spratt and Lisiecki (2016) was used to calculate an equivalent change in seawater δ18O due to ice volume (Δδ18Oice) using a conversion of 0.009 ‰ per meter of sea level. This conversion represents the long-term average effect of ice volume change because the size of the effect varies slightly depending on the average δ18O composition of the ice (Spratt and Lisiecki, 2016).

The IPWP SST stack from Jian et al. (2022) was converted to an δ18O equivalent using Eq. (1).

The 4.8 scaling factor is taken from Bemis et al. (1998). A shift of 29 was chosen to express the effects of SST change relative to a modern WPWP mean SST of 29 ∘C. Thus, the resulting Δδ18OSST measures change relative to mean annual SST of the WPWP from 1955–2018 (Locarnini et al., 2018).

4.4 Spectral analysis

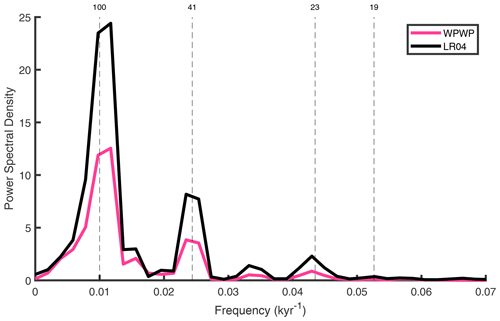

Power spectral density was calculated to quantify the strengths of response to orbital frequencies in δ18O for the WPWP and LR04 stacks. Both stacks were subsampled at 1 kyr spacing from 0 to 800 ka, and power spectral density was calculated using the multitaper power spectral density estimate function pmtm in MATLAB, with the number of tapers set to two, a rate of one sample per kyr, and an nfft of 512 (The MathWorks Inc., 2023). Frequencies corresponding to the orbital cycle lengths of eccentricity (100 kyr), obliquity (41 kyr), and precession (23 and 19 kyr) are of particular interest to see how the insolation changes from the cycles affect the δ18O values.

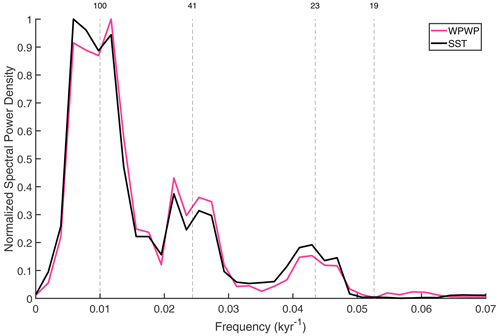

Normalized power spectral density was also calculated using the same method and subsampling for the IPWP SST stack and our WPWP δ18O stack from 0 to 360 ka to match the age range of the SST stack (Jian et al., 2022). The power spectral density of each record was normalized by dividing by the maximum peak height of the dominant ∼100 kyr glacial cycle to evaluate the relative strength of different orbital frequencies.

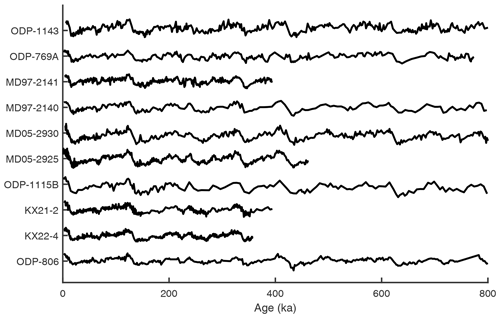

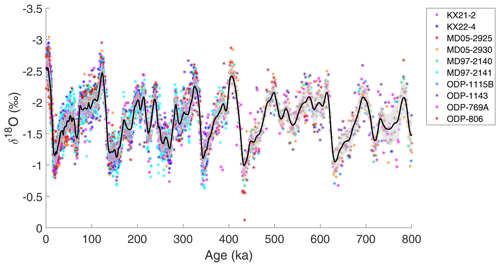

The probabilistic stack created by BIGMACS models the planktonic δ18O value of the WPWP at any point in time as a Gaussian distribution with a time-varying mean and standard deviation (Fig. 3). BIGMACS also estimates and applies shift and scale parameters for each core to optimize fit with the stack (Table 2). The standard deviation of the stack reflects scatter in the shifted and scaled δ18O measurements at each point in time, including the effects of statistical uncertainty in each core's age model. The standard deviation of the stack does not include any information about absolute age uncertainty (outside the range of radiocarbon). However, uncertainty does increase where data are sparse. The standard deviation of the new WPWP planktonic δ18O stack has an average value of 0.19 ‰ for the full stack and 0.17 ‰ for 0 to 450 ka, where data are more densely spaced.

Figure 3The WPWP planktonic δ18O stack mean (black) and 1 standard deviation (gray shading). Colored asterisks show the planktonic δ18O measurements from each core after applying the core-specific shift and scale parameters calculated during alignment. Data from MD97-2141 were smoothed and sampled at one-fifth the originally published resolution.

Table 2Core-specific shift and scale parameters and the standard deviation of δ18O residuals between the WPWP stack and each core (after applying the estimated shift and scale parameters).

