the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Multi-year observations of BVOCs and ozone: concentrations and fluxes measured above and below the canopy in a mixed temperate forest

Bert Willem Diane Verreyken

Niels Schoon

Benjamin Bergmans

Bernard Heinesch

Crist Amelynck

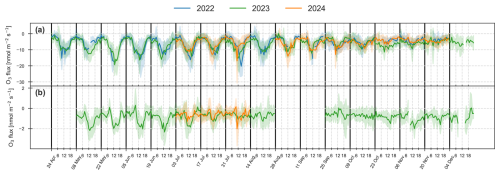

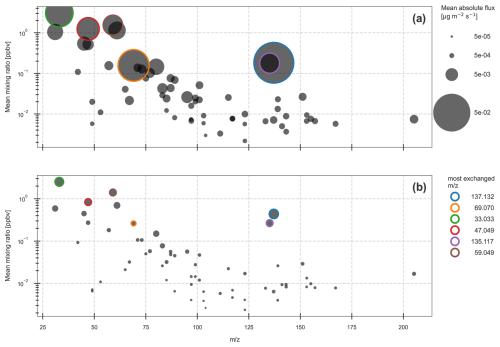

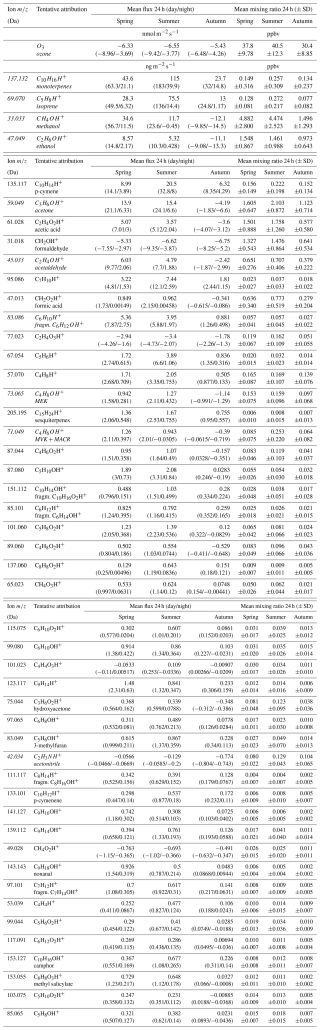

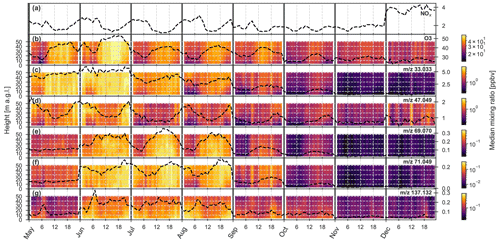

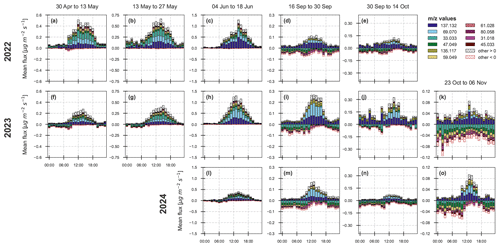

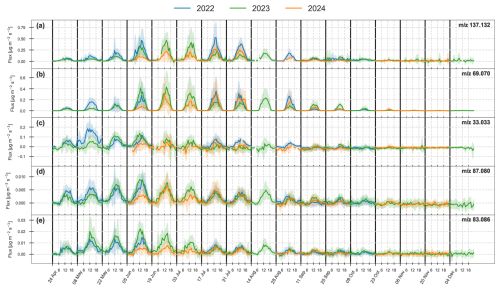

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and ozone (O3) are key constituents of tropospheric chemistry, affecting both air quality and climate. Forests are major emitters of biogenic VOCs (BVOCs), yet large uncertainties remain regarding the diversity of exchanged compounds, the drivers of their bidirectional fluxes, and their in-canopy chemistry. Long-term and comprehensive in situ datasets remain scarce, limiting our understanding of these complex processes. We conducted a 3-year field campaign (2022–2024) at the Integrated Carbon Observation System mixed temperate forest station of Vielsalm (BE-Vie), combining vertical concentration profile and eddy covariance flux measurements above and below the canopy (concentration dataset: https://doi.org/10.18758/NVFBA74V, Verreyken et al., 2025c; flux dataset: https://doi.org/10.18758/KHV8ZXU2, Dumont et al., 2025a; concentration-turbulence profile dataset: https://doi.org/10.18758/BED4Q2VY, Dumont et al., 2025b). Using a PTR-ToF-MS and an open-source data-processing workflow, we identified 48 significantly exchanged VOCs. The vertical and diurnal gradients of the mixing ratios reflected the interplay between emission, deposition, chemistry, and transport. Combined with a profile of turbulence statistics, these observations offer an opportunity to investigate their behaviour within the canopy. The forest acted as a net VOC source in summer (∼ 1.25 µg m−2 s−1), while deposition dominated in autumn. Many oxygenated VOCs displayed bidirectional exchange. Monoterpenes, isoprene, and methanol were the most abundant flux contributors, but 15–30 (30–43) compounds were needed to account for 90 % of total emissions (depositions), depending on the season. Below-canopy BVOC and O3 fluxes reached ∼ 10 % of above-canopy ones, with proportionally enhanced below-canopy ozone uptake at night. This study provides one of the most detailed long-term datasets of VOC and O3 exchange in a temperate forest and serves as a key reference for improving process-based models of biogenic, physical, and chemical exchange in forest ecosystems.

- Article

(9462 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1784 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) form a heterogeneous group of reactive trace gases that play a key role in atmospheric chemistry. Together with nitrogen oxides (NOx), they contribute to both the formation and destruction of tropospheric ozone (Stockwell and Forkel, 2002), influencing regional ozone pollution. By reacting with hydroxyl and peroxy radicals, VOCs also affect the atmospheric oxidizing capacity and the lifetime of methane (Yoon et al., 2025), the second most important radiatively active gas after carbon dioxide (Canadell et al., 2021). In addition, VOCs are precursors in the formation and growth of secondary organic aerosols (SOA) (Mahilang et al., 2021), thereby degrading air quality, impacting human health, and influencing climate through interactions with radiation and serving as cloud condensation nuclei.

Each year, terrestrial ecosystems emit over 1000 Tg of organic carbon in the form of biogenic VOCs (BVOCs), excluding methane (Guenther et al., 2012). This exceeds global emissions of methane (∼ 550 Tg yr−1) (Saunois et al., 2016) and anthropogenic VOCs (∼ 200 Tg yr−1) (Huang et al., 2017). Forests are the dominant BVOC emitters among terrestrial ecosystems (Isidorov et al., 2022, and references therein), making them a longstanding focus of atmospheric research. Within forests, Guenther et al. (2012) estimated that broadleaf deciduous temperate trees rank third in isoprene emissions, contributing 35.4 Tg yr−1, compared to 244 and 178 Tg yr−1 for tropical evergreen and deciduous forests, respectively. Similarly, needleleaf evergreen temperate trees are the third largest monoterpene emitters, with 7.38 Tg yr−1, behind tropical evergreen and deciduous forests (82.9 and 45 Tg yr−1, respectively). These estimates suggest that temperate forests composed of mixed deciduous and needleleaf species deserve particular attention.

Ozone (O3), in addition to its role in radiative forcing as a potent greenhouse gas (Rowlinson et al., 2020), is toxic to both humans and plants. In terrestrial ecosystems, it undergoes various dry deposition pathways – including stomatal and non-stomatal processes such as uptake by leaf cuticles, soil, snow, or water surfaces (Clifton et al., 2020). Ozone deposition contributes significantly to reducing tropospheric ozone levels. However, when ozone enters leaves through stomata, it generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage plant cells, accelerate senescence, and reduce carbon assimilation via photosynthesis (Fiscus et al., 2005).

Despite decades of research into ozone uptake partitioning (Padro, 1996; Cieslik, 1998; Lamaud et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002; Mikkelsen et al., 2004; Fares et al., 2014; Horváth et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017b; Finco et al., 2018; Gerosa et al., 2022b), significant uncertainties remain. One such uncertainty lies in the reactions of ozone with BVOCs, which constitute an increasingly recognized atmospheric sink (Clifton et al., 2020, and references therein). This process, however, remains highly variable and difficult to quantify (Kurpius and Goldstein, 2003; Goldstein et al., 2004; Wolfe et al., 2011; Vermeuel et al., 2021).

Unlike ozone, BVOCs can undergo both emission and deposition. Early research primarily focused on isoprene and monoterpenes – the two most widely emitted isoprenoids globally (Guenther et al., 2012) – whose fluxes were long considered exclusively upward, with isoprene emissions driven by light and temperature and monoterpene emissions by temperature alone (Guenther et al., 1995). Later studies extended global emission inventories to include oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs, e.g., methanol, ethanol, acetone, acetaldehyde, formaldehyde, formic and acetic acids), sesquiterpenes, and isoprenoid oxidation products (Niinemets et al., 2014; Guenther et al., 2012), but largely continued to focus on emissions rather than deposition. Yet, in situ studies have highlighted non-negligible deposition fluxes of BVOCs (Karl et al., 2010; Bamberger et al., 2011; Jardine et al., 2011; Ruuskanen et al., 2011; Laffineur et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013a; Nguyen et al., 2015; Wohlfahrt et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2017b), which are now recognized as significant in global budgets. For instance, Safieddine et al. (2017) estimated that 460 Tg C yr−1 of reactive organic carbon is removed from the atmosphere via physical deposition. A regional simulation over the U.S. further showed that dry and wet deposition of organic vapours accounted for 60 %–75 % of the removal of tropospheric SOA burden in summer 2010 by limiting the availability of SOA precursors (Hodzic et al., 2014).

It is now well established that many BVOCs undergo bidirectional exchange. Yet, emissions and depositions are generally modelled separately in chemical transport models (CTMs), despite being driven by similar environmental variables (Forkel et al., 2015). Emissions are often simulated using the MEGAN model (for example, Sindelarova et al., 2014; Opacka et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2023), one of the most widely used biogenic emission models, which combines species-specific emission potentials with responses to light, temperature, CO2 inhibition, and leaf age (Guenther et al., 2012). Deposition, in contrast, is usually calculated as the product of ambient concentration and deposition velocity, using an Ohm’s law analogy introduced by Wesely (1989). This approach depends on deposition velocity estimates, which are still scarce, uncertain, and rarely incorporate seasonal variation (Niinemets et al., 2014). Other frameworks based on compensation points require precise knowledge of intercellular VOC concentrations and stomatal behaviour, and are difficult to upscale to the ecosystem level (Niinemets et al., 2014).

An additional process often overlooked in surface exchange models is in-canopy chemistry, which, in interaction with turbulent mixing, can significantly alter fluxes of highly reactive compounds such as sesquiterpenes (Forkel et al., 2015). VOCs can be lost between their point of release and the atmosphere above the canopy, where chemical processing depends strongly on turbulent mixing and residence times within the canopy (Rinne et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2017b), affecting CTM predictions of atmospheric concentrations in ways that are not yet adequately represented (Vermeuel et al., 2024; Link et al., 2024). Accounting for these reactions also requires identifying the vertical distribution of sources and sinks within the canopy. Although several studies have applied inverse modelling to approach this question, few ecosystems and tracers have been characterized to date (Karl et al., 2004a; Tiwary et al., 2007; Wada et al., 2020; Petersen et al., 2023). Overall, there is a growing call for a unified framework to model bidirectional BVOC exchange, integrating altogether dry and wet deposition, direct emissions, and in-canopy chemistry (Pleim and Ran, 2011; Niinemets et al., 2014; Forkel et al., 2015).

While emission models such as MEGAN have become increasingly sophisticated, they still represent only a fraction of the chemical diversity of atmospheric VOCs. For example, MEGAN2.1 includes 147 compounds (Guenther et al., 2012), whereas most CTMs simulate only 30–45 species (Millet et al., 2018). This limited representation contrasts starkly with field observations: Goldstein and Galbally (2007) estimated that between 104 and 105 distinct organic compounds have been detected in the atmosphere. Flux measurements have also revealed remarkable chemical diversity, with over 500 VOC-related ions observed over an orange orchard (Park et al., 2013a) and 377 over a temperate forest (Millet et al., 2018).

Improving VOC exchange parametrizations requires in situ, ecosystem-scale flux measurements across a diversity of ecosystems and environmental conditions. Traditionally, such measurements relied on disjunct eddy covariance (Muller et al., 2010; Laffineur et al., 2011, 2012, 2013; Rinne et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2013; Seco et al., 2015; Bachy et al., 2016, 2018; Seco et al., 2017) and, more occasionally, on surface-layer gradient and profile methods (Rantala et al., 2014, and references therein), using PTR-Quad-MS instruments. Using this type of instrument allowed the monitoring of a limited number of pre-selected compounds and could not resolve isobaric interferences. As a consequence, this technique was mostly used to investigate well-known BVOCs (Schallhart et al., 2016). More recently, the advent of PTR-ToF-MS coupled with eddy covariance enabled the simultaneous detection of fluxes for hundreds of VOCs with improved sensitivity and mass resolution, allowing isobar separation (Ruuskanen et al., 2011; Kaser et al., 2013; Park et al., 2013a, b; Brilli et al., 2014, 2016; Schallhart et al., 2016; Juráň et al., 2017; Millet et al., 2018; Schallhart et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2018; Fischer et al., 2021; Manco et al., 2021; Loubet et al., 2022; Petersen et al., 2023; Vermeuel et al., 2023b). However, many studies remained compound-targeted, and the technical complexity of PTR-ToF-MS operation and data processing limited their temporal coverage (Rinne et al., 2016). As a result, long-term flux measurements across seasons and under variable conditions remain scarce.

In this study, we revisit a temperate mixed forest in southern Belgium (Vielsalm station, BE-Vie), more than 10 years after the first PTR-Quad-MS flux measurements (Laffineur et al., 2011, 2012, 2013), with the aim of expanding the existing dataset. Using a PTR-ToF-MS and ozone analysers, we conducted a 3-year measurement campaign to obtain:

- i.

1 min concentrations of BVOCs and O3 above the canopy and at ground level,

- ii.

30 min fluxes of BVOCs and O3 above the canopy and at ground level,

- iii.

vertical profiles of BVOC and O3 concentrations at seven levels from the trunk space to above the canopy, and

- iv.

vertical profiles of turbulence measured by sonic anemometers at eight levels.

We provide a detailed description of the VOC data processing workflow – including newly developed and openly available processing tools – from raw PTR-ToF-MS signal treatment to compound identification, quantification, flux calculation, and data flagging, following a non-targeted and comprehensive approach. Ozone flux data processing is also described in detail, and methodological issues raised in earlier studies (Muller et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2015) are discussed.

To our knowledge, this study presents the longest combined VOC and ozone flux dataset publicly available to date, spanning 3 years and covering seasonal transitions from spring to summer and summer to autumn. Combined with additional open-access measurements at the site (extensive meteorological and phenological characterization, BTEX, HAPs, NOx, fine particles, and aerosols), this structured database offers a unique opportunity to address key knowledge gaps. These include quantifying the magnitude and diversity of BVOC exchange in temperate forests, their influence on ozone levels, the dynamics of bidirectional fluxes, the spatial distribution of sources and sinks, and the role of in-canopy chemistry. As a result, it provides a strong basis for improving current parametrizations in surface exchange models and CTMs, and to advancing our understanding of VOC and ozone interactions in the Earth system.

2.1 Study site

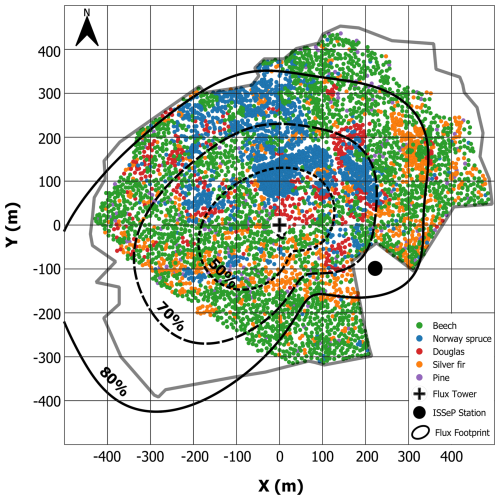

The study site (BE-Vie) is a mature mixed forest ecosystem, located in Vielsalm in the Belgian Ardenne region (50°18′ N, 6°00′ E; altitude 470 m a.s.l.). This site is part of several gas measurement networks: ICOS (class 2 ecosystem station) (https://www.icos-cp.eu/, last access: 13 January 2026), ACTRIS (for particle and gas in situ) (https://www.actris.eu/, last access: 13 January 2026), and EMEP (level 1 station) (https://www.emep.int/, last access: 13 January 2026). Its climate is temperate maritime and the 50-100 cm deep soil is classified as a dystric cambisol. The vegetation within the target area (that is, the area that contributes the most to fluxes measured at the flux tower) is a mixture of coniferous species, mainly Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst., mean height 17 m), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mirb.] Franco, 37 m) and Silver fir (Abies alba Miller, 26 m); and deciduous species, mainly European beech (Fagus sylvatica L., 22 m). Tree heights are reported from the last extensive inventory in the surroundings of the flux tower (2019), yielding an overall mean tree height of 26 m. Besides tree saplings, the understory vegetation is very sparse and is mainly composed of mosses (∼ 76 % of the understory vegetation in dry weight), shrubs (∼ 15 %, mainly Vaccinium myrtillus [L.] and Rubus species), and ferns (∼ 8 %). Figure 1 gives a distribution of dominant tree species in most of the target area. This classification is based on multispectral images acquired with a drone in 2018 (Lanssens, 2019). The dominant winds blow from the south-west (sector dominated by European beech) and the north-east (sector dominated by Norway spruce and Douglas fir). The footprint climatology was obtained using the model by Kljun et al. (2015) and is shown in Fig. 1. Within the 70 % cumulative footprint, the distribution of tree species is dominated by Norway spruce (38 %) and European beech (36 %), followed by Silver fir (14 %), Douglas fir (9 %), and Scots pine (2 %).