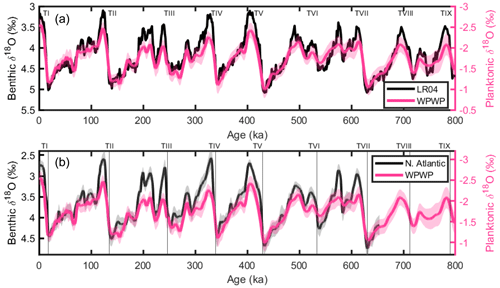

Figure 4Stack comparisons. (a) Comparison between our WPWP planktonic δ18O stack (pink) and the global LR04 benthic δ18O stack (black) (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005). (b) Comparison between our WPWP planktonic δ18O stack (pink) and a regional North Atlantic benthic δ18O stack (black) (Hobart et al., 2023). Shaded error bars represent 1 standard deviation in the WPWP and North Atlantic stacks. Glacial terminations are labeled with vertical lines based on ages for TI–TVII from Hobart et al. (2023) and TVIII–TIX from Lisiecki and Raymo (2005).

The WPWP planktonic stack (Fig. 4) has weaker glacial–interglacial amplitudes than the global LR04 benthic δ18O stack (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005) or a North Atlantic benthic δ18O stack produced by BIGMACS (Hobart et al., 2023). The average glacial–interglacial amplitude for Terminations I to V is 1.7±0.1 ‰ and 1.8±0.1 ‰ in the LR04 and North Atlantic benthic stacks, respectively, but only 1.2±0.1 ‰ in the WPWP planktonic stack. (The reported 1 standard deviation uncertainty for the mean amplitude of each stack is calculated using the time-dependent standard deviation of δ18O in each stack.) This amplitude difference is also reflected in the spectral analysis of the stacks. Across all three orbital frequencies, there is greater spectral power in the LR04 benthic stack than the WPWP planktonic stack (Fig. 5).

Figure 5Power spectral density of the WPWP planktonic δ18O stack (pink) and the LR04 benthic δ18O stack (black). Spectral power is calculated from 0 to 800 ka for both stacks using MATLAB's pmtm function (The MathWorks Inc., 2023). Orbital frequencies that correspond to 100, 41, 23, and 19 kyr are labeled with vertical dashed lines.

6.1 Age model assumptions

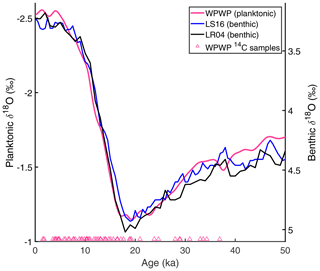

The use of the LR04 stack as an initial alignment target for our WPWP stack assumes that benthic and planktonic δ18O change synchronously; however, the signals recorded by benthic and planktonic δ18O could differ due to either a different transit time of the global ice volume signal to the deep ocean compared to surface of the WPWP and/or due to asynchronous temperature and salinity changes between the WPWP and high-latitude deep-water formation regions. To evaluate potential timing differences in the two signals, we compare the age model for the portion of the WPWP planktonic stack constrained by radiocarbon data (1.5 to 37 ka) to the equivalent portion of the LR04 and LS16 global benthic δ18O stacks (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Lisiecki and Stern, 2016). The LS16 global stack is constructed with direct 14C age constraints and is weighted towards the Pacific based on ocean basin volume, whereas the LR04 stack is based only on indirect age constraints and more heavily weighted toward Atlantic values (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Lisiecki and Stern, 2016). However, all three stacks show good agreement for the timing of δ18O change during Termination I, suggesting that age estimates for WPWP planktonic and benthic δ18O are similar on orbital timescales (Fig. 6). We also compare changes in planktonic and benthic δ18O measured within individual WPWP cores as a function of depth for MD05-2925, ODP-1143, and ODP-806 (Lo et al., 2019; Lo, 2021; Tian et al., 2006; Lea et al., 2000; Medina-Elizalde and Lea, 2005; Bickert et al., 1993). These cores do not show a consistent lead–lag between the planktonic δ18O and benthic δ18O records (Figs. S1–S3), additionally indicating that the timing of WPWP planktonic and benthic δ18O change is similar on orbital timescales.

The relative timing of millennial-scale variability between the WPWP planktonic stack and benthic δ18O is more difficult to evaluate. Apparent differences in timing of a millennial-scale feature in the stacks between 36 and 38 ka may be an artifact of age model uncertainty. Age uncertainty for the LR04 stack beyond 30 ka is ±4 kyr, and age estimates for the LS16 stack have a 95 % confidence interval width of 2 to 4 kyr between 30 and 40 ka. Age estimates for that portion of our WPWP stack are not well constrained due to the scarcity of radiocarbon data available beyond 30 ka. The portions of our WPWP stack older than 37 ka, which are not constrained by radiocarbon data, inherit the ±4 kyr age uncertainty of the LR04 stack used as the initial alignment target. Thus, we have no independent age estimates for WPWP planktonic δ18O change older than 37 ka.

Figure 6The WPWP planktonic δ18O stack (pink) compared to the global benthic δ18O stacks of Lisiecki and Stern (2016) (blue) and Lisiecki and Raymo (2005) (black). Triangles represent radiocarbon ages included in our WPWP stack construction (Oppo et al., 2003a; Lo et al., 2017; Regoli et al., 2015; Dang et al., 2020a; Zhang et al., 2021).