The study site is located in a rural area with low anthropogenic activity, except for a sawmill 3 km south-west of the flux tower and two small industrial hubs around 7 km north-east and south-east. ICOS-related measurements are carried out on the 51 m high flux tower and its close surroundings. Another measurement station, operated by the Walloon Scientific Institute for Public Service (ISSeP) – the regional environmental authority – is located in the same forest, approximately 250 m from the flux tower. Measurements carried out at the ISSeP station are detailed in Sect. 2.5.2. More information about the study site are available in Aubinet et al. (2001, 2018). Note that all times reported in this paper are given in local time (LT), defined as Central European Time (UTC+1) without daylight saving time (DST).

2.2 Experimental setup

Three setups were operated at BE-Vie from 2022 to 2024: the TOP system, the TRUNK system, and the PROFILE system. These are described below, and details about the related analytical techniques are provided in Sect. 2.3, while flux computations are discussed in Sects. 2.3.3 and 2.4.

2.2.1 TOP system

To characterize the bidirectional fluxes of BVOCs and O3 above the canopy, a first setup was installed at the top of the 51 m high flux tower (level H7 in Fig. 2). Flux measurements were performed using the eddy covariance (EC) technique, which is based on fast measurements of the vertical wind velocity and the mixing ratio of the tracer of interest.

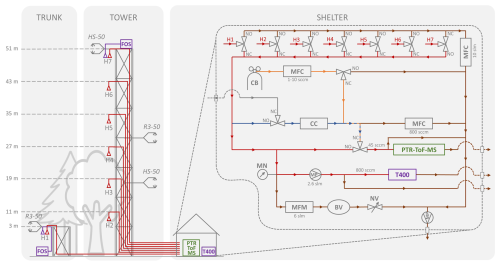

Figure 2Schematic representation of the concentration and sonic anemometer profile setup, including a zoom on the pneumatical system. Instruments include: FOS – fast ozone analyser; T400 – slow ozone analyser; PTR-ToF-MS – fast VOC analyser; HS-50 & R3–50 – sonic anemometers; CB – calibration bottle; MFC – mass flow controller; CC – catalytic converter; MN – manometer; MP – membrane pump; MFM – mass flow meter; BV – buffer volume; NV – needle valve. Line colours indicate function: purple – ozone line, red – ozone/VOC line, blue – background line, orange – calibration line, brown – exhaust line. The positions of the solenoid valves are indicated by NO (normally open, i.e. open without electrical activation) and NC (normally closed, i.e. open only when electrically activated).

At the top of the tower, a 3D HS-50 sonic anemometer (Gill Instrument Ltd, UK) was used to record 3D wind components at a frequency of 10 Hz (see Table 1 for a summary of the instruments used). To measure BVOC and O3 mixing ratios, ambient air was sampled at level H7 close to the HS-50 measurement volume and pumped to a wooden shelter at ground level through a 60 m long and 6.4 mm inner-diameter PFA (perfluoroalkoxy alkane) tubing (Fluortechnik-Deutschland, Germany) at a flow rate of about 10 SLM – litre per minute, under standard conditions of pressure (100 kPa) and temperature (273.15 K). The residence time in this tubing is estimated at ∼ 10 s. This line was heated and thermally insulated to prevent condensation. A PFA raincap and a PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) particulate filter (2 µm pore size, Pall Corp, Port Washington, NY, USA) were placed at the tubing inlet. The filter was replaced monthly.

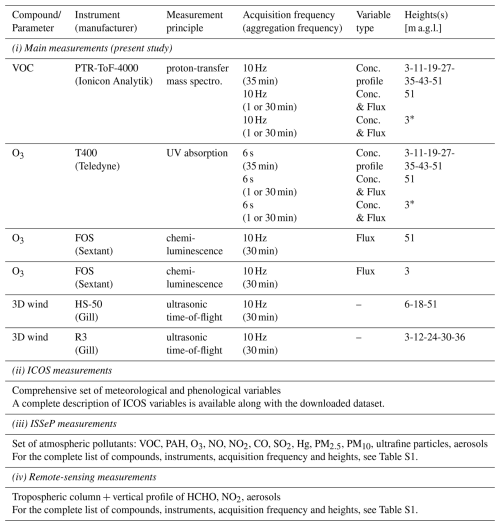

Table 1Overview of instruments and related measurements. The access to the four distinct datasets (groups i–iv) are given in the code and data availability section.

* Not available in 2022.

In the shelter, ambient air was subsampled towards a PTR-ToF-MS 4000 (Ionicon Analytik GmbH, Innsbruck, Austria) instrument for fast measurements (10 Hz) of VOC mixing ratios. On the same line, air was also subsampled towards a T400 UV Absorption O3 analyser (Teledyne Technologies Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) for low-frequency measurements (every 6 s) of ozone. Section 2.2.4 provides more information about the pneumatic system inside the shelter.

The T400 instrument was used to deliver calibrated concentrations of ozone, but its measurement frequency was not suitable for flux computation. Therefore, an additional Fast Ozone Analyser (FOS, Sextant Technology Ltd, Wellington, New Zealand) was installed at the top of the tower. Ambient air was sampled close to the sampling point of the VOC/O3 line and brought to the FOS analyser through a 6.5 m long and 6.4 mm inner-diameter PFA tube with a flow rate of about 3.5 SLM. This line was also heated, thermally insulated, and protected by a PFA raincap and a PTFE particulate filter. The FOS signal was recorded at a frequency of 10 Hz.

2.2.2 TRUNK system

The lowest level of the VOC/O3 profile (H1, see Sect. 2.2.3) was located on a 3 m high mast installed in 2022 in the European beech sector, approximately 10 m west of the tower. Ambient air was sampled through a 60 m long tube leading to the shelter. In 2023, a second FOS instrument (5 m long and 6.4 mm inner-diameter PFA tube, flowrate of 3.5 SLM) and a 3D R3-50 sonic anemometer (Gill Instrument Ltd, UK) were added to the 3 m mast to establish a system compatible with EC measurements. This configuration, referred to as the TRUNK system, samples air from within the trunk space of the forest, primarily to characterize the VOC and ozone fluxes exchanged by the soil. However, a small part of this space is occupied by young woody vegetation, shrubs, mosses and ferns, as shown in Fig. 3.

2.2.3 PROFILE system

The characterization of exchange processes inside the canopy is based on two types of profiles: (i) a VOC and O3 concentration profile and (ii) a turbulence profile measured using 3D sonic anemometers. The two 60 m long lines installed for the TRUNK and TOP systems were supplemented by five additional tubes of the same length, material and diameter, resulting in a concentration profile with seven evenly distributed sampling points. The measurement heights for levels H7–H1 are given in Table 1 and Fig. 2. All of these lines were made of PFA, heated, and connected to a manifold inside the shelter. The TOP and TRUNK sonic anemometers were supplemented by an additional HS-50 and R3-50 sonic anemometers, respectively mounted on 3 and 2 m long aluminium arms attached to the tower. These sonic anemometers were rotated over the 3-year measurement period to characterize turbulence at as many heights as possible. The corresponding heights are listed in Table 1.

2.2.4 Pneumatical setup

In the shelter, a manifold system made of seven three-way PFA solenoid valves was used to sequentially sample ambient air from levels H7 to H1. During TOP (H7) and TRUNK (H1) system measurements, air was sampled for at least 30 min to apply the EC method. In PROFILE mode, air was sequentially sampled from levels H6 to H1, for respective periods of 5 min. To obtain a complete concentration profile, the last 5 min of a preceding TOP mode were included in the PROFILE cycle.

Downstream of the manifold, air was subsampled towards the PTR-ToF-MS and T400 instruments. Due to the pressure drop along the 60 m sampling line, the inlet pressure of the T400 becomes too low for proper operation. To compensate for this, a PTFE-coated membrane pump (KNF N86KT.18, KNF Neuberger GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) was installed upstream of the T400 to bring the sampled air to local atmospheric pressure. The PTR-ToF-MS requires regular calibration and background measurements. For background measurements, the ambient air subsampled from the H7 line was sent through a catalytic converter (Parker, type HPZA-3500, Haverhill, MA, USA) to remove VOC before being analysed. For calibration, a user-defined flow rate of a VOC standard (Apel-Riemer Environmental Inc., FL, USA) was mixed with zero-VOC air from the background line. More details on VOC quantification are given in Sect. 2.3.2. A total flow of about 10 SLM was pumped through the selected sampling line by a membrane pump (MD12C NT, Vacuubrand, Germany) and manually controlled by a needle valve. A buffer volume was added between the needle valve and the flow meter to dampen the flow and pressure variations caused by the pump. The non-selected sampling lines were continuously flushed with ambient air to allow for fast switching between lines.

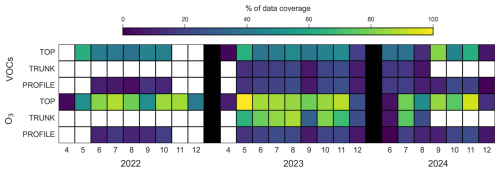

2.2.5 Data coverage

During the 3 years of measurements, the VOC and O3 analytical instruments were operated as simultaneously as possible, with particular emphasis on the spring, summer, and autumn periods. Figure 4 summarizes the monthly percentages of half-hour intervals that were successfully measured by each system.

Figure 4Percentage of half-hours covered per month and per year for measurements shared between the TOP, TRUNK and PROFILE systems.

In 2022, the PTR-ToF-MS and the T400 instruments sequentially measured 30 min periods at the TOP level and in PROFILE mode. On average, TOP measurements were performed 3.5 times more frequently than PROFILE measurements. Background VOC measurements were systematically performed for 30 min every 4 h, and single-point VOC calibrations were performed every 3 to 4 d. These procedures limited data coverage for other measurement systems.