6.2 Application of BIGMACS to planktonic δ18O

6.2.1 Standard deviation of planktonic versus benthic stacks

The new Bayesian alignment software BIGMACS has previously only been applied to benthic δ18O data (Lee et al., 2023a), and this study is the first to use the software to stack planktonic δ18O data. To evaluate the performance of BIGMACS in stacking WPWP planktonic δ18O, we compare the average standard deviation of the new WPWP planktonic δ18O stack to two benthic δ18O stacks constructed with BIGMACS using six cores from the deep northeastern Atlantic (DNEA stack) and four cores from the intermediate tropical western Atlantic (ITWA stack). Based on the BIGMACS assumption of homogeneity across aligned records, all δ18O residuals are assumed to be internal errors associated with sampling noise and measurement uncertainty, and thus all residuals contribute similarly to estimating the stack's time-dependent standard deviation. A similar standard deviation for δ18O in the stacks would indicate a similar signal-to-noise ratio in the stacked data, suggesting similar effectiveness in the stacking process.

The DNEA and ITWA stacks have mean standard deviations of 0.13 ‰ and 0.2 ‰, respectively, for 0 to 60 ka (Lee et al., 2023a), while the new WPWP planktonic stack has a mean standard deviation of 0.16 ‰ for the same age range. A larger mean standard deviation of 0.19 ‰ for the full age range of 0 to 800 ka for our WPWP stack is likely due in part to the lower resolution of data used in the second half of the stack; however, it is still similar to the standard deviation of the ITWA benthic stack. The similar δ18O standard deviations for the planktonic and benthic stacks suggest that BIGMACS may be similarly effective at aligning and stacking homogeneous regional planktonic δ18O data as regional benthic δ18O data. However, before stacking either benthic or planktonic δ18O records, BIGMACS users should carefully evaluate whether the records to be aligned and stacked are homogeneous (i.e., share a common and synchronous signal).

6.2.2 Homogeneity of WPWP planktonic δ18O

The process of stack construction assumes that all included WPWP planktonic δ18O records have one homogeneous signal, i.e., that they all share the same underlying signal (with allowance for site-specific shift and scale values caused by physical processes, such as temperature and salinity gradients between the core locations). The shift and scale values calculated for each record during stack construction can be used as an estimate of how similar or different the means and amplitudes of the planktonic δ18O signals are between cores. The shift values of the 10 cores in the WPWP stack range between −0.62 ‰ and 0.64 ‰, and scale values range from 0.72 to 1.11 (Table 2). The benthic DNEA and ITWA stacks constructed using BIGMACS have a smaller range of shift and scale parameters than the WPWP stack. Shift values range from −0.07 ‰ to 0.25 ‰ and −0.25 ‰ to 0.3 ‰ for the DNEA and ITWA stacks, respectively; benthic scale values range between 0.92 and 1.04 for the DNEA stack and from 0.91 to 1 for the ITWA stack (Lee et al., 2023a). Thus, core-specific shift and scale values suggest more spatial variability in WPWP planktonic δ18O than in regional benthic δ18O compilations.

WPWP cores ODP-769A and MD97-2141, both of which are located in the Sulu Sea, have two of the largest negative shifts and smallest scale values (Linsley and von Breymann, 1991; Oppo et al., 2003b). Cores KX21-2, KX22-4, and ODP-806, located in the eastern open-ocean portion of the WPWP, also have small scale values and negative shifts (Dang et al., 2020b; Zhang et al., 2021; Lea et al., 2000; Medina-Elizalde and Lea, 2005). The similar shift and scale values for neighboring cores with different data resolution suggest that these results reflect real differences in SST or salinity variability within the WPWP and indicate a weaker amplitude for planktonic δ18O change at these sites. Previous studies show regional differences in δ18Oseawater that may explain the reduced amplitude of planktonic δ18O change at sites in the Sulu Sea and eastern WPWP (Lea et al., 2000; de Garidel-Thoron et al., 2005a). Unlike the central and southern WPWP where glacial surface water δ18O shifted toward more positive values at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (Visser et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2008; Li et al., 2016), sites ODP-769A, MD97-2141, KX21-2, KX22-4, and ODP-806 show negative shifts in surface water δ18O at the LGM (Rosenthal et al., 2003; Lea et al., 2000). The observed heterogeneity in δ18Oseawater likely results from regional differences in precipitation (de Garidel-Thoron et al., 2007) and/or the varied impacts of changes in sea level on the Indonesian throughflow and connectivity of regional seas (Linsley et al., 2010).

Although alignment of δ18O signals for stacking requires an assumption that the WPWP planktonic δ18O is homogenous, the BIGMACS estimated core-specific shift and scale parameters should still allow us to extract the underlying signal common to the region despite small differences in the mean and amplitude of the signal among core sites. The similar standard deviation for the planktonic stack compared to benthic stacks suggests that the shift and scale factors are effective for identifying a common, shared planktonic δ18O signal across the WPWP.