In 2023 and 2024, TRUNK measurements were added. In this updated sequence, TOP measurements occurred on average 2.5 times more frequently than PROFILE or TRUNK measurements.

Overall, ozone flux measurements at the TOP and TRUNK levels were more frequent than those for VOCs, since the two FOS analysers operated continuously, while the PTR-ToF-MS had to alternate between levels. This will be discussed further in Sect. 2.4.2.

2.3 VOC measurements

2.3.1 PTR-ToF-MS settings

The PTR-ToF-MS instrument was operated in the H3O+ mode. Air was subsampled by the instrument through a 1.2 m long silcosteel capillary (1 mm inner diameter). The drift tube reactor was operated at a pressure of 3.3 hPa and a reduced electric field () of 135 Td (1 Townsend = 10−21 V m2). Both the inlet line and the drift tube reactor were kept at 353 K. The inner part of the drift tube has an EVR (Extended Volatility Range, Piel et al., 2021) coating to minimize losses of sticky compounds to the surfaces of the reactor. A hexapole ion guide is used to efficiently transport ions from the drift tube to the mass analyser section.

The Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer was operated at an extraction time and frequency of 2 µs and 40 kHz, respectively, allowing for a mass-to-charge () range of 7–392. A small flow of diiodobenzene, provided by a built-in permeation device (PerMaSCal, Ionicon Analytik GmbH, Innsbruck, Austria) was constantly added to the drift tube for frequent internal mass scale calibration based upon the position of protonated diiodobenzene (at 330.848), its fragment (at 203.943), and HO+ (at 21.022) on the detector. Time-of-flight mass spectra were integrated over 100 ms to allow for EC flux calculations. A maximal mass resolution () of 4200 was obtained for the high mass range. At 59.049 (protonated acetone) and 137.132 (protonated monoterpenes), the mass resolution was about 3400 and 3800, respectively. The peak area related to primary ion signals ranged from 8766–25554 ( 21.022 related to H3O+) to 11–619 ( 38.033; H3O+(H2O)) counts per second (cps) over the 3 years of measurements. By considering the relative transmission of the instrument at 21.022 and 38.33 (respectively 9 %–15 % and 29 %–43 % relative to the transmission at 180.937), together with the relative abundance of the HO+ and HO16O+ + DHO isotopes (respectively 488 and 669), this results in a transmission-corrected source ion count rate of 40×106–110×106 cps.

2.3.2 Signal processing and quantification

Peak identification and integration of recorded spectra were performed on a near-daily basis with the Ionicon Data Analyzer software (IDA Müller et al., 2013; 2022, v 1.0.0.2; 2023, v 2.0.1.2; 2024, v 2.2.1.1). Subsequent data processing was performed in a python-based framework referred to as the Peak Area Processing software (PAP) which was used for non-targeted peak selection, instrument characterization, and quantification of mixing ratios with related uncertainties at both 10 Hz and 1 min time resolution. The PAP software is publicly available (https://github.com/bverreyk/PeakAreaProcessing, last access: 13 January 2026, Verreyken et al., 2025a) and a general overview of its main processing steps is given below. An extended version of the discussion on how VOCs were quantified and details on the configuration of the PAP software and instrument operations can be found in Sect. S2.

Mass selection

The mass scale was calibrated in the IDA software every 60 s and peak-shapes were considered stable over the course of 1 h. Independent peak identification was performed for each IDA analysis with up to 8 values identified per peak system (collection of isobaric peaks with the same nominal mass). A peak system was only considered for analysis if its maximum ion signal intensity exceeded 0.1 cps. To obtain a list of non-targeted ratios, Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (Ester et al., 1996), or DBSCAN, was employed to identify mass-to-charge ratios where peaks were regularly observed. An automated selection of ion values has been performed based on (i) the width of the DBSCAN intervals centred around the mass (stability of peak identification by IDA), (ii) the fraction of data above the limit of quantification (significance of concentrations), and (iii) the localization (interpretability of the data). Afterwards, a manual selection to discard values related to isotopes or hydrated ion species was done. Compound attribution was performed by making use of PTR-MS databases (Pagonis et al., 2019; Yáñez-Serrano et al., 2021) and measurements reported at ecosystem sites (Kim et al., 2010; Hellén et al., 2018; Schallhart et al., 2018; Pfannerstill et al., 2021) to identify the compounds most likely to contribute to the observed signal.

Instrument characterization

Calibrations were performed every 3–4 d to characterize the instrument transmission and calculate calibration factors for compounds included in the calibration bottle (Table S2). Instrument transmission (relative to the one at 21.022) was calculated using a subset of compounds (associated to 33.033, 42.034, 45.033, 59.049, 79.054, 93.070, 107.086, and 180.937) included in the calibration bottle (Fig. S2). The transmission curve between 21.022 and 180.937 was defined through linear interpolation of transmissions obtained during calibrations. At high , the transmission curve becomes more stable and we assumed a constant behaviour ().

Mixing ratio calculation

The mixing ratio of compounds was calculated using either the kinetic or the calibration approach, similar to the discussion in the ACTRIS measurement guidelines for VOC analysis with PTR-MS instruments (Dusanter et al., 2025). In both cases, integrated peak areas (cps) obtained from IDA were corrected for ion transmission, and normalized with respect to a source ion peak area of 106 cps to account for variations in the source ion production. VOC volume mixing ratios (VMR) were calculated by dividing the background-subtracted transmission-corrected normalized peak areas (tc-ncps) by the compound-dependent sensitivities (tc-ncps ppbv−1). For compounds present in the calibration standard, sensitivities were calculated at every calibration. At values not related to compounds available in the standard, sensitivities were derived from calculated H3O+/VOC reaction rate constants and product ion distributions, as well as drift tube reactor conditions, as explained in more detail in Sect. S2.1.3.

Uncertainty quantification

The expanded or combined uncertainty (with a coverage factor of 2) of the calculated VOC mixing ratios combines both the precision of the peak areas and systematic errors (accuracy) associated with instrument calibration or sensitivity calculations:

The precision of the peak areas can be determined from Poisson statistics and approximated by the square root of the integrated counts over the measurement interval. However, peak areas obtained with IDA are inherently baseline-subtracted (Müller et al., 2013) and can be negative for small peaks, hereby invalidating the above-mentioned approach. This issue occurs especially during zero measurements and is more prevalent when considering data acquired at high sampling frequency, where statistical uncertainties are inherently higher. For 1 min averaged data, the precision was therefore approximated by the precision of the mean 100 ms peak area over the variability interval, assuming a normal distribution.

The systematic uncertainty (accuracy) of the volume mixing ratios for compounds included in the calibration standard was obtained by combining the stated uncertainty on the mixing ratios of those compounds in the standard (∼ 2.5 %) with the uncertainty of the dilution factor (∼ 1.5 %). A conservative systematic uncertainty of ∼ 56 % was used for mixing ratios quantified using the kinetic approach, due to large uncertainties on the calculated H3O+/VOC rate constants (∼ 25 %) and on the product ion distributions (∼ 50 %). This accuracy is close to results by Sekimoto et al. (2017) which showed that measured sensitivities agreed within 20 %–50 % with theoretical sensitivities calculated using molecular mass, elemental composition, and functional group of the analyte.

For the combined uncertainty, Simon et al. (2023) included an additional 5 % uncertainty due to relative humidity effects. However, as the H3O+(H2O) signal was generally less than 3 % that of H3O+ + H3O+(H2O) (Fig. S4), the impact of relative humidity was assumed to be small and this additional uncertainty is not considered here.

The limit of detection (quantification) for concentrations is defined as three (ten) times the precision of the associated background measurement, of which we only considered the last 5 min to assure equilibrium. The mean and standard deviation of the measurement distribution during these 5 min were used to define the background value and its precision, respectively.

More details on uncertainty characterization are given in Sect. S2.1.4.

2.3.3 Flux computation

Half-hourly VOC fluxes were computed following the general procedure commonly used for eddy covariance flux calculation. This included raw data despiking and gap filling, block averaging, coordinate rotation of wind components, time-lag estimation by maximizing covariance and data shifting, covariance calculation and correction for high-frequency spectral losses (Aubinet et al., 2012).

EC fluxes are commonly filtered to remove data collected under low-turbulence conditions, particularly for CO2 fluxes, using a friction velocity (u*) threshold. However, given the different nature of VOC exchange processes compared to CO2, no u* filtering was applied in this study. Additional information and justification for this choice are provided in Sect. S3.1.

All flux computations, from raw sonic anemometer data and processed VOC concentrations, were performed using the GEddySoft (“Gembloux Eddy-covariance Software”) software. GEddySoft was initially developed from the open source innFlux software (Striednig et al., 2020), which supports both conventional and disjunct eddy covariance analyses. The original MATLAB® code was converted to Python, and the software has been continuously expanded with additional data handling and flux processing features. For this study, version 4.0 of GEddySoft was used and is publicly available (https://github.com/BernardHeinesch/GEddySoft, last access: 13 January 2026), along with a test input dataset (https://doi.org/10.18758/IYPN6FNM, Heinesch et al., 2025).

Unless explicitly stated, the same procedure was applied to both the TOP and TRUNK systems. One exception concerns the tilt correction of the sonic anemometers: the double rotation method was used for the TOP system, while the sector-wise planar fit method was applied to the TRUNK system. Below-canopy turbulence was sometimes low, so applying the double rotation method at the half-hourly scale could result in high rotation angle values and erroneous fluxes (notably artificially high absolute fluxes; see Fig. S6, where the effect is most visible for O3 fluxes). The sector-wise planar fit method, which computes a single set of tilt angles based on long-term time series, was able to solve this issue and was therefore applied to TRUNK fluxes (with tilt angles determined for 2023 and applied to both 2023 and 2024). Details about both methods are given in Wilczak et al. (2001). The structure at the back of the sonic anemometer used for the TOP system (HS-50) can act as an obstacle to airflow. Consequently, fluxes coming from a ±10° wind sector around the sonic anemometer arm were discarded, following the ICOS protocol (Sabbatini et al., 2018). No filtering was applied to TRUNK fluxes, which were measured with an omnidirectional sonic anemometer.

The main steps of flux computation described above were also applied to ozone fluxes. However, considering the differences in the measurement setups, several methodological aspects diverged between the two flux calculations. These aspects are detailed in the present Section for VOCs and in Sect. 2.4.1 for ozone.

Lag time determination

In EC measurements, the lag time represents the time delay between instantaneous measurements of the vertical wind component w and the tracer concentration c, arising, among other factors, from differences in electronic signal processing, spatial separation between wind and scalar sensors, and air transport through sampling lines (Aubinet et al., 2012). When w and c are recorded on separate data logging systems, it is therefore good practice to regularly synchronise their internal clocks in order to minimise clock drift, which would otherwise introduce an additional temporal offset between the two time series.

In the present set-up, w and c were recorded on two distinct laptops, which were frequently synchronised using a GPS time reference (MR-350, GlobalSat WorldCom Corporation, Taipei Hsien, Taiwan). However, while the computers themselves remained synchronised, the internal data acquisition system (DAQ) of the PTR-ToF-MS relied on a separate internal time axis, which exhibited a non-linear time drift, the origin of which could not be fully identified. As a consequence, the timestamps assigned to the mass spectra by the DAQ progressively became de-synchronised from the sonic anemometer time series. To overcome this issue, the evolution of this drift was monitored during each field campaign and used to correct for the DAQ-related time drift during post-processing. In addition, the DAQ was regularly restarted during the campaigns in order to minimise the accumulation of this time drift and reset it to zero.

After correction for the DAQ-related time drift, the lag time between w′ and c′ was determined by maximizing their covariance within a physically plausible window (11–15 s) for each flux window and each . If the maximum covariance occurred at the edge of the window, a fixed lag of 13 s was assigned. This default value corresponds to both the centre of the window and the median lag time observed for monoterpenes (VOC with the highest signal-to-noise ratio, SNR) across the entire measurement campaign. It is also consistent with expectations based on tube dimensions and flow rates (first-order estimate of the residence time, ∼ 10 s).

To refine lag estimation and reduce spurious detections under low SNR conditions, the covariance function was smoothed using a 15-sample (1.5 s) moving average prior to the search. This approach, as recommended by Taipale et al. (2010) and Langford et al. (2015), effectively mitigates “mirroring” effects associated with low fluxes while preserving sensitivity to time-varying lags.

The stability of lag times was assessed visually across all campaigns and for all values. Under high SNR conditions, lag times were found to be highly stable, with the exception of two ions species: 33.033 (protonated methanol) and 47.049 (protonated ethanol) (as well as H3O+ and its hydrates, which were excluded from the analysis). For these two , a small but systematic dependence on air relative humidity (RH) was observed. When RH exceeded 95 %, the lag time tended to increase in absolute value, shifting from −13 up to −20 s (data not shown). Consequently, the centre of the lag-search window was parametrized as a function of RH for these two ions.

Correction for flux high-frequency losses

An experimental co-spectral approach was adopted to correct for high-frequency attenuation (Aubinet et al., 1999; Wintjen et al., 2020), and was applied in three steps. First, a transfer function was derived by dividing the normalized mean co-spectrum of wc (attenuated) by that of wT (considered ideal), and was then fitted using a Lorentzian function to obtain a single cut-off frequency. Second, to derive a flux correction factor at the half-hour scale, the area under the wT co-spectrum (representing the non-attenuated flux) was divided by the area under the same co-spectrum multiplied by the transfer function (representing the attenuated flux). Third, these correction factors, obtained for a limited number of half-hours after drastic data filtering (see Sect. S3.3), were sorted and averaged into five wind speed classes for unstable and stable atmospheric conditions separately. These two lookup tables were then used to assign a correction factor for each individual half-hour, depending on its wind speed and atmospheric stability. The procedure was applied to monoterpenes to benefit from their high SNRs. Since the correction characterizes the experimental setup in combination with the flow characteristics, without any expected compound-specific aspects, it was then applied to all other compounds.

The choice of a co-spectral, rather than spectral, approach was motivated by its capacity to empirically integrate all causes of signal attenuation – tube damping, instrumental response, and sensor separation – without relying on a theoretical transfer function for sensor separation. Furthermore, our method does not require a reference co-spectrum, whose formulation and ability to represent real conditions at the site are often subject to discussion. It should be noted that, following the recommendations of Peltola et al. (2021), the square root of the transfer function was used rather than the transfer function itself to derive both the cut-off frequency (step one) and the correction factor (step two), in order to correctly account for the phase shift introduced by our lag-time determination method.

For the TRUNK system, step one could not be applied due to generally low fluxes and associated low SNRs across all compounds. However, given that the cut-off frequency reflects the setup alone and that the TRUNK and TOP configurations were identical, the cut-off frequency derived from the TOP system was applied. Steps two and three were executed independently for the TRUNK level, as atmospheric turbulence is location-specific.

This procedure led to correction factors ranging from 1.10 to 1.26 for the TOP system, and from 1.10 to 1.40 for the TRUNK one. More details are provided in Sect. S3.3.

Flux quality control

Flux quality was assessed at two levels. First, the high-frequency inputs used for flux computation – VOC mixing ratios and sonic anemometer data – were (in)validated based on statistical tests developed by Vitale et al. (2020). These tests have the advantage, compared to the more traditional tests of Vickers and Mahrt (1997), of being completely automatable, not requiring user choices on, for example, threshold values. Adapted from the open-source RFlux toolbox (https://github.com/icos-etc/RFlux, last access: 3 July 2025), they were integrated in our GEddySoft processing pipeline. The combination of the tests present in RFlux and described in Vitale et al. (2020) (HF5, HF1, HD5, KID) led to the creation of an instrumental flag, hereafter named flag_instr. Only a few half-hour periods were flagged for instrumental issues (Fig. S12), with a maximum of 12 % of fluxes flagged for 80.058 in the TOP system.

Other instrumental tests available in the RFlux toolbox – including AL1, DIP, and DDI – although implemented in the ICOS standard processing pipeline, were not applied here. These tests tended to flag excessively long periods, including VOC fluxes with low SNR, as well as those displaying clear and reasonable diurnal dynamics. Furthermore, they have not yet been described in peer-reviewed literature and have never been validated for compounds with inherently lower SNR such as VOCs. For these reasons, they were considered unsuitable for our dataset and were excluded from the present analysis.

Second, a quality flag was assigned to the computed fluxes based on steady-state (stationarity) and integral turbulence characteristic tests, following the methodology developed by Mauder and Foken (2004). This flag, named flag_MF (for Mauder and Foken), can take three values: 0 indicates high-quality fluxes; 1 corresponds to fluxes suitable for general analysis; and 2 denotes poor-quality fluxes. For stationarity, we preferred the test proposed by Mahrt (1998) over that of Foken and Wichura (1996), as it proved more effective at flagging anthropogenic influences (see Sect. 2.3.4). Fluxes flagged at level 2 were discarded for the remainder of this study. The percentage of half-hours discarded according to flag_MF reached up to 20 % for the TOP system and 33 % for the TRUNK system, in both cases for 137.132. This filtering is primarily due to the influence of anthropogenic sources (see Sect. 2.3.4), an effect further described in Sect. S3.4.

A combined flag (flag_tot) was created by integrating flag_instr and flag_MF, as well as an additional flag (flag_plume) designed to filter out periods affected by anthropogenic emissions (see Sect. 2.3.4). Only fluxes passing all three flag criteria were assigned a value of 0 for flag_tot and retained for further analysis in this study.

Correction for density fluctuation

VOC fluxes can be biased by fluctuations in temperature and water vapour, which affect air density. These effects can be accounted for using the Webb–Pearman–Leuning (WPL) corrections (Webb et al., 1980). In our setup, temperature fluctuations were considered attenuated due to the length of the sampling lines, which largely exceeded the 3.20 m minimum recommended by Rannik et al. (1997). Moreover, during flux measurements using a PTR-ToF-MS, Loubet et al. (2022) reported that corrections for water vapour fluctuations were very small (less than 2 % for 75 % of the time). For these reasons, WPL corrections were not applied to VOC fluxes in this study.