More variability in the planktonic δ18O data is expected because the surface ocean composition has greater spatial variability due to factors like temperature and salinity than the deep ocean, which could account for some of the disparity in shift and scale values of the benthic versus planktonic data. The greater spatial variability in planktonic data is one reason why regional planktonic stacks are more useful than global planktonic stacks. By describing regional patterns of response, regional planktonic stacks can improve age models based on stratigraphic alignment. The higher-resolution 0 to 450 ka portion of our WPWP stack may be particularly useful for this purpose. Although the new WPWP planktonic stack can improve estimates of relative age regionally, we caution that its absolute ages are susceptible to our assumption of synchronous change in benthic δ18O and WPWP planktonic δ18O as well as the absolute age uncertainty of the LR04 stack.

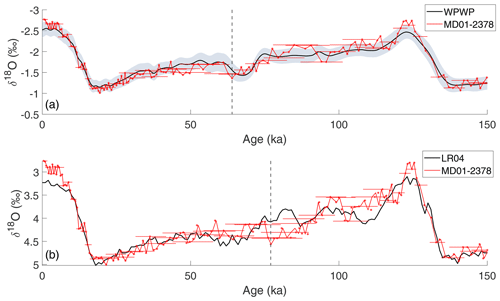

Figure 7MD01-2378 alignment target comparison. (a) Planktonic δ18O for core MD01-2378 (red, Holbourn et al., 2005b) aligned to the WPWP planktonic δ18O stack (black, with gray shading for 1 standard deviation in δ18O). (b) Planktonic δ18O for MD01-2378 (red, Holbourn et al., 2005b) aligned to the benthic δ18O LR04 stack (black, Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005). In both panels, red symbols mark MD01-2378 planktonic δ18O samples with shift and scale applied to match the respective alignment targets. Horizontal error bars indicate the 95 % CI alignment uncertainty for every third δ18O measurement (to improve figure legibility). The vertical dashed lines mark two different alignments of 8.81 m depth in MD01-2378, which shifts from 64 ka when aligned to the WPWP planktonic stack to 77 ka when aligned to the LR04 benthic stack.

6.2.3 Planktonic vs. benthic alignment uncertainty

Here we compare the age uncertainty during planktonic versus benthic alignment in BIGMACS. The average 95 % confidence interval width for alignment uncertainty across all WPWP cores is 4.8 kyr for the full length of the WPWP stack and 4.4 kyr for the 0 to 450 ka portion of the stack, which has higher-resolution data. Similarly, a North Atlantic benthic δ18O stack also constructed using BIGMACS has an average alignment uncertainty of 4.4 kyr for the 0 to 654 ka length of that stack (Hobart et al., 2023). Thus, despite differences in the amplitude and spatial variability of WPWP planktonic δ18O compared to North Atlantic benthic δ18O, alignment uncertainty is similar for the construction of planktonic and benthic δ18O stacks. During most of the stack construction process, all records used for alignment are exclusively planktonic or benthic δ18O. (Although the LR04 benthic stack is used as the initial alignment target for the WPWP stack, the BIGMACS alignment target is updated to reflect the mean planktonic δ18O signal during each iteration of stack construction.)

BIGMACS assumes that the records used for alignment share the same underlying signals; therefore, alignment should be more reliable with smaller uncertainties when a nearby planktonic δ18O record is aligned to the WPWP planktonic stack rather than the LR04 benthic stack. We demonstrate the potential impacts of aligning to different stacks by comparing the age estimates for the planktonic δ18O record of core MD01-2378 (Holbourn et al., 2005a) from the Timor Sea (slightly outside the boundaries of the WPWP) based on alignment to either the WPWP stack or the LR04 stack (Bowman et al., 2023). Differences between the features of the two stacks during MIS 3 and 4 produce a ∼14 kyr error in the alignment of the core to the LR04 stack, as indicated by the shifted position of the dashed vertical line in Fig. 7. The proper alignment of MIS 4 to the WPWP stack produces a 95 % CI width of 6.5 kyr for estimated age at that time compared to a 95 % CI width of 13 to 18 kyr associated with the incorrect alignment to the LR04 stack. Because the planktonic δ18O records near the WPWP share features which differ from those of benthic δ18O, age model results for WPWP cores should be more accurate when their planktonic δ18O records are aligned to the WPWP stack than to a benthic stack.

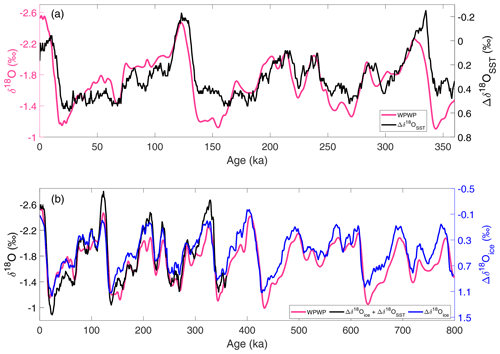

Figure 8Ice volume and temperature contributions to WPWP planktonic δ18O. (a) The WPWP planktonic δ18O stack (pink) and the IPWP SST stack of Jian et al. (2022), on its original age model and converted to Δ δ18O per mil equivalent (black). (b) The WPWP stack (pink) compared to a sea level stack (Spratt and Lisiecki, 2016) converted to Δδ18Oice per mil equivalent (blue) and the sum of Δδ18OSST and Δδ18Oice change (black).