Flux storage

To obtain the net exchange of VOCs, a storage term should be added to the turbulent flux. The storage flux represents the temporal variation of the mixing ratio of the compound below the EC measurement height, and is expected to be non-negligible for tall towers and under low turbulence conditions, such as at night. The storage term was calculated following the procedure described by Montagnani et al. (2018):

where Si is the storage flux for tracer i (nmol m−2 s−1), is the dry air density of layer j, is the temporal variation of mixing ratio for tracer i (nmol mol−1) at height j over a time period Δt (s), and Δzj is the thickness of layer j (m). Temporal changes in mixing ratios were derived from concentration profiles measured every 2 to 2.5 h.

The resulting storage fluxes exhibited erratic temporal dynamics and, for many VOCs, their magnitudes often exceeded those of the turbulent flux. We consider that calculating temporal variations in concentrations over 2 to 2.5 h intervals is unlikely to accurately capture true storage processes within the canopy, particularly for reactive compounds with short atmospheric lifetimes. This limitation likely results in unreliable storage flux estimates. To avoid degrading the overall data quality, storage fluxes were therefore not included in the net flux calculation.

2.3.4 Filtering of anthropogenic sources

Over the 3 years of measurements, we occasionally observed abnormally high VOC mixing ratios under winds from the 230–270° sector. This phenomenon had already been reported for monoterpenes and methanol during earlier campaigns in 2009 and 2010 (Laffineur et al., 2011, 2012), and was attributed to a wood panel factory located 3 km south-west of the tower.

In the present study, this anthropogenic influence was mostly observed at night, yet occurred irregularly and did not affect all VOCs uniformly, with many of the detected ions not being impacted at all. The most affected ions included protonated monoterpenes (e.g. 137.132), as well as fragments and isotopes, sesquiterpenes, and potential derivatives such as 135.117 (likely p-cymene). A few low molecular weight oxygenated compounds such as methanol and acetic acid were also affected, though to a lesser extent. During plume events, the affected VOCs exhibited elevated mixing ratios and mixing ratio variances, and occasionally large negative fluxes (i.e. apparent deposition), which are not expected for compounds like monoterpenes.

To identify such episodes, Laffineur et al. (2011) proposed an upper threshold on the 30 min variance of monoterpene mixing ratios in the 230–270° wind sector, assuming that incomplete mixing between anthropogenic and biogenic sources led to higher variability in mixing ratios. However, extending this method would require manually identifying all impacted ions and setting compound-specific thresholds, which is subjective and impractical.

To address this limitation, we developed an automatic flagging procedure. For each VOC, we computed q99, the 99th percentile of its 30 min mixing ratio variance calculated across all wind directions except 180–300°, which is subject to sawmill influence. Then, any half-hour within the 180–300° sector with a variance exceeding q99 was flagged as potentially affected (Fig. S11). This approach successfully identified affected VOCs (7 % of half-hours flagged for monoterpenes or methanol, see Fig. S12) while leaving unaffected compounds mostly untouched (e.g. only 0.3 % flagged for isoprene). Although many spoiled half-hours had already been identified by the stationarity test (flag_MF), this new flag_plume completed the identification of such events.

Two mechanisms may account for the influence of the sawmill on local fluxes despite their relatively long distance from the tower (3 km). First, although the factory typically falls within an area with a low relative contribution to the measured flux compared with the surrounding forest, its clear influence observed in the fluxes suggests that the sawmill would constitute a strong VOC source. This influence is most evident at night, when more stable atmospheric conditions enlarge the flux footprint, thereby increasing the relative weight of the factory on the observed fluxes. A second explanation is that even when the factory lies in a footprint region with very low contribution, VOC-rich air masses emitted by the factory may still be advected toward the tower. In such cases, the resulting high local concentrations can generate apparent downward fluxes, despite the source being located outside the main footprint area.

While some fluxes exhibited a well-defined lag time during plume events – suggesting real turbulent deposition, as also observed by Bamberger et al. (2011) – these episodes showed erratic dynamics and no consistent relationship with environmental drivers. Therefore, to focus the analysis on biogenic VOC exchange, we excluded flagged fluxes from further processing. Similarly, concentrations flagged by flag_plume were not considered in the rest of this study.

2.3.5 Identification of significant exchanges

Among the retained by the DBSCAN algorithm, not all ions exhibited significant fluxes. To determine whether a compound is significantly exchanged, it is common practice to compare half-hourly fluxes with their corresponding flux limit of detection (LODf). In this study, LODf was estimated at the 99 % confidence level as three times the random flux error, calculated in GEddySoft following the method described in Finkelstein and Sims (2001).

Extrapolating such comparisons from the half-hourly scale to longer periods, in order to assess whether a compound is consistently exchanged, is not straightforward. Loubet et al. (2022) addressed this by comparing the mean flux of VOCs with an averaged LODf, itself calculated as the square root of the sum of squared individual LODf values, divided by the number of records (Langford et al., 2015). While this approach allows a simple comparison over an entire campaign, it may fail to detect compounds significantly exchanged only during short periods.

To overcome this limitation, we developed a novel three-step methodology, applied individually to all values. First, each half-hour period was flagged as significant if the absolute flux exceeded its LODf. Second, a day was considered significant if at least 25 % of the daytime half-hourly periods (defined as 08:00–20:00 LT) were significant. Finally, we considered the number of consecutive significant days. Given that the mechanisms responsible for VOC emission or deposition are unlikely to occur on a single day, we selected values for which at least 3 consecutive days of significant exchange were observed during the measurement period.

2.4 Ozone measurements

2.4.1 Raw ozone fluxes

Ozone flux measurements were performed with a fast ozone analyser (FOS). In the instrument, O3 molecules present in ambient air react with a coumarin disc (solid or dry phase), thereby producing a light signal (chemiluminescence reaction) recorded in units of Volts (V) at a high frequency (10 Hz). Coumarin discs were produced from silica plates impregnated with a solution of coumarin, methanol and ethylene glycol. Since the efficiency of the chemiluminescence reaction decreases over time, coumarin discs were replaced on average once a week during the 2022 and 2023 campaigns. In 2024, disc replacements were less frequent considering the important workload (up to 36 d between disc replacements).

Raw ozone fluxes were computed using the EddyPro® software, applying the same processing steps as described in Sect. 2.3.3. As for VOCs, no u* filtering was applied. Given the differences in the measurement setups, certain aspects of the flux computation differ and are detailed below.

Lag time determination

As for VOCs, the physical lag time between w′ and c′ was determined by maximizing the covariance function within a predefined lag window. When no clear extremum was found within this window, a nominal lag value was applied. Due to the higher SNR of O3 fluxes compared to many VOCs, no smoothing of the covariance function was necessary. Across the different measurement campaigns, the median lag time was close for the O3 TOP and TRUNK systems, with values of 2.2 and 2.0 s, respectively.

Correction for flux high-frequency losses

The three-step experimental co-spectral approach applied to VOCs was also used for ozone. The only difference is that, due to more pronounced ozone fluxes measured at the TRUNK level compared to VOCs, it was possible to determine a cut-off frequency for the TRUNK system.

Correction factors ranged from 1.12 to 1.37 for the TOP system, and from 1.03 to 1.28 for the TRUNK one. Further details are provided in Sect. S3.3.

Flux quality control

An instrumental flag was generated by combining the individual tests developed by Vickers and Mahrt (1997) and implemented in EddyPro®. The attack angle and non-steady wind tests were excluded, as they tended to over-flag data that did not appear problematic upon visual inspection. Very few half-hour periods (<1 %) were affected by instrumental issues (Fig. S12).

EddyPro® also computes a flux quality flag similar to the previously described flag_MF, based on the stationarity test of Foken and Wichura (1996). Over the 3-year period, 9 % of the fluxes were flagged as level 2 (poor quality) for the TOP system, and 17 % for the TRUNK system (Fig. S12).

No influence from the wood factory was detected in the ozone data; therefore, no flag_plume was applied. Data flagged by flag_tot were excluded from further analysis in this study.

Correction for density fluctuation

From the original WPL equation (Webb et al., 1980), we neglected temperature fluctuations – assumed to be attenuated through the sampling tubing, as for VOCs – and only assessed the impact of water vapour fluctuations. The latter resulted in a correction of less than 1 % of the raw fluxes on average. This value is much lower than the one reported in Gerosa et al. (2022a) – where temperature-related corrections could not be neglected considering the large-diameter tubing – and also well below our flux random uncertainty estimated according to Finkelstein and Sims (2001). For these reasons, no WPL correction was applied.

Flux storage

The ozone storage was computed with Eq. (2). For TOP storage, 7 layers were considered (H1 to H7, see Fig. 2). Profile measurements were taken every 2 or 2.5 h, so half-hourly storage values were linearly interpolated between adjacent measurements. Since profiles were not continuously scanned throughout the measurement campaigns, a gap-filling approach was required. For TOP storage, we used the storage computed from TOP mixing ratio (which was available at least once every three half-hours) as a proxy for the actual storage term. In combination with other predictors (friction velocity u*, air temperature, incoming PPFD at the top of the canopy, hour of the day, and month number), we trained a Random Forest regression model to estimate and gap-fill storage fluxes derived from the concentration profile. This procedure represents an improvement over the methodology used by Aubinet et al. (2018), who employed look-up tables to gap-fill missing storage data.

No model was required to gap-fill TRUNK storage fluxes. Since only one layer was considered, the storage flux was computed directly when the T400 was in PROFILE mode (using level H1) or TRUNK mode. The missing half-hour values were linearly interpolated between adjacent data points, provided that gaps were shorter than 3 h.