Figure 9Normalized power spectral density of the WPWP planktonic δ18O stack (pink) and IPWP SST stack (black, Jian et al., 2022) from 0 to 360 ka for both stacks using MATLAB's pmtm function (The MathWorks Inc., 2023). Orbital frequencies that correspond to 100, 41, 23, and 19 kyr are marked by vertical dashed lines.

6.3 Contributions of SST and ice volume to WPWP planktonic δ18O

A recent study by Jian et al. (2022) constructed an IPWP SST stack from 0 to 360 ka. We compare the orbital-scale variability between the SST stack and our planktonic δ18O stack using spectral analysis and by converting the SST stack change to Δδ18OSST, which is an estimate of the oxygen isotope fractionation in foraminiferal carbonate caused by SST. Many of the same features can be seen in the WPWP stacks of planktonic δ18O and SST (Fig. 8, top); however, the planktonic δ18O values of the last two interglacials are similar to one another, whereas Holocene SST is notably cooler than the SST of the penultimate interglacial. The WPWP planktonic δ18O and SST stacks have similar proportions of normalized spectral power at orbital frequencies, but SST has slightly less obliquity power and slightly more precession power (Fig. 9).

To estimate the combined effects of SST and ice volume change, the IPWP Δδ18OSST was added to an estimate of Δδ18Oice (Fig. 8, bottom) from a global sea level (ice volume) stack (Spratt and Lisiecki, 2016). The combined SST and ice volume Δδ18OSST+ice should represent the majority of the planktonic δ18O change in our WPWP planktonic δ18O stack, except for salinity-induced changes. The two combined Δδ18O components show similar glacial–interglacial cyclicity and timing of change as our WPWP planktonic δ18O stack but with a slightly larger amplitude, particularly during MIS 2 and 3 (20 to 70 ka), MIS 7 (200 to 250 ka), and MIS 9 (310 to 330 ka). Salinity-induced changes in the δ18O of WPWP surface water may offset some of the WPWP Δδ18OSST+ice signal. However, some of the discrepancy could also be explained by spatial variability in the IPWP if the sites used for our WPWP planktonic δ18O stack had less average SST change than those in the IPWP SST stack (Jian et al., 2022).

The WPWP planktonic δ18O stack be accessed on Zenodo with the DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10211900 (Bowman et al., 2023) in the “WPWP_planktonic_stack.txt” file, which contains the age, mean δ18O, and δ18O standard deviation. The same file is also available as “stack.txt” in the WPWP_10cores_v12_stack_output.zip file. The previously published depth and planktonic δ18O data as well as any radiocarbon or tie points for each core used during stack construction can be found as .txt files in the “Inputs” folder. BIGMACS-produced age models, depth, calibrated radiocarbon ages, and planktonic δ18O data for each core can be found in the “Outputs” folder in the “results.mat” file and as .txt files in the individual folders named for each core.

The planktonic δ18O alignments for core MD01-2378 (Holbourn et al., 2005b; https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.263757) to both the WPWP planktonic δ18O stack and the LR04 benthic δ18O stack (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005) can also be accessed via the DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10211900 (Bowman et al., 2023). The BIGMACS-produced age model and the data used for the alignment can be found in the “results.mat” file of the “MD01-2378_WPWPalignment_output.zip” (or “… LR04alignment_output”) files. The age model results can also be found in text file form in the “Ages” folder of the output folders. The depth, radiocarbon, and planktonic δ18O data used for alignments can be found in text file form in the “MD01-2378” folder of the “MD01-2378_WPWPalignment_input.zip” (or “… LR04alignment_input”) files.

The alignment software BIGMACS (Lee et al., 2023b) used to construct our WPWP stack can be downloaded at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8327654.

We present a regional planktonic δ18O stack of the Western Pacific Warm Pool constructed from 10 previously published cores using the new alignment software BIGMACS (Lee et al., 2023b). The stack age model is constrained by 65 radiocarbon dates from 1.5 to 37 ka in four WPWP cores and otherwise follows the age model of the LR04 benthic δ18O stack (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005). Within the radiocarbon time interval, the timing of WPWP planktonic δ18O appears to be nearly synchronous with global mean benthic δ18O change. The WPWP planktonic δ18O stack provides a useful regional alignment target for WPWP planktonic δ18O records, particularly for the 0 to 450 ka portion, which has a higher resolution than the older portion of the stack. Future improvements to the WPWP stack could include higher-resolution planktonic δ18O in the older portion of the stack and better age constraints beyond 37 ka.

Analyses of the stack's standard deviation and alignment uncertainty suggest that BIGMACS performs similarly well stacking WPWP planktonic δ18O as it does for regional benthic δ18O data. The new stack has weaker glacial–interglacial amplitudes and orbital power for WPWP planktonic δ18O change than benthic δ18O stacks over the last 800 kyr. WPWP planktonic δ18O change is also somewhat weaker than estimated based on global ice volume and IPWP SST change, perhaps due to spatial heterogeneity or surface salinity change. Differences in glacial–interglacial amplitudes between the WPWP planktonic stack and benthic δ18O stacks validate the fact that these differences are characteristic of planktonic δ18O throughout the WPWP. Furthermore, stratigraphic alignments of planktonic δ18O from cores near the WPWP should produce more reliable relative age estimates when aligned to the WPWP planktonic stack instead of a benthic δ18O stack.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-701-2024-supplement.

CLB curated the previously published data, performed the formal analysis, constructed the visualization, and prepared the original draft. DSR was involved with age model methodology and software development, visualization, and paper review and editing. LEL conceptualized the project, supervised the project, and contributed to the original draft preparation and paper review and editing. SCB provided validation and paper review and editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We thank Manfred Mudelsee and three anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) (project number OCE-1760878).

This paper was edited by Attila Demény and reviewed by Manfred Mudelsee and three anonymous referees.

Bemis, B. E., Spero, H. J., Bijma, J., and Lea, D. W.: Reevaluation of the oxygen isotopic composition of planktonic foraminifera: Experimental results and revised paleotemperature equations, Paleoceanogr., 13, 150–160, https://doi.org/10.1029/98PA00070, 1998.

Bickert, T., Berger, W. H., Burke, S., Schmidt, H., and Wefer, G.: (Appendix A) Stable oxygen and carbon isotope ratios of Cibicidoides wuellerstorfi from ODP Hole 130-806B on the Ontong Java Plateau, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.696408 (last access: 27 November 2023), 1993.

Bowman, C. L., Rand, D. S., Lisiecki, L. E., and Bova, S. C.: An 800 kyr planktonic δ18O stack for the West Pacific Warm Pool, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10211900 (last access: 27 November 2023), 2023.

Broccoli, A. J.: Tropical Cooling at the Last Glacial Maximum: An atmosphere–mixed layer ocean model simulation, J. Climate, 13, 951–976, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2000)013<0951:TCATLG>2.0.CO;2, 2000.

Chuang, C., Lo, L., Zeeden, C., Chou, Y., Wei, K., Shen, C., Mii, H., Chang, Y., and Tung, Y.: Integrated stratigraphy of ODP Site 1115 (Solomon Sea, southwestern equatorial Pacific) over the past 3.2 Ma, Mar. Micropaleonto., 144, 25–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2018.09.003, 2018.

Chuang, C., Lo, L., Zeeden, C., Chou, Y., Wei, K., Shen, C., Mii, H., Chang, Y., and Tung, Y.: Isotopic analysis of Globigerinoides sacculifer from ODP Hole 180-1115B, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.899187 (last access: 3 May 2023), 2019.

Dang, H., Wu, J., Xiong, Z., Qiao, P., Li, T., and Jian, Z.: Orbital and sea-level changes regulate the iron-associated sediment supplies from Papua New Guinea to the equatorial Pacific, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 239, 106361, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106361, 2020a.

Dang, H., Wu, J., Xiong, Z., Qiao, P., Li, T., and Jian, Z.: Oxygen isotopes of Globigerinoides ruber from core KX21-2 from the western equatorial Pacific over the last ∼400 ka, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.922658 (last access: 7 November 2023), 2020b.

De Deckker, P.: The Indo-Pacific Warm Pool: critical to world oceanography and world climate, Geosci. Lett., 3, 20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40562-016-0054-3, 2016.

de Garidel-Thoron, T., Rosenthal, Y., Bassinot, F., and Beaufort, L.: Stable sea surface temperatures in the Western Pacific Warm Pool over the past 1.75 million years, Nature, 433, 294–298, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03189, 2005a.

de Garidel-Thoron, T., Rosenthal, Y., Bassinot, F. C., and Beaufort, L.: Western Pacific Warm Pool Pleistocene paired δ18O-Mg/Ca and SST reconstruction, NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information [data set], https://doi.org/10.25921/ejer-t729 (last access: 3 May 2023), 2005b.

de Garidel-Thoron, T., Rosenthal, Y., Beaufort, L., Bard, E., Sonzogni, C., and Mix, A. C.: A multiproxy assessment of the western equatorial Pacific hydrography during the last 30 Kyr, Paleoceanogr., 22, PA3204, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006PA001269, 2007.

Heaton, T. J., Köhler, P., Butzin, M., Bard, E., Reimer, R. W., Austin, W. E. N., Ramsey, C. B., Grootes, P. M., Hughen, K. A., Kromer, B., Reimer, P. J., Adkins, J., Burke, A., Cook, M. S., Olsen, J., and Skinner, L. C.: Marine20 – The marine radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55,000 Cal BP), Radiocarbon, 62, 779–820, https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2020.68, 2020.

Hobart, B., Lisiecki, L. E., Rand, D., Lee, T., and Lawrence, C. E.: Late Pleistocene 100-kyr glacial cycles paced by precession forcing of summer insolation, Nat. Geosci., 16, 717–722, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01235-x, 2023.

Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Kawamura, H., Jian, Z., Grootes, P., Erlenkeuser, H., and Xu, J.: Orbitally paced paleoproductivity variations in the Timor Sea and Indonesian Throughflow variability during the last 460 Kyr, Paleoceanogr., 20, PA3002, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004PA001094, 2005a.