Unlike for VOCs, ozone storage showed a consistent diel pattern (Fig. S14, similar to that observed by Finco et al., 2018). We therefore decided to add the storage flux to the calibrated turbulent flux (calibration described in Sect. 2.4.2) to obtain the net ozone flux.

2.4.2 Ozone flux calibration

Since the FOS analyser provides only voltages (V) proportional to the ozone concentrations, the raw fluxes were calibrated using a T400 UV absorption analyser, which delivers absolute and stable O3 mixing ratios in ppbv (nmol mol−1). The T400 instrument was calibrated annually before each measurement campaign, and automatic zero and span checks were performed nightly to monitor potential drifts.

As noted in Muller et al. (2010) and Zhu et al. (2015), calibration procedures for FOS-based ozone fluxes are rarely detailed, despite their significant impact on data quality. The FOS analyser's sensitivity decreases over time due to the consumption of coumarin molecules in the chemiluminescence reaction with ozone. This sensitivity loss is therefore non-linear (Güsten and Heinrich, 1996), varies from one disc to another, and may include an offset between fast and slow signals.

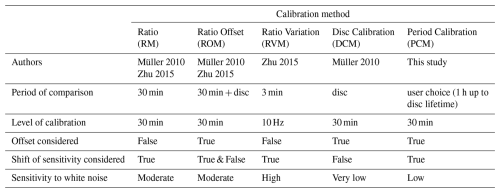

Muller et al. (2010) tested three post-processing calibration methods (see Table 2) by comparing fast and slow ozone signals (1) at the half-hourly scale without considering an offset (Ratio Method, RM), (2) at the half-hourly scale with an offset determined for each coumarin disc (Ratio Offset Method, ROM) and (3) over the lifetime of a coumarin disc using a single regression (Disc Calibration Method, DCM). The RM captures changes in FOS sensitivity more effectively than the DCM, which assumes a stable response throughout the disc lifetime. The ROM represents a compromize; although it applies a half-hourly ratio, the offset remains fixed over the disc's life and may not follow short-term sensitivity shifts.

Zhu et al. (2015) later introduced the Regression Variance Method (RVM), which identifies an optimal averaging window between the FOS and T400 signals using Allan-Werle variance analysis. A 3 min period was found to best track sensitivity changes, but it is also more susceptible to white noise than RM and ROM (30 min windows), and especially DCM (multi-day windows). Both RM and RVM assume zero offset between fast and slow signals – an assumption invalidated by observations from Muller et al. (2010) and Zhu et al. (2015).

An important practical constraint in our study was the limited temporal overlap between fast and slow ozone measurements. The T400 analyser alternated between TOP, TRUNK, and PROFILE modes, preventing continuous half-hourly reference data at any one level. Therefore, we developed a new approach: the Period Calibration Method (PCM). Inspired by DCM, PCM accounts for potential offsets and reduces sensitivity to high-frequency noise. However, unlike DCM, it identifies optimal sub-periods during which the FOS sensitivity remained consistent, allowing more accurate tracking of temporal variability in analyser performance.

With the PCM (Period Calibration Method), calibrated fluxes were computed as:

where Fcal is the calibrated flux (nmol m−2 s−1), Fraw is the raw flux obtained from FOS measurements (V m s−1), β1 is the slope of the regression curve established between the T400 and the FOS measurements (nmol mol−1 V−1), and vmol is the air molar volume (m3 mol−1). Note that while regressions between the T400 and FOS measurements were established with an intercept, this constant term does not intervene in Eq. (3) because it does not correlate with w′.

The overall uncertainty associated with the calibrated flux was estimated from Eq. (3):

where εF,cal is the calibrated flux uncertainty (nmol m−2 s−1), εF,raw is the raw flux random error as estimated by Finkelstein and Sims (2001) (V m s−1), and is the standard error of the slope estimate (nmol mol−1 V−1). The first term under the square root represents the random flux error and the second term represents the calibration error. On average, the calibration error contributed less than 3 % of the total uncertainty. This is in accordance with the observations made by Horváth et al. (2017).

The procedure to establish the regressions between FOS and T400 data comprised four steps:

-

Data validation: FOS and T400 measurements were automatically validated or invalidated based on instrumental parameters such as pressure, flow rate, temperature, and UV lamp status (for the T400). Measurements from the T400 were discarded during the first 3 min following a mode switch (e.g., PROFILE or TRUNK to TOP, PROFILE to TRUNK) due to sensitivity to pressure variations. This delay allowed for pressure stabilization.

-

Data averaging: the FOS signal was averaged to match the T400's resolution at a 6 s timestamp. Unlike the 15 min averaging used by Muller et al. (2010), this finer resolution captured more variability and increased the number of data points for regression. Both T400 and FOS time series were visually inspected to ensure data quality.

-

Data shifting: a time lag was observed between the two 6 s time series, attributed to the difference in tubing lengths (approximately 6 m for the FOS versus 60 m for the T400). To enhance regression quality, the FOS data was shifted by a time lag determined for each regression using covariance maximization. If a clear covariance maximum was not observed, a nominal time lag estimated for the entire measurement campaign was applied.

-

Regression optimization: linear regressions were established using least-squares fits. Equation (3) was applied only when a satisfactory correlation (R2>0.5) between relative (FOS) and absolute (T400) O3 concentrations was achieved, as in Muller et al. (2010). Selecting the optimal regression period was a trade-off between maximizing the number of half-hour intervals meeting the R2 criterion and minimizing calibration-associated uncertainty (Eq. 4). Initially, increasing the regression period (from 1 up to 24 h) enhanced the R2 values and reduced slope errors, as the larger dataset countered random fluctuations (white noise). However, beyond a certain period, shifts in the T400-FOS relationship over time reduced R2, while slope errors plateaued or increased. To balance these behaviours, different regression windows were tested, and for each year and system, an optimal period was selected (Sect. S3.5). Final regression slopes (β1) and their associated uncertainty were then used to calibrate raw fluxes and compute the associated uncertainties.

2.5 Ancillary measurements

2.5.1 Other trace gas and particle measurements

Besides the high temporal resolution VOC and O3 concentration and flux measurements, which are the main focus of this paper, numerous other in situ – both online and offline – measurements of short-lived climate forcers were conducted at the nearby ISSeP air quality station. In addition, remote sensing measurements of NO2, HCHO, and aerosols were carried out from the top of the tower. For completeness, these variables and their associated instrumentation are listed in Table 1.

Furthermore, during the period covered by the high-resolution VOC and ozone datasets, two pan-European Intensive Measurement Campaigns on VOCs and O3 were organized.

The first campaign, coordinated by the EMEP Task Force on Measurements and Modelling (TFMM), took place from 12 to 19 July 2022 and focused on ozone formation under heatwave conditions. It was conducted in close collaboration with the ACTRIS and RI-URBANS European research infrastructures. Among other objectives, this campaign aimed at intensified VOC measurements at selected sites, including the BE-Vie site (BE0007R). In addition to continuous online PTR-ToF-MS measurements, ambient air was sampled daily around noon or in the early afternoon at the ISSeP air quality station for subsequent offline analysis in reference laboratories. Air collected in Silcosteel canisters was analysed by GC-MS, while VOCs adsorbed on TENAX-TA or DNPH cartridges were analysed by GC-MS and HPLC, respectively. More details on the analytical methods, as well as some preliminary data on NMHCs, OVOCs, and terpene concentrations at BE-Vie during this campaign, can be found in Fagerli et al. (2023).

A second EMEP/ACTRIS/RI-URBANS campaign, the “EUROpe-wide Intensive Campaign on Volatile Organic Compounds” (EUROVOC), was held in September 2024. This campaign aimed at gaining deeper insights into VOC emissions, including their temporal variability and chemical speciation, by deploying high-resolution measurements at sites located near emission sources (e.g., urban, industrial, traffic, harbour, and forest areas), including the Vielsalm site.

2.5.2 Sonic anemometer profiles

Raw data from the sonic anemometer profiles were processed using the EddyPro® software to compute key turbulence-related variables along the soil–canopy–atmosphere continuum. These include wind speed, wind direction, friction velocity (u*), the standard deviation of the vertical wind component (σw), turbulent kinetic energy (TKE), Monin–Obukhov length, and atmospheric stability. The Lagrangian integral time scale (TL), which is not included in EddyPro®, was calculated separately as the time integral of the autocorrelation function of w(t), where w is the vertical wind component (Raupach, 1989). These variables – particularly σw and TL – may be especially relevant for inferring the vertical positioning of sources and sinks from concentration profiles (Karl et al., 2004a; Leuning, 2000; Nemitz et al., 2000; Tiwary et al., 2007; Wada et al., 2020; Petersen et al., 2023).

2.5.3 ICOS data

As part of the ICOS network, a series of additional measurements were available at BE-Vie during the three measurement campaigns (Vincke et al., 2025). Turbulent fluxes of CO2 and H2O were measured at 51 m a.g.l. using an infrared gas analyser (LI-7200, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) coupled with the HS-50 sonic anemometer described previously.

Following the ICOS protocol, a comprehensive set of meteorological measurements was collected at BE-Vie, both above and within the canopy. These included air temperature and humidity, atmospheric pressure, incoming and outgoing longwave and shortwave radiation, incoming and outgoing photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), soil temperature and moisture, precipitation, and CO2 and H2O mixing ratio profiles along the tower.