Holbourn, A. E., Kuhnt, W., Kawamura, H., Jian, Z., Grootes, P. M., Erlenkeuser, H., and Xu, J.: Stable isotopes on planktic foraminifera of sediment core MD01-2378, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.263757 (last access: 11 October 2023), 2005b.

Hollstein, M., Mohtadi, M., Rosenthal, Y., Moffa Sanchez, P., Oppo, D., Martínez Méndez, G., Steinke, S., and Hebbeln, D.: Stable oxygen isotopes and Mg/Ca in planktic foraminifera from modern surface sediments of the Western Pacific Warm Pool: Implications for thermocline reconstructions, Paleoceanogr., 32, 1174–1194, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017PA003122, 2017.

Huybers, P. and Wunsch, C.: A depth-derived Pleistocene age model: Uncertainty estimates, sedimentation variability, and nonlinear climate change, Paleoceanogr., 19, PA1028, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002PA000857, 2004.

Imbrie, J., Hays, J. D., Martinson, D. G., McIntyre A., Mix A. C., Morley, J. J., Pisias N. G., Prell, W. L., and Shackleton, N. J.: The orbital theory of Pleistocene climate: Support from a revised chronology of the marine δ18O record, Milankovitch and Climate, Part 1, edited by: Berger, A., Imbrie, J., Kukla, G., Saltzman, B., and Reidel, D., Publishing Company, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 269–305, ISBN 9027717915, 1984.

Jian, Z., Wang, Y., Dang, H., Mohtadi, M., Rosenthal, Y., Lea, D. W., Liu, Z., Jin, H., Ye, L., Kuhnt, W., and Wang, X.: Warm Pool ocean heat content regulates ocean–continent moisture transport, Nature, 612, 92–99, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05302-y, 2022.

Lea, D. W.: The 100,000-Yr Cycle in tropical SST, greenhouse forcing, and climate sensitivity, J. Climate, 17, 2170–2179, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<2170:TYCITS>2.0.CO;2, 2004.

Lea, D. W., Pak, D. K., and Spero, H. J.: Climate impact of Late Quaternary equatorial Pacific sea surface temperature variations, Science, 289, 1719–1724, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5485.1719, 2000.

Lee, T., Rand, D., Lisiecki, L. E., Gebbie, G., and Lawrence, C.: Bayesian age models and stacks: combining age inferences from radiocarbon and benthic δ18O stratigraphic alignment, Clim. Past, 19, 1993–2012, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-19-1993-2023, 2023a.

Lee, T., Rand, D., Lisiecki, L. E., Gebbie, G., and Lawrence, C.: BIGMACS, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8327654 (last access: 27 November 2023), 2023b.

Li, L., Li, Q., Tian, J., Wang, P., Wang, H., and Liu, Z.: A 4-Ma record of thermal evolution in the tropical western Pacific and its implications on climate change, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 309, 10–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.04.016, 2011.

Li, Z.; Shi, X., Chen, M.-T., Wang, H., Liu, S., Xu, J., Long, H., Troa, R. A., Zuraida, R., and Triarso, E.: Late Quaternary fingerprints of precession and sea level variation over the past 35 Kyr as revealed by sea surface temperature and upwelling records from the Indian Ocean near southernmost Sumatra, Quaternary Int., 425, 282–291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2016.07.013, 2016.

Linsley, B. K. and von Breymann, M. T.: Stable isotopic and geochemical record in the Sulu Sea during the last 750 k.y.: Assessment of surface water variability and paleoproductivity changes, Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, 24, 379–396, https://doi.org/10.2973/odp.proc.sr.124.151.1991, 1991.

Linsley, B., Rosenthal, Y., and Oppo, D.: Holocene evolution of the Indonesian Throughflow and the Western Pacific Warm Pool, Nat. Geosci., 3, 578–583, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo920, 2010.

Lisiecki, L. E. and Raymo, M. E.: A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records, Paleoceanogr., 20, PA1003, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004PA001071, 2005.

Lisiecki, L. E. and Stern, J. V.: Regional and global benthic δ18O stacks for the last glacial cycle, Paleoceanogr., 31, 1368–1394, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016PA003002, 2016.

Lo, L.: A dataset of the Mid-Brunhes period at site MD05-2925, Solomon Sea: Surface-subsurface planktonic foraminifera stable oxygen isotope and Mg/Ca ratios, Mendeley Data [data set], https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/9c2nnpchdh/1 (last access: 14 October 2023), 2021.

Lo, L., Chang, S., Wei, K., Lee, S., Ou, T., Chen, Y., Chuang, C., Mii, H., Burr, G. S., Chen, M., Tung, Y., Tsai, M., Hodell, D. A., and Shen, C.: Nonlinear climatic sensitivity to greenhouse gases over past 4 glacial/interglacial cycles, Sci. Rep.-UK, 7, 4626, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04031-x, 2017.

Lo, L., Chang, S., Wei, K., Lee, S., Ou, T., Chen, Y., Chuang, C., Mii, H., Burr, G. S., Chen, M., Tung, Y., Tsai, M., Hodell, D. A., and Shen, C.: Age model and oxygen isotopes of planktonic foraminifera from sediment core MD05-2925 off the Solomon Sea, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.899216 (last access: 14 October 2023), 2019.

Locarnini, R. A., Mishonov, A. V., Baranova, O. K., Boyer, T. P., Zweng, M. M., Garcia, H. E., Reagan, J. R., Seidov, D., K. Weathers, Paver, C. R., and Smolyar, I.: Temperature, world ocean atlas 2018, NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81 [data set], https://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00651/76338/ (last access: 7 November 2023), 2018.

Mayer, M., Haimberger L., and Balmaseda, M. A.: On the energy exchange between tropical ocean basins related to ENSO, J. Climate, 27, 6393–6403, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00123.1, 2014.

Medina-Elizalde, M. and Lea, D. W.: (Table S2) Stable oxygen isotope record and Mg/Ca ratios of Globigerinoides ruber from ODP Hole 130-806B, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.772014 (last access: 4 October 2023), 2005.

Neale, R. and Slingo J.: The Maritime Continent and its role in the global climate: A GCM study, J. Climate, 16, 834–848, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016<0834:TMCAIR>2.0.CO;2, 2003.

Oppo, D. W., Linsley, B. K., Rosenthal, Y., Dannenmann, S., and Beaufort, L.: Orbital and suborbital climate variability in the Sulu Sea, western tropical Pacific, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 4, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GC000260, 2003a.

Oppo, D. W., Linsley, B. K., Rosenthal, Y., Dannenmann, S., and Beaufort, L.: Sulu Sea core MD97-2141 foraminiferal oxygen isotope data, NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information [data set], https://doi.org/10.25921/qqqx-kt90 (last access: 11 October 2023), 2003b.

Past Interglacials Working Group of PAGES: Interglacials of the last 800,000 years, Rev. Geophys., 54, 162–219, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015RG000482, 2016.

Regoli, F., de Garidel-Thoron, T., Tachikawa, K., Jian, Z., Ye, L., Droxler, A. W., Lenoir, G., Crucifix, M., Barbarin, N., and Beaufort, L.: Progressive shoaling of the equatorial Pacific thermocline over the last eight glacial periods, Paleoceanogr., 30, 439–455, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014PA002696, 2015.

Rosenthal, Y., Oppo, D. W., and Linsley, B. K.: The amplitude and phasing of climate change during the last deglaciation in the Sulu Sea, western equatorial Pacific, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 1428, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL016612, 2003.

Sadekov, A., Eggins, S. M., De Deckker, P., Ninnemann, U., Kuhnt, W., and Bassinot, F.: Surface and subsurface seawater temperature reconstruction using Mg/Ca microanalysis of planktonic foraminifera Globigerinoides ruber, Globigerinoides sacculifer, and Pulleniatina obliquiloculata, Paleoceanogr., 24, PA3201, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008PA001664, 2009.

Shakun, J. D., Lea, D. W., Lisiecki, L. E., and Raymo, M. E.: An 800-Kyr record of global surface ocean δ18O and implications for ice volume-temperature coupling, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 426, 58–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.05.042, 2015.

Spero, H. J., Mielke, K. M., Kalve, E. M., Lea, D. W., and Pak, D. K.: Multispecies approach to reconstructing eastern equatorial Pacific thermocline hydrography during the past 360 Kyr, Paleoceanogr., 18, 1022, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002PA000814, 2003.

Spratt, R. M. and Lisiecki, L. E.: A Late Pleistocene sea level stack, Clim. Past, 12, 1079–1092, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-12-1079-2016, 2016.

Tachikawa, K., Timmermann, A., Vidal, L., Sonzogni, C., and Timm, O. E.: CO2 radiative forcing and Intertropical Convergence Zone influences on Western Pacific Warm Pool climate over the past 400 ka, Quaternay Sci. Rev., 86, 24–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.12.018, 2014.

The MathWorks Inc.: MATLAB version: 9.14.0 (R2023a), Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc., https://www.mathworks.com (last access: 30 November 2023), 2023.

Tian, J. Pak, Dorothy K., Wang, P., Lea, D. W., Cheng, X., and Zhao, Q.: (Appendix 1) Stable oxygen isotope ratios of Globigerinoides ruber and benthic foraminifera from ODP Site 184-1143, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.707833 (last access: 14 October 2023), 2006.

Visser, K., Thunell, R., and Stott, L.: Magnitude and timing of temperature change in the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool during deglaciation, Nature, 421, 152–155, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01297, 2003.

Wefer, G. and Berger, W. H.: Isotope paleontology: Growth and composition of extant calcareous species, Mar. Geol., 100, 207–248, https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(91)90234-U, 1991

Xu, J., Holbourn, A., Kuhnt, W., Jian, Z., and Kawamura, H.: Changes in the thermocline structure of the Indonesian Outflow during terminations I and II, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 273, 152–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.06.029, 2008.

Zhang, S., Yu, Z., Gong, X., Wang, Y., Chang, F., and Li, T.: Sable oxygen isotope and Mg/Ca ratios of planktonic foraminifera from KX97322-4 (KX22-4), PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.939377 (last access: 11 October 2023), 2021.