Vegetation development was monitored using images captured every 3 d by a StarDot NetCam SC (PhenoCam) installed at the top of the flux tower and oriented towards the north-west sector (mixture of European beech and Norway spruce). These images were processed using the vegindex Python package (version 0.10.2, https://python-vegindex.readthedocs.io, last access: 5 June 2025, Milliman, 2022) to extract the Green Chromatic Coordinate (GCC), also known as the “greenness index”. Seasonal variations in the GCC provide a reliable proxy for vegetation onset and senescence. Further methodological details are provided in Seyednasrollah et al. (2019).

3.1 Meteorological and phenological conditions

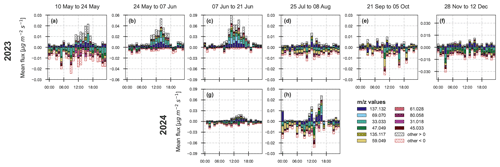

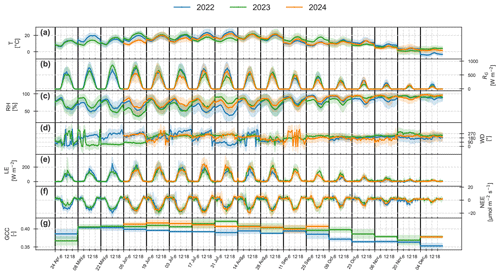

Throughout the three measurement campaigns, certain meteorological and phenological events stand out. While mean diel evolutions appear broadly similar across the years, some distinct year-to-year features are also apparent (Fig. 5).

Figure 5Average diel patterns (in LT) of meteorological and phenological conditions for each 2-week period. Solid lines represent hourly means, and shaded areas indicate the standard deviation around the mean. (a) Air temperature. (b) Incoming global radiation. (c) Relative humidity. (d) Wind direction. (e) Latent heat flux. (f) Net CO2 flux. (g) Greenness index. All variables were measured at the top of the flux tower (TOP system). The greenness index (GCC) was measured once per day, so no diel pattern is shown for this variable and a single mean is provided for each 2-week period.

In 2022, a heatwave that lasted 8 consecutive days was observed from 9 to 16 August. This period was characterized by higher temperatures and radiation compared to the other years, and by lower relative humidity, partly due to very low precipitation (data not shown). From early December of the same year, temperatures were consistently below 0 °C for an extended period of days – a phenomenon not observed in the other years.

The year 2023 was marked by the two hottest months ever recorded in Belgium (June and September). At the end of May and beginning of June, a month-long period of anticyclonic conditions brought warm and dry air from the north-east sector.

Latent heat and carbon fluxes followed the expected patterns for a mixed temperate forest. Photosynthesis (Fig. 5f) and transpiration (Fig. 5e) were enhanced by the increase in temperature and radiation during the transition from spring to summer. The evolution of GCC (Fig. 5g) served as a proxy for leaf expansion of European beech. A strong development of vegetation was observed between 24 April and 8 May. Visual inspection of images captured from the top of the flux tower indicated that budburst occurred around 28 April, with little variation between years. In 2022, the onset of leaf fall was estimated between 20 and 26 October. Warmer conditions in 2023 delayed leaf fall compared to 2022, with observations indicating a period between 2 and 8 November. Phenological images were not available for 2024 to determine the leaf fall period.

3.2 Diversity of VOCs

3.2.1 Number of detected VOCs

In total, 74 values were retained by the DBSCAN algorithm. These ion species are listed in Table S3, along with their chemical formula, tentative compound identification, and parameters related to sensitivity computation.

It is important to note that compounds can give rise to signals at multiple ion masses, which may correspond either to isotopes associated with the chemical formula, to ion species resulting from the fragmentation of nascent excited protonated molecules (i.e., fragment ions), or to protonated water-cluster adducts formed in the ionization region. When reporting total VOC fluxes or concentrations, it is crucial to consider only one ion per compound to avoid double counting.

In general, water clusters and isotopes were not taken into account and have been excluded when compiling the list of ion masses considered (Table S3). One notable exception is protonated benzene ( 79.054), whose peak is entangled with that of protonated hydrated acetic acid ( 79.039). This entanglement is reduced for the 13C isotopes of these ion species (at 80.042 and 80.058, respectively) due to the relatively higher abundance of the protonated benzene isotope. As a result, only the protonated benzene isotope signal was considered for benzene quantification, eliminating any risk of double counting.

In contrast, both protonated molecules and their fragment ions are listed in Table S3 and were included in the concentration and flux database. Keeping both the protonated molecules and their corresponding fragments can be particularly informative, as temporal variations in their relative abundances can reveal shifts in chemical processes, ionization conditions, or source contributions. However, in the analyses and figures that follow, only one signal was taken into account for each VOC to avoid double counting and redundancy. To ensure the best possible quantification, we used the ion signal at the associated with the highest H3O+/VOC product ion yield (Table S3), ending up with a list of 62 VOCs. It should be noted, however, that each of these reported VOCs represents a group of one or more individual chemical compounds contributing to the same signal, as listed in Table S3, and to which a single experimentally determined or estimated sensitivity factor was assigned. Consequently, when referring to the number of VOCs throughout this study, this number should be interpreted as the number of -based VOC groups rather than the exact number of distinct molecular species exchanged by the ecosystem.

From these 62 VOCs, 44 were identified as significantly exchanged at the top of the tower, based on the three-step comparison of fluxes with LODf described in Sect. 2.3.5. The algorithm performed well in identifying ions with clear flux dynamics, with only a few exceptions: one VOC was found by the algorithm but displayed erratic flux patterns ( 97.028 (C5H4O2H+)), while five others exhibited consistent diurnal trends but were not detected by the algorithm – 97.065 (C6H8OH+), 99.044 (C5H6O2H+), 101.023 (C4H4O3H+), 103.075 (C5H10O2H+), and 115.075 (C6H10O2H+). The latter were manually included, and the former excluded, resulting in a final list of 48 VOCs considered significantly exchanged for the TOP system.

In summary, the DBSCAN algorithm retained 74 values corresponding to 62 VOCs, of which 48 showed significant exchange. This number is intermediate in comparison to other studies using a PTR-ToF-MS instrument. Some reported hundreds of ions with significant fluxes: 494 over an orange orchard in California (Park et al., 2013a); 377 above a mixed temperate forest in the USA (Millet et al., 2018); around 200 with a PTR3-ToF-MS above a boreal forest in Hyytiälä, Finland (Fischer et al., 2021); and 123 over a winter wheat field in France (Loubet et al., 2022). In contrast, other studies reported lower numbers than in the present work: 29 in a deciduous forest in Northern Italy (Schallhart et al., 2016); between 10 and 20 over a similar forest in the same region (Jensen et al., 2018); 25 above a boreal forest in Finland (Schallhart et al., 2018); and 18 compounds distributed over 43 ion species at a grassland site in Austria during harvest (Ruuskanen et al., 2011).

These large differences can be explained by the sensitivity of the PTR-ToF-MS instrument but also by the ecosystem type – for example, an orange orchard may emit substantially more VOCs than a temperate forest (Loubet et al., 2022). However, even for similar ecosystems and climatic conditions, Millet et al. (2018) reported six times more significant compounds than in the present study. This raises questions not only about instrumental performance, but also about the methodological choices involved in filtering ions to identify VOC exchanges.

Differences across studies already arise upstream of flux calculations, at the level of ion detection and selection. The number of ions identified by PTR-ToF-MS can vary substantially depending on how fragments, water clusters, isotopes, impurities, and other artefacts are filtered, a process that is often insufficiently described in the literature. In the present work, beyond an initial filtering of water clusters and isotopes, the application of the PAP software further reduced the ion list by retaining only mass-to-charge ratios for which peaks were regularly observed and generally above the limit of quantification.

At a later stage, when computing fluxes, additional methodological choices are introduced, particularly regarding the definition of a flux as being significantly different from zero. While most studies estimate the random flux error from the cross-covariance between vertical wind fluctuations (w′) and concentration fluctuations (c′) at large time lags – where the remaining covariance is attributed to noise (Langford et al., 2015) – the criteria used to extrapolate this assessment over an entire measurement period vary widely. Some illustrative examples are discussed below.

Loubet et al. (2022) computed an average random error following the recommendation of Langford et al. (2015), as the square root of the summed squared individual errors divided by the number of records. With this approach, the average random error decreases proportionally to when averaging over n measurements. Consequently, the longer the measurement period, the more likely a compound’s mean flux is to exceed its detection limit. Figure S15 compares the flux signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs, defined as the mean flux divided by the average error) reported in several PTR-ToF-MS studies for a subset of masses calibrated in the present study. For consistency, the SNRs shown for this work were computed using an average error calculated following Loubet et al. (2022). When averaging over our three measurement campaigns, the strong reduction in random error leads to SNRs that exceed those found in all other studies. In contrast, the lower SNRs in Park et al. (2013a), Ruuskanen et al. (2011), and Fischer et al. (2021) likely reflect the much shorter duration of their measurement periods. Applying the methodology of Loubet et al. (2022) to the present dataset would therefore lead to the conclusion that all 74 detected ions exhibit a mean flux significantly different from zero. This does however not necessarily imply that the exchange of a given VOC displays a clear, consistent, or interpretable temporal pattern